Heart failure and cardiomyopathy

Page highlights:

How many Australians have heart failure?

- In 2017–18, an estimated 102,000 people aged 18 and over (0.5%) had heart failure.

- There were around 179,000 hospitalisations where heart failure or cardiomyopathy was recorded as the principal and/or additional diagnosis in 2020–21.

- The rate of heart failure or cardiomyopathy hospitalisations among Indigenous Australians was 2.9 times as high as the non-Indigenous rate.

Heart failure or cardiomyopathy was the underlying cause of 4,700 deaths in 2021 and was an associated cause in a further 21,300 deaths.

Heart failure or cardiomyopathy was the underlying cause of 4,700 deaths in 2021 and was an associated cause in a further 21,300 deaths.

What is heart failure and cardiomyopathy?

Heart failure occurs when the heart begins to function less effectively in pumping blood around the body. It can occur suddenly, although it usually develops slowly as the heart gradually becomes weaker.

Heart failure can result from a variety of diseases and conditions that impair or overload the heart. These include heart attack, high blood pressure, damaged heart valves or cardiomyopathy.

Cardiomyopathy is where the entire heart muscle, or a large part of it, is weakened. Causes of weakening include coronary heart disease, hypertension, viral infections and alcohol consumption above guideline levels. Cardiomyopathy and heart failure commonly occur together.

People with mild heart failure may have few symptoms, but in more severe cases it can result in chronic tiredness, reduced capacity for physical activity and shortness of breath. It often occurs as a comorbid condition with other chronic diseases, including CHD, diabetes and chronic kidney disease.

Generally, heart failure cannot be cured because the heart muscle has been irreversibly damaged, although some forms, caused by particular impairments such as heart valve defects or certain effects of a heart attack, may be cured if treated early enough. Treatment may improve quality of life, reduce hospital admissions and extend a person’s life. In certain end-stage patients, heart transplantation may be used.

How many Australians have heart failure?

Prevalence

An estimated 102,000 people aged 18 and over (0.5%) had heart failure in 2017–18, based on self-reported data from the ABS 2017–18 National Health Survey (ABS 2018).

Two-thirds of adults with heart failure (68,500 people) were aged 65 and over.

However, using self-reported data to estimate the number of people with heart failure underestimates the true burden, as the early stages of the disease are only mildly symptomatic, and a substantial proportion of cases are undiagnosed. A recent review of studies reported the prevalence of heart failure in the Australian population as ranging between 1.0% and 2.0% (Sahle et al. 2016).

Since heart failure and cardiomyopathy have a considerable impact on the health of Australians, estimates of prevalence based on self-report should be interpreted with caution.

Age and sex

An estimated 70,700 men and 40,200 women aged 18 and over had heart failure in 2017–18, based on self-reported data from the 2017–18 NHS (ABS 2018).

This corresponds to rates of 0.5% for men and 0.4% for women.

Hospitalisations

Heart failure and cardiomyopathy often occur alongside other chronic diseases, so both the principal and additional diagnoses of heart failure or cardiomyopathy should be counted when estimating their contribution to hospitalisations. As heart failure has historically been under recorded in hospital data and the accuracy of coding heart failure varies between Australian hospitals, it is likely that estimates are undercounts (Coory & Cornes 2005, Powell et al. 2000, Teng et al. 2008).

There were around 179,000 hospitalisations where heart failure or cardiomyopathy was recorded as the principal and/or additional diagnosis in 2020–21 – a rate of 697 per 100,000 population. This represents 1.5% of all hospitalisations in Australia in 2020–21.

Heart failure or cardiomyopathy was recorded as the principal diagnosis in 41% (73,300) of these hospitalisations.

In those cases where heart failure or cardiomyopathy was listed as an additional diagnosis, more than half (51%) had either a cardiovascular or respiratory disease listed as the principal diagnosis. The most common principal diagnoses in these cases were CHD (9.6% of hospitalisations), chronic lower respiratory diseases including bronchitis and chronic pulmonary obstructive disease (7.1%), influenza or pneumonia (6.6%) and atrial fibrillation or flutter (6.1%).

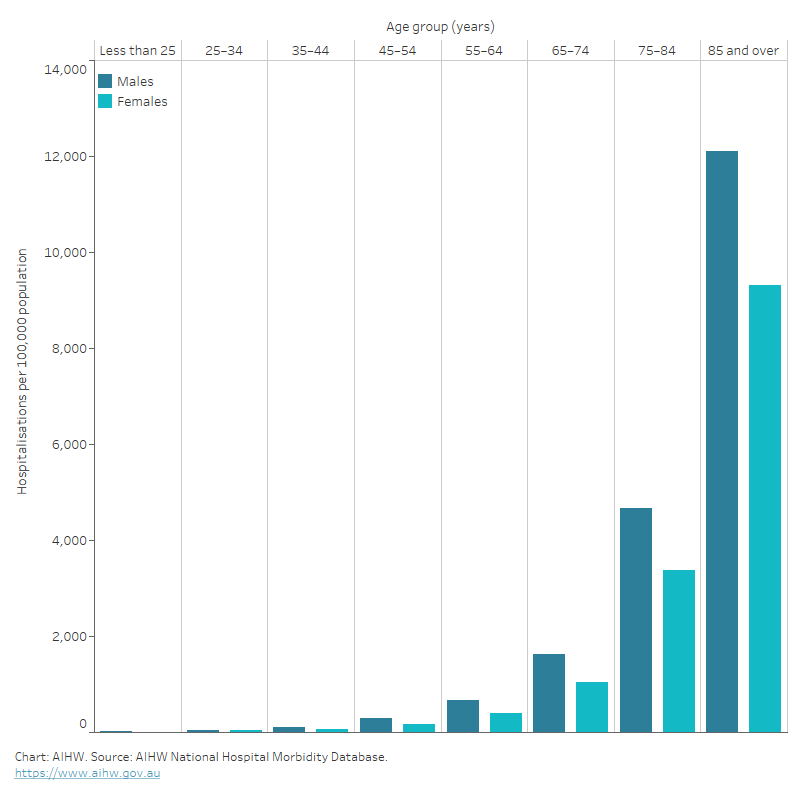

Age and sex

Where heart failure or cardiomyopathy was recorded as the principal and/or additional diagnosis, hospitalisation rates:

- were overall 1.5 times as high for males as females after adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations. Age-specific rates were higher among males than females in all age groups

- increased with age, with rates highest for males and females aged 85 and over – at least 2.5 times as high as those aged 75–84 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Heart failure and cardiomyopathy hospitalisation rates, principal and/or additional diagnosis, by age and sex, 2020–21

The bar chart shows that hospitalisation rates in 2020–21 for heart failure and cardiomyopathy as a principal and/or additional diagnosis were highest among men and women aged 85 and over (12,900 and 9,800 per 100,000 population, respectively).

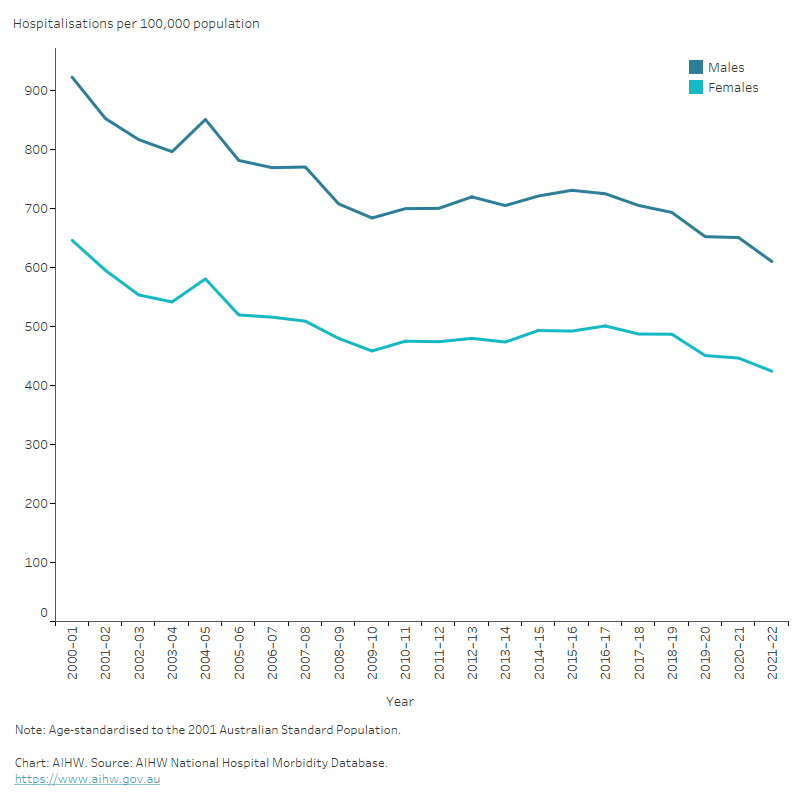

Trends

Between 2000–01 and 2020–21, there was a 29% reduction in the age-standardised rate of hospitalisations with a principal and/or additional diagnosis of heart failure or cardiomyopathy (767 to 541 per 100,000 population).

The number of heart failure and cardiomyopathy hospitalisations increased by 33% for males and 13% for females, while age-standardised rates fell by around 30% for both males and females (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Heart failure and cardiomyopathy hospitalisation rates, principal and/or additional diagnosis, by sex, 2000–01 to 2020–21

The line chart shows the decline in age-standardised heart failure and cardiomyopathy hospitalisation rates between 2000–01 and 2020–21 from 922 to 651 per 100,000 population for males and 646 to 447 per 100,000 population for females.

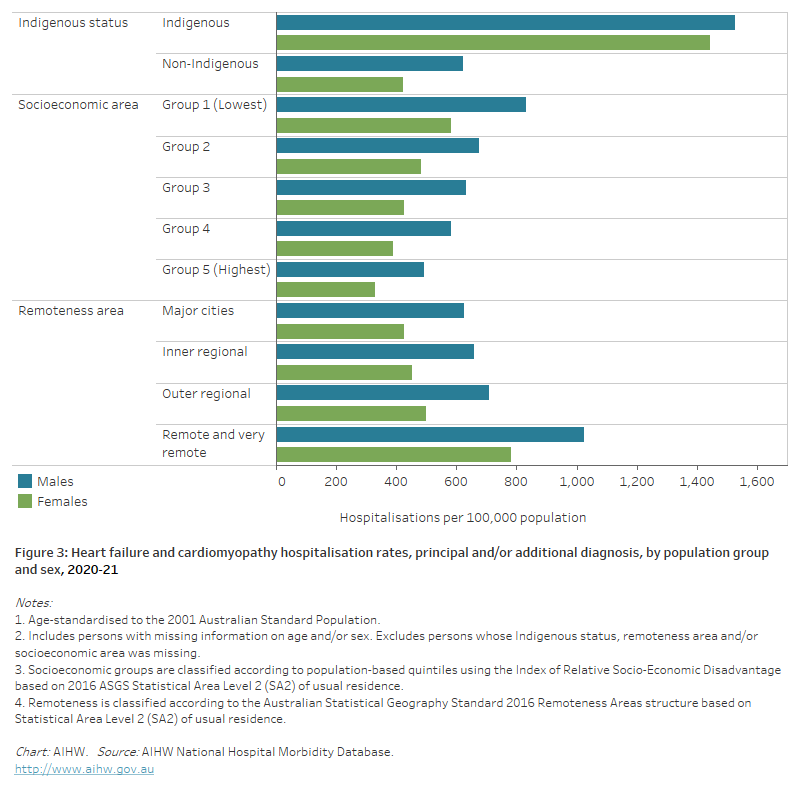

Variation among population groups

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

In 2020–21, there were around 6,800 hospitalisations with a principal and/or additional diagnosis of heart failure or cardiomyopathy among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, a rate of 785 per 100,000 population.

After adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations:

- the rate among Indigenous Australians was 2.9 times as high as the non-Indigenous rate

- the disparity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians was greater for females than males – 3.4 times as high for females and 2.4 times as high for males (Figure 3).

Socioeconomic area

In 2020–21, age-standardised heart failure and cardiomyopathy hospitalisation rates were 1.7 times as high for people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas compared with those in the highest socioeconomic areas.

The gap in hospitalisation rates between the lowest and highest socioeconomic areas was 1.7 times as high for males, and 1.8 times as high for females (Figure 3).

Remoteness area

In 2020–21, the age-standardised heart failure and cardiomyopathy hospitalisation rate for people living in Remote and very remote areas was 1.8 times as high as forMajor cities.

There were greater disparities in female rates (1.8 times as high) than male rates (1.6 times as high) (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Heart failure and cardiomyopathy hospitalisation rates, principal and/or additional diagnosis, by population group and sex, 2020–21

The horizontal bar chart shows that heart failure and cardiomyopathy hospitalisation rates were higher among Indigenous Australians, people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas and people living in Remote and very remote areas.

Deaths

Heart failure and cardiomyopathy contributed to 26,000 deaths (15% of all deaths) in 2021, at a rate of 101 per 100,000 population.

Heart failure or cardiomyopathy was the underlying cause of 4,700 deaths in 2021, and was an associated cause in a further 21,300 deaths.

Heart failure and cardiomyopathy are more likely to be listed as an associated cause of death. This is because it is often not heart failure or cardiomyopathy that leads directly to death – rather, one of their complications or comorbidities will be listed as the underlying cause of death on the death certificate.

When heart failure or cardiomyopathy are examined as an associated cause of death, the conditions most commonly listed as the underlying cause of death were:

- chronic ischaemic heart disease (15%)

- other chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (7.5%)

- acute myocardial infarction (5.8%)

- atrial fibrillation and flutter (5.1%)

- non-rheumatic aortic valve disorders (3.3%).

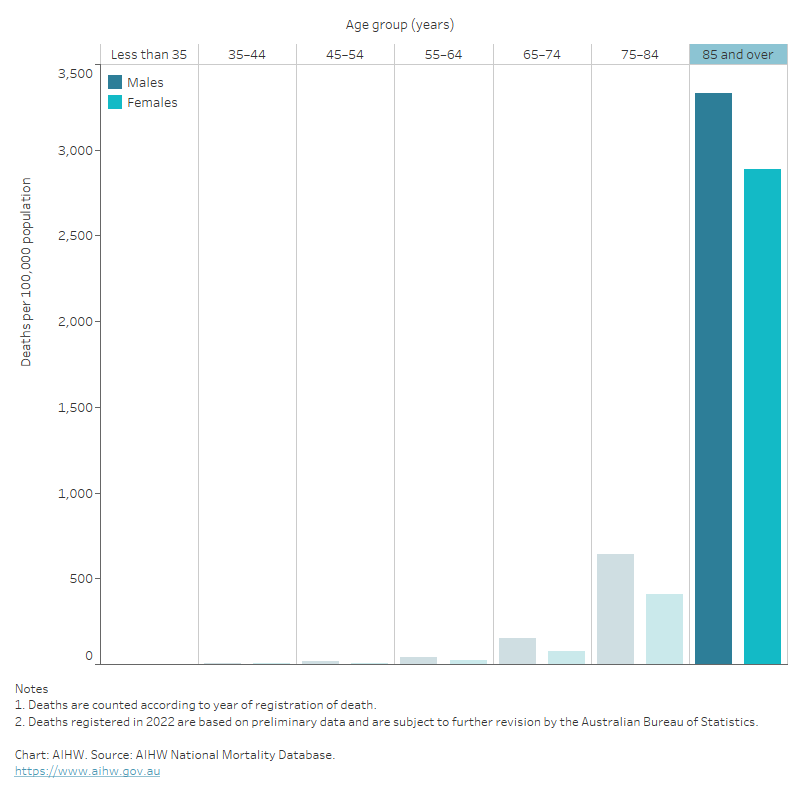

Age and sex

In 2021, death rates for heart failure and cardiomyopathy as the underlying or associated cause:

- were 1.4 times as high for males as for females , after adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations. Age-specific rates were higher for males than females across all age groups

- increased with age, with over 80% of deaths occurring among those aged 75 and over. Death rates for males and females were highest in the 85 and over age group – 5.3 times as high for males and 6.8 times as high for females aged 75–84 (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Heart failure and cardiomyopathy death rates, underlying or associated cause, by age and sex, 2021

The bar chart shows that heart failure and cardiomyopathy death rates in 2021 were highest among males and females 85 years and over (3,100 and 2,700 per 100,000 population, respectively).

Trends

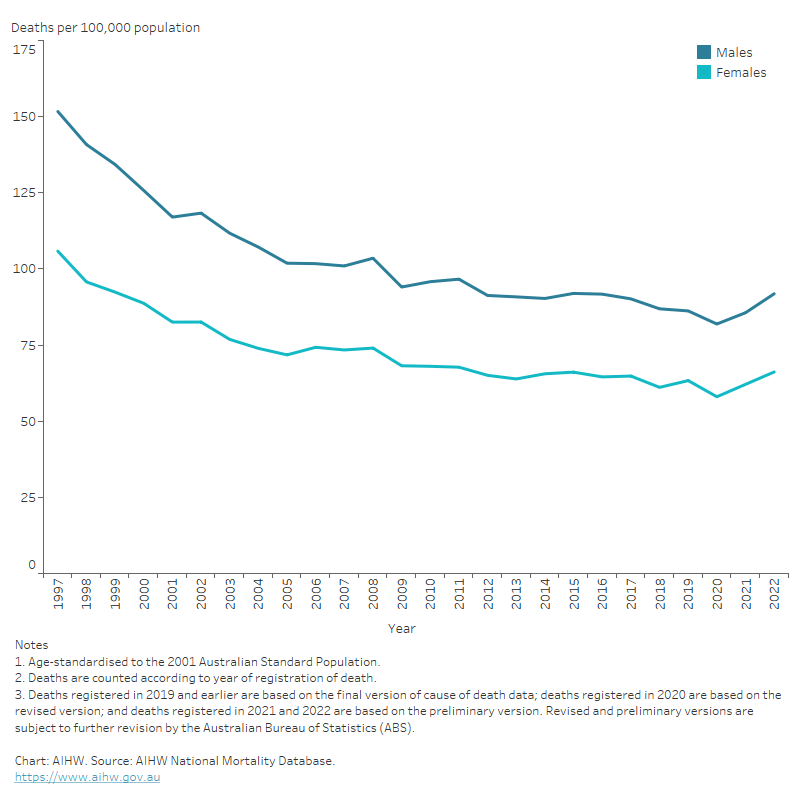

Between 1997 and 2021:

- the number of deaths where heart failure or cardiomyopathy was an underlying or associated cause increased by 25%, from 20,800 to 26,000

- age-standardised heart failure and cardiomyopathy death rates declined by more than 40% for both males and females (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Heart failure and cardiomyopathy death rates, underlying or associated cause, by sex, 1997–2021

The line chart shows the decline in age-standardised heart failure and cardiomyopathy death rates between 1997 and 2021 from 152 to 86 and 106 to 62 per 100,000 population for males and females, respectively.

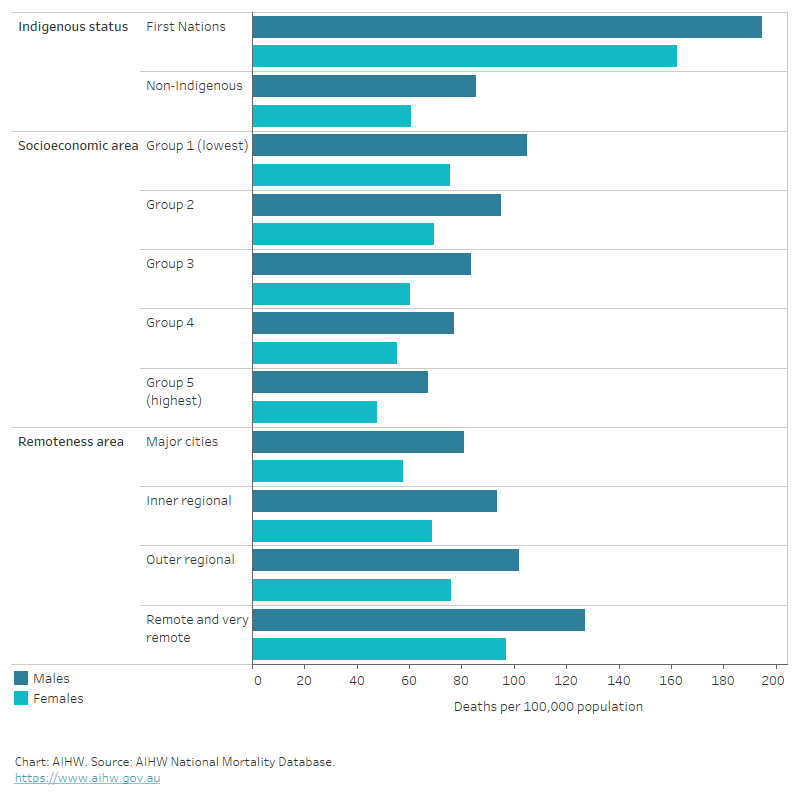

Variation among population groups

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

In 2019–2021, heart failure or cardiomyopathy was an underlying or associated cause of death for 1,400 Indigenous Australians in the jurisdictions with adequate Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander identification – a rate of 60 per 100,000 population.

The age-standardised Indigenous death rate was 2.3 times as high as the non-Indigenous rate. Indigenous males and females had heart failure and cardiomyopathy death rates 2.2 and 2.6 times as high as non-Indigenous males and females (Figure 6).

Socioeconomic area

In 2019–2021, the age-standardised death rate for heart failure or cardiomyopathy as an underlying or associated cause was 1.6 times as high for people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas compared with those living in the highest socioeconomic areas.

The disparity was similar for males and females (Figure 6).

Remoteness area

In 2019–2021, the age-standardised heart failure and cardiomyopathy death rate was 1.6 times as high for people living in Remote and very remote areas compared to those living in Major cities.

Males had higher heart failure and cardiomyopathy death rates than females in all remoteness areas (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Heart failure and cardiomyopathy death rates, underlying or associated cause, by population group and sex, 2019–2021

The horizontal bar chart shows that age-standardised heart failure and cardiomyopathy death rates in 2019–2021 were higher among Indigenous Australians, people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas and people living in Remote and very remote areas.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2018) National Health Survey: first results, 2017–18. ABS cat. no. 4364.0.55.001, AIHW, Australian Government.

Coory M & Cornes S (2005) Interstate comparisons of public hospital outputs using DRGs: Are they fair? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 29:143–8.

Powell H, Lim L, Heller R (2001) Accuracy of administrative data to assess comorbidity in patients with heart disease: an Australian perspective. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 54:P687–93.

Sahle BW, Owen AJ, Mutowo MP, Krum H, Reid CM (2016) Prevalence of heart failure in Australia: a systematic review. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders 16:32.

Teng TH, Finn J, Hung J, Geelhoed E, Hobbs M (2008) A validation study: how effective is the Hospital Morbidity Data as a surveillance tool for heart failure in Western Australia? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 32:405–7.