Clients exiting custodial arrangements

This section highlights findings in relation to clients who have recently exited custodial settings, including correctional facilities, youth justice detention centres and immigration detention centres (see Technical information for client definition). People who exit custodial settings are recognised as being at increased risk of homelessness; they are also less likely to exit homelessness [1]. The ability to secure stable housing may reduce the likelihood of reoffending [2].

Key findings in 2016–17

- In 2016–17, 8,118 people were identified as clients exiting from a custodial setting, an increase of 4% compared with 2015–16.

- Two-thirds of clients were exiting adult correctional facilities (65%).

- The majority of clients who exited custodial settings in 2016–17 were male (75%) and aged between 25 and 44 (60%).

- Two-thirds (66%) of clients were living alone when they sought assistance from specialist homelessness services (SHS), the highest rate of all SHS client groups.

- The majority of clients (64%) in 2016–17 had received homelessness services at some time in the previous 5 years.

Clients exiting custodial arrangements: 2012–13 to 2016–17

Since 2012–13, the number of people exiting custodial arrangements and seeking assistance from specialist homelessness services has been increasing. Key trends identified in this client population over the past 5 years are:

- The number of clients who recently exited custodial arrangements has grown on average 6% each year since 2012–13, and this annual growth rate is higher for females than males (10% compared with 5%).

- The proportion of clients receiving accommodation has declined from 41% in 2012–13 to 35% in 2016–17 (Table Exit Trends.1).

The proportion of clients achieving all case management goals was consistently lower than the general SHS population every year (see Tables Exit Trends.1 and Client Trends.1) and this group was one of the least likely to achieve all case management goals each year.

Table Exit Trends.1: Clients exiting custodial arrangements: at a glance—2012–13 to 2016–17

| 2012–13 | 2013–14 | 2014–15 | 2015–16 | 2016–17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of clients | 6,399 | 6,756 | 6,866 | 7,804 | 8,118 |

| Proportion of all clients | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Rate (per 10,000 population) | 2.8 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 3.3 | 3.4 |

| Housing situation at the beginning of first support period (proportion of all clients) | |||||

| Homeless | 36 | 27 | 31 | 31 | 32 |

| At risk of homelessness | 64 | 73 | 69 | 69 | 68 |

| Length of support (median number of days) | 46 | 53 | 45 | 44 | 45 |

| Average number of support periods per client | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| Proportion receiving accommodation | 41 | 40 | 41 | 38 | 35 |

| Median number of nights accommodated | 29 | 28 | 27 | 26 | 28 |

| Proportion of a client group with a case management plan | 58 | 53 | 50 | 52 | 53 |

| Achievement of all case management goals (per cent) | 10 | 11 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

Notes

- Rates are crude rates based on the Australian estimated resident population (ERP) at 30 June of the reference year. Minor adjustments in rates may occur between publications reflecting revision of the estimated resident population by the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- The denominator for the proportion achieving all case management goals is the number of client groups with a case management plan. Denominator values for proportions are provided in the relevant national supplementary table.

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection 2012–13 to 2016–17

Characteristics of clients exiting custodial arrangements 2016–17

Of the 8,118 clients exiting custodial arrangements in 2016–17:

- Two in 3 clients were returning clients (64%), that is, they had presented at a SHS agency at least once in the past 5 years.

- Over one-quarter of clients exiting custodial arrangements identified as Indigenous (27%), similar to the overall SHS population (25% Indigenous).

- Over 6,000 clients were male (75%), with the highest proportion of males being 35–44 years old (32%). The highest proportion of females was younger, 25–34 years (32%) (Supplementary table EXIT.1).

- Two-thirds of clients (66%) were living alone when they presented at a SHS agency.

- The main reason clients were seeking assistance was ‘transition from custodial arrangements’ (55%).

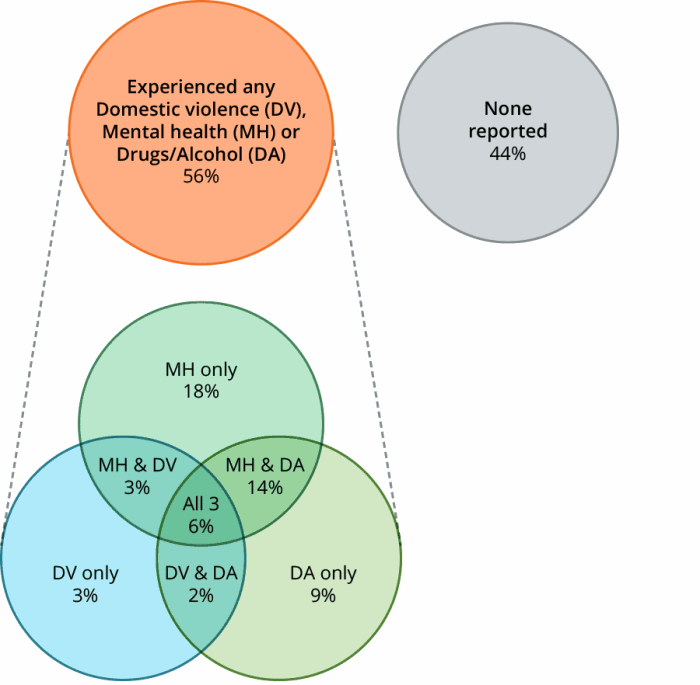

Many clients who are existing custodial arrangements face multiple challenges. Over half the clients (56%, or about 4,500 clients) exiting custodial arrangements reported additional vulnerabilities including domestic and family violence, a current mental health issue and/or problematic drug and/or alcohol use (Figure EXIT.1). The most common was mental health issues (42%, or about 3,400 clients) and of these clients about half also had problematic drug and/or alcohol use. That is:

- 14% were experiencing both mental health and problematic drug and/or alcohol use

- a further 6% (over 500 clients) were experiencing all three vulnerabilities (mental health, problematic drug and/or alcohol use, and domestic and family violence).

Figure EXIT.1: Clients exiting custodial arrangements, by selected vulnerability characteristics, 2016-17

Notes

- Client vulnerability groups are mutually exclusive.

- Clients are aged 10 and over.

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection 2016–17.

Services needed and provided

Around 5,300 clients exiting custodial arrangements needed assistance with accommodation (66%). Of these clients, 54% were provided with assistance.

- For clients needing short-term or emergency housing (47%, or nearly 4,000), 6 in 10 (60%) were provided with assistance.

- Of the 3,000 clients (37%) exiting custodial arrangements needing assistance to sustain tenancy or prevent tenancy failure or eviction, 83% received this assistance.

Certain services were requested by clients exiting custodial arrangements more frequently than by the overall SHS population. Some of these include:

- Assistance with challenging social and behavioural problems (19% compared with 13%).

- Drug/alcohol counselling (11% compared with the 4% of the overall SHS population).

- Mental health services (10% compared with 8%).

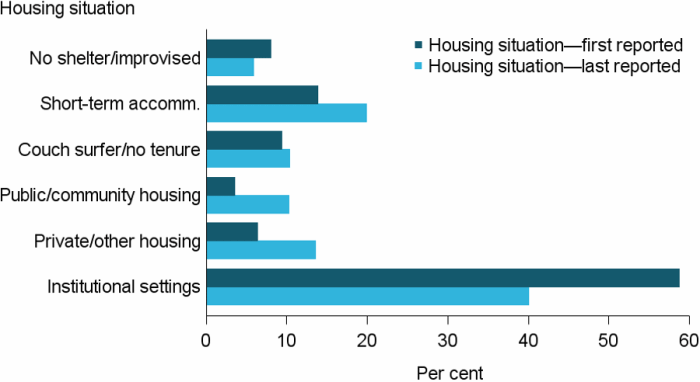

Housing outcomes

At the beginning of support, the majority of clients exiting custodial settings were living in institutions (59%), short-term or emergency accommodation (14%) or living in a house, townhouse or flat with no tenure, known as ‘couch surfing’ (9%) (Supplementary table EXIT.4).

- The proportion of clients who reported living in institutional settings decreased to 40% following support (Figure EXIT.2).

- One in 5 clients (20%) were housed in short-term temporary accommodation at the end of support, up from 14% at the beginning of support.

- The proportion of clients living in private or other housing (as a renter, rent free or owner) more than doubled from the beginning of support (6%) to the end of support (14%).

Figure EXIT.2: Clients exiting custodial arrangements, by housing situation at beginning of support and end of support, 2016–17

Notes

- The SHSC classifies clients living with no shelter or improvised/inadequate dwelling, short-term temporary accommodation, or in a house, townhouse, or flat with relatives (rent free) as homeless. Clients living in public or community housing (renter or rent free), private or other housing (renter or rent free), or in institutional settings are classified as housed.

- No shelter/improvised includes inadequate dwellings; short-term accommodation includes temporary and emergency accommodation; couch surfer/no tenure includes living in a house, townhouse or flat with relatives rent free; public/community housing includes both renting or rent free; and private/other housing includes both renting or rent free.

- Proportions include only clients with closed support at the end of the reporting period.

Source: Specialist homelessness services 2016–17, National supplementary table EXIT.4.

At the start of support the majority of clients exiting custodial arrangements were at risk of homelessness (69%, or about 4,100 clients), and most of these were in institutions (59%). This may be explained by prisoners receiving SHS assistance prior to their release (clients housed in institutional settings are classified in the at risk population).

Of those exiting custodial arrangements who were housed but at risk of homelessness when they began support:

- Overall 77% were in stable housing at the end of support (see Glossary) (Table EXIT.2), mostly in institutional settings (about 2,000).

- Agencies were able to assist 3 in 4 clients (74%, or 146 clients) living in public or community housing to maintain this tenancy and assist a further 7% into private or other housing at the end of support.

- Agencies also assisted those living in private or other housing to maintain their tenancy, with 69% (or 237 clients) still in private or other housing and a further 9% in public or community housing at the end of support.

Of those clients exiting custodial arrangements who were homeless when they began SHS support:

- 33% (or 539 clients) were assisted into stable housing at the end of support; 67% were homeless.

- Agencies were best able to assist those living in short-term or emergency accommodation into stable housing (39%) with 16% assisted into private/other housing and 13% assisted into public or community housing.

Table EXIT.2: Clients exiting custodial arrangements, housing situation at beginning and end of support, 2016–17 (per cent)

| Situation at beginning of support | Situation at end of support: homeless |

Situation at end of support: housed |

|---|---|---|

| Homeless | 66.6 | 33.4 |

| At risk of homelessness | 22.5 | 77.5 |

Notes

- The SHSC classifies clients living with no shelter or improvised/ inadequate dwelling, short-term temporary accommodation, or in a house, townhouse, or flat with relatives (rent free) as homeless. Clients living in public or community housing (renter or rent free), private or other housing (renter or rent free), or in institutional settings are classified as housed.

- Proportions include only clients with closed support at the end of the reporting period. Per cent calculations are based on total clients, excluding ‘Not stated/other’.

Source: Specialist homelessness services 2016–17, National supplementary table EXIT.4.

References

- Johnson, G., Scutella, R., Tseng, Y., Wood, G. (2015) Entries and exits from homelessness: a dynamic analysis of the relationship between structural conditions and individual characteristics, AHURI Final Report No. 248, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, Melbourne, https://www.ahuri.edu.au/research/final-reports/248.

- Australian Government 2008. The road home: a national approach to reducing homelessness. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.