Drowning and submersion

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) Drowning and submersion, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 27 July 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023). Drowning and submersion. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/injury/drowning-and-submersion

MLA

Drowning and submersion. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 06 July 2023, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/injury/drowning-and-submersion

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Drowning and submersion [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023 [cited 2024 Jul. 27]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/injury/drowning-and-submersion

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2023, Drowning and submersion, viewed 27 July 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/injury/drowning-and-submersion

This article is part of Injury in Australia

These articles each focus on a major cause of injury resulting in hospitalisation or death in Australia.

Injuries can be classified by cause once hospital staff or coroners discover how the person was injured. In some cases they are not sure if it was accidental or deliberate, in which case the record will show undetermined intent.

Each cause will be updated periodically throughout the year.

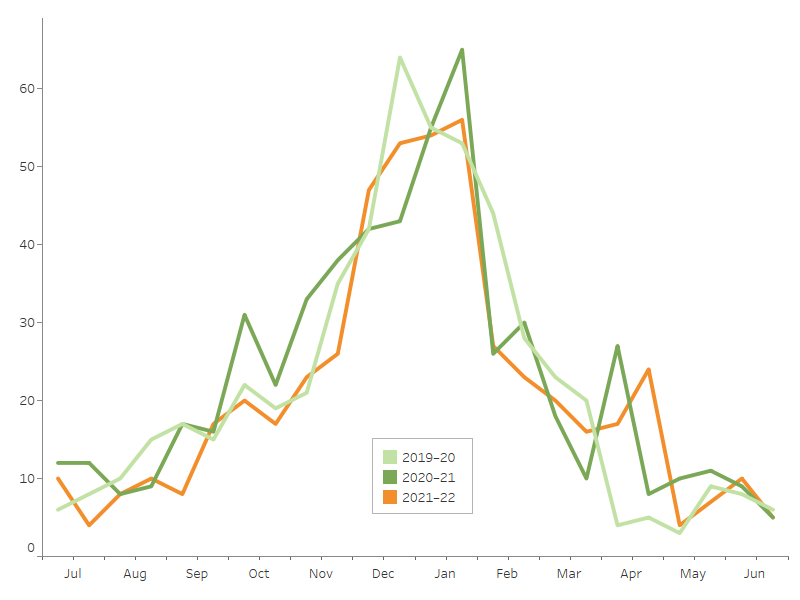

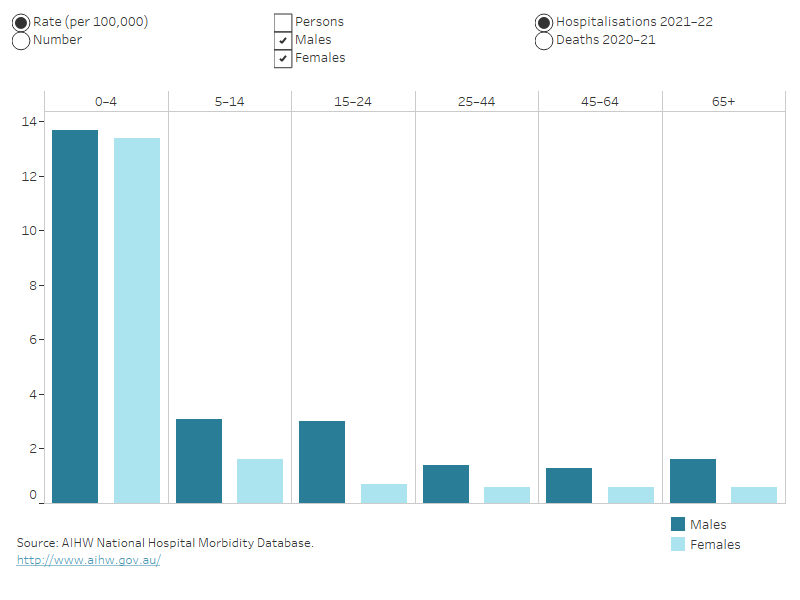

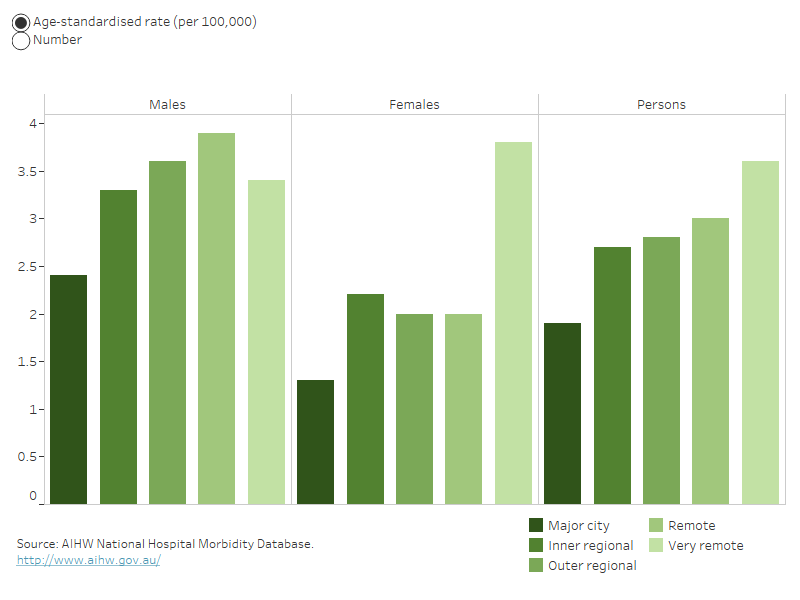

520 hospitalisations in 2021–22

520 hospitalisations in 2021–22 270 deaths in 2020–21

270 deaths in 2020–21