For more detail, see Data tables A1–3 and D1–3.

There are many ways that the severity, or seriousness, of an injury can be measured. Some of the ways to measure the severity of hospitalised injuries are:

- number of days in hospital

- time in an intensive care unit (ICU)

- time on a ventilator

- in-hospital deaths.

The average number of days in hospital, and the rate of in-hospital deaths for accidental poisoning were lower than the average for all injury hospitalisations, but the percentage of cases that included either time in an ICU or on continuous ventilatory support were higher (Table 4).

Table 4: Severity of accidental poisoning hospitalisation cases, 2021–22| | Accidental poisoning | All injuries |

|---|

Average number of days in hospital | 2.6 | 4.7 |

% of cases with time in an ICU | 8.1 | 2.0 |

% of cases involving continuous ventilatory support | 5.9 | 1.1 |

In-hospital deaths (per 1,000 cases) | 3.5 | 5.9 |

Note: Average number of days in hospital (length of stay) includes admissions that are transfers from 1 hospital to another or transfers from 1 admitted care type to another within the same hospital, except where care involves rehabilitation procedures.

Source: AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database.

For more detail, see Data tables A12–13.

Among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people:

- there were 794 hospitalisations in 2021–22 due to accidental poisoning (Table 5)

- the hospitalisation rate for males was 1.1 times as high as for females

- hospitalisation rates were highest for children aged 0–4

- there were 77 deaths due to accidental poisoning in 2020–21 (Table 6)

- the rate of death for males was 1.3 times as high as for females

Table 5: Accidental poisoning hospitalisation by sex, Indigenous Australians, 2021–22 | Males | Females | Persons |

|---|

Number | 413 | 381 | 794 |

Rate (per 100,000) | 94 | 87 | 90 |

Note: Persons includes cases where sex is intersex, indeterminate or missing.

Source: AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database.

Table 6: Accidental poisoning death by sex, Indigenous Australians, 2020–21 | Males | Females | Persons |

|---|

Number | 44 | 33 | 77 |

Rate (per 100,000) | 12 | 8.7 | 10 |

Notes

- Rates are crude per 100,000 population.

- Deaths data only includes data for New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and the Northern Territory.

Source: AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database.

For more detail, see Data tables A4–5 and D4-5.

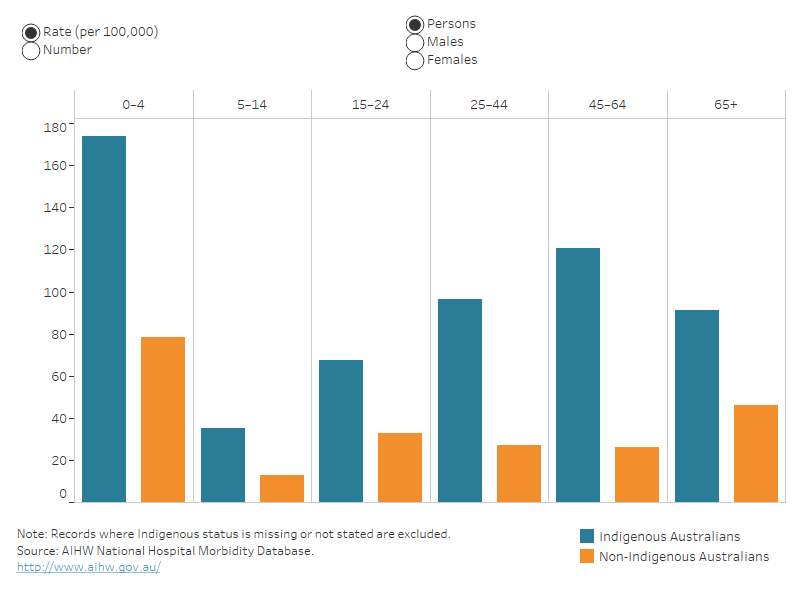

Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians, compared with non-Indigenous Australians, after adjusting for differences in population age structure, were:

- 3.1 times as likely to be hospitalised due to accidental poisoning in 2021–22 (Table 7)

- 3.0 times as likely to die because of accidental poisoning in 2020–21 (Table 8).

Table 7: Age-standardised rates of accidental poisoning hospitalisation (per 100,000) by Indigenous status and sex, 2021–22 | Males | Females | Persons |

|---|

Indigenous Australians | 101 | 91 | 96 |

Non-Indigenous Australians | 34 | 29 | 31 |

Notes

- Rates are age-standardised to the 2001 Australian population (per 100,000).

- ‘Non-Indigenous Australians’ excludes cases where Indigenous status is missing or not stated.

Source: AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database.

Table 8: Age-standardised rates of accidental poisoning death (per 100,000) by Indigenous status and sex, 2020–21 | Males | Females | Persons |

|---|

Indigenous Australians | 16 | 12 | 14.2 |

Non-Indigenous Australians | 7.0 | 2.7 | 4.8 |

Notes

- Rates are age-standardised to the 2001 Australian population (per 100,000).

- ‘Non-Indigenous Australians’ excludes cases where Indigenous status is missing or not stated.

- Deaths data only includes data for New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and the Northern Territory.

Source: AIHW National Mortality Database.

For more detail, see Data tables A6 and D8.

The rate of hospitalisation for accidental poisoning was highest among the 0–4 life-stage age group for both Indigenous and other Australians (Figure 4).

Deaths data are not presented here because of small numbers.

8,800 hospitalisations in 2021–22

8,800 hospitalisations in 2021–22 1,400 deaths in 2020–21

1,400 deaths in 2020–21