For more detail, see Data tables A1–3 and D1–3.

There are many ways that the severity, or seriousness, of an injury can be assessed. Four measures of the severity of hospitalised injuries are:

- number of days in hospital

- time in an intensive care unit (ICU)

- time on a ventilator

- in-hospital deaths.

While the average number of days in hospital for intentional self-harm was lower than that for all hospitalised injuries, the percentages of self-harm cases that included time in an ICU or on continuous ventilatory support were the highest of all the main causes of hospitalised injuries. The rate of in-hospital deaths was higher than for all injuries (Table 3).

Table 3: Severity of intentional self-harm hospitalisations, 2021–22

| |

Intentional self-harm

|

All injuries

|

|

Average number of days in hospital

|

3.1

|

4.7

|

|

% of cases with time in an ICU

|

10.0

|

2.0

|

|

% of cases involving continuous ventilatory support

|

7.9

|

1.1

|

|

In-hospital deaths (per 1,000 cases)

|

7.0

|

5.9

|

Note: Average number of days in hospital (length of stay) includes admissions that are transfers from 1 hospital to another or transfers from 1 admitted care type to another within the same hospital, except where care involves rehabilitation procedures.

Source: AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database.

For more detail, see Data tables A13–15.

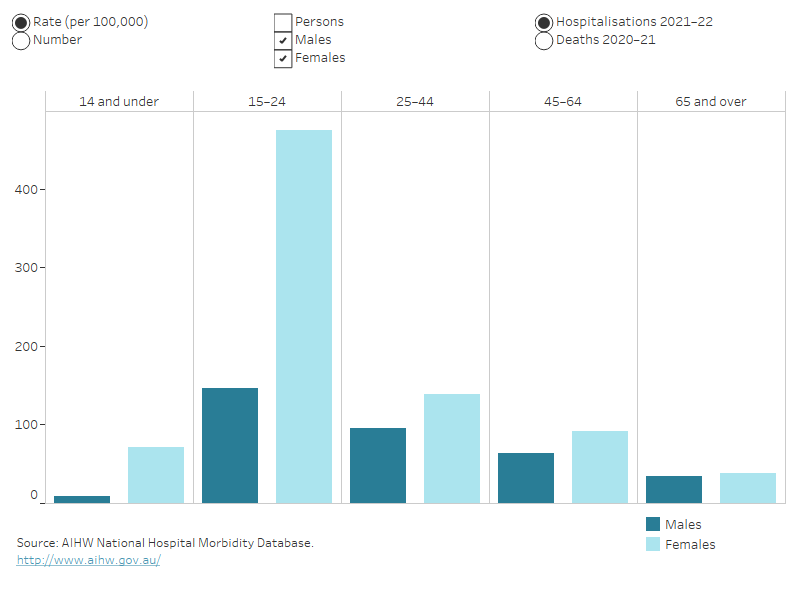

Among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people:

- there were 2,800 hospitalisations due to intentional self-harm in 2021–22 (Table 4)

- females were 1.6 times as likely as males to be hospitalised due to intentional self-harm

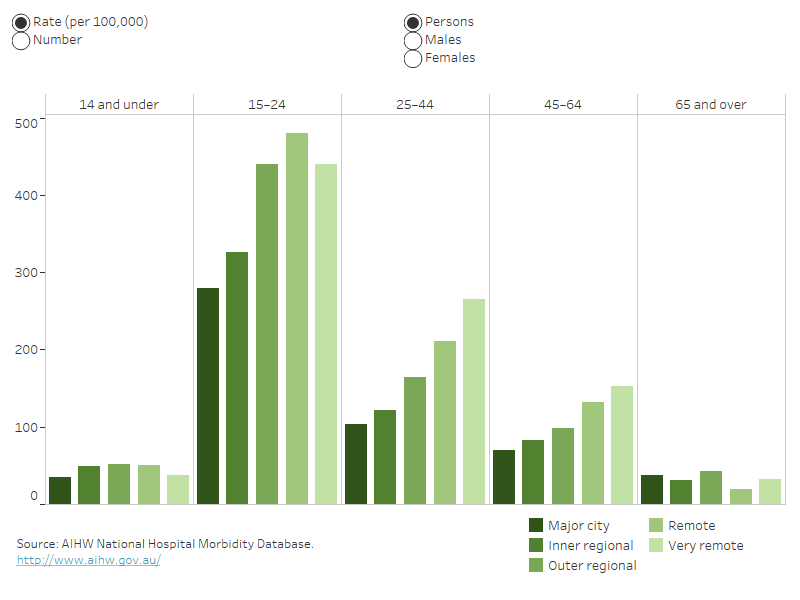

- intentional self-harm hospitalisation rates were highest in the 15–24 age group (Figure 3)

- there were 179 deaths by suicide in 2020–21 (Table 5)

- males were 2.7 times as likely as females to die by suicide.

Table 4: Hospitalisations for intentional self-harm by sex, Indigenous Australians, 2021–22

|

|

Males

|

Females

|

Persons

|

|

Number

|

1,020

|

1,804

|

2,829

|

|

Rate (per 100,000)

|

232

|

410

|

322

|

Note: Rates are crude per 100,000 population.

Source: AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database.

Table 5: Deaths by suicide by sex, Indigenous Australians, 2020–21

|

|

Males

|

Females

|

Persons

|

|

Number

|

131

|

48

|

179

|

|

Rate (per 100,000)

|

35

|

13

|

24

|

Notes:

- Rates are crude per 100,000 population.

- Deaths data only includes data for New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and the Northern Territory.

Source: AIHW National Mortality Database.

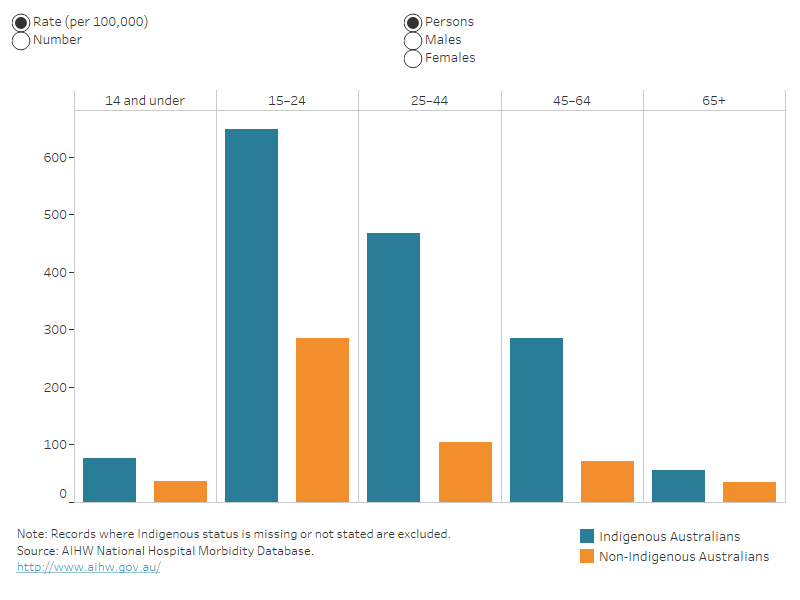

Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians, compared with non-Indigenous Australians (after adjusting for the difference in population age structure), were:

- 3.2 times as likely to be hospitalised due to intentional self-harm in 2021–22 (Table 6 and Figure 3)

- 2.7 times as likely to die by suicide in 2020–21 (Table 7).

Table 6: Age-standardised rates of hospitalisation (per 100,000) for intentional self-harm by Indigenous status and sex, 2021–22

|

|

Males

|

Females

|

Persons

|

|

Indigenous Australians

|

247

|

392

|

319

|

|

Non-Indigenous Australians

|

63

|

138

|

100

|

Notes

- Rates are age-standardised to the 2001 Australian population (per 100,000).

- ‘Non-Indigenous Australians’ excludes cases where Indigenous status is missing or not stated.

Source: AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database.

Table 7: Age-standardised rates of suicide death (per 100,000) by Indigenous status and sex, 2020–21

|

|

Males

|

Females

|

Persons

|

|

Indigenous Australians

|

38

|

13

|

25

|

|

Non-Indigenous Australians

|

18.2

|

5.7

|

11.9

|

Notes

- Rates are age-standardised to the 2001 Australian population (per 100,000).

- ‘Non-Indigenous Australians’ excludes cases where Indigenous status is missing or not stated.

- Deaths data only includes data for New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and the Northern Territory.

Source: AIHW National Mortality Database.

The rate of hospitalisations for intentional-self harm was highest among the 15–24 life-stage age group for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians (Figure 4). Deaths data are not presented because of small numbers.

26,400

26,400 3,100

3,100