This represents 3.8% of injury hospitalisations and 1.6% of injury deaths.

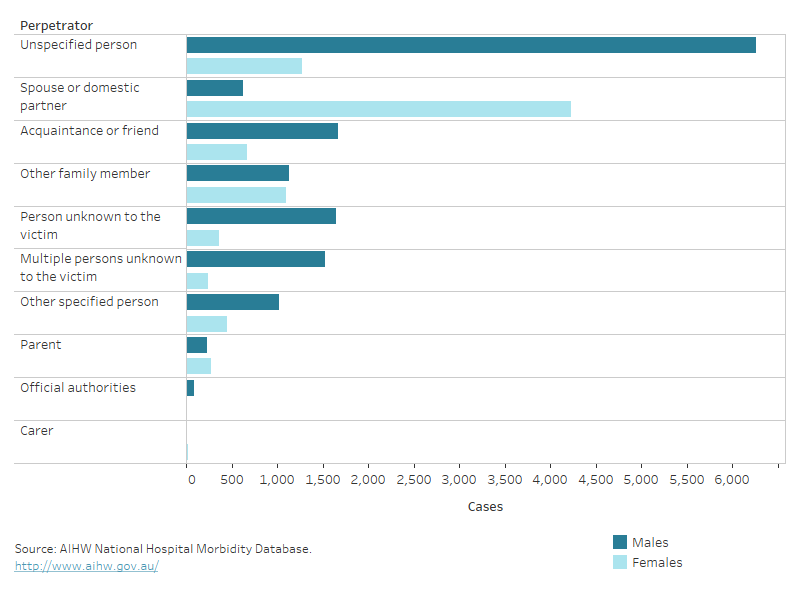

People who seek health care following an assault might choose not to disclose the cause of their injuries. This could be because they know the perpetrator and want to avoid criminal proceedings. For this reason, assault injuries are probably not all identified as such in hospital statistics – they might instead be coded as an unintentional injury such as a Falls or Contact with an object – or details of the assault may be incomplete or unspecified. For more information, see the technical notes.

For those hospitalised with multiple injuries, we have focused on the main, or ‘principal’ injury that led to the hospitalisation.

Causes of injury in assault hospitalisations

Of the injuries in those hospitalised for assault in 2021–22:

- 59% were caused by bodily force

- 14% were caused by a blunt object (Table 1).

Table 1: Causes of injury in assault hospitalisations, 2021–22Cause | Number | % | Rate

(per 100,000) |

|---|

Bodily force (includes sexual assault) (Y04–05) | 11,867 | 59 | 46.2 |

|---|

Blunt object (Y00) | 2,768 | 14 | 10.8 |

|---|

Sharp object (X99) | 2,627 | 13 | 10.2 |

|---|

Other or unspecified (X85–93, X95–98, Y01–03, Y06–09, Y35–36) | 2,938 | 15 | 11.4 |

|---|

Total | 20,200 | 100 | 78.6 |

|---|

Notes

- Rates are crude per 100,000 population, calculated using estimated resident population as at 31 December of the relevant year.

- Percentages may not total 100 due to rounding.

- Codes in brackets refer to the ICD-10-AM (11th edition) external cause codes (ACCD 2019).

Source: AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database.

Causes of injury in homicide deaths

In 2020–21, the most common cause of homicide deaths was a sharp object such as a knife (38%) (Table 2).

Table 2: Causes of injury in homicide deaths, 2020–21Cause | Number | % | Rate

(per 100,000) |

|---|

Sharp object (X99) | 82 | 38 | 0.3 |

|---|

Bodily force (includes assault and sexual assault) (Y04–05) | 47 | 22 | 0.2 |

|---|

Assault by firearm discharge or explosive material (X93–X96) | 24 | 11 | 0.1 |

|---|

Other or unspecified (X85–93, X95–98, Y01–03, Y06–09, Y35–36) | 65 | 30 | 0.2 |

|---|

Total | 218 | 100 | 0.8 |

|---|

Notes

- Rates are crude per 100,000 population.

- Percentages may not total 100 due to rounding.

- Codes in brackets refer to the ICD-10 external cause codes (WHO 2011).

Source: AIHW National Mortality Database.

Trends over time

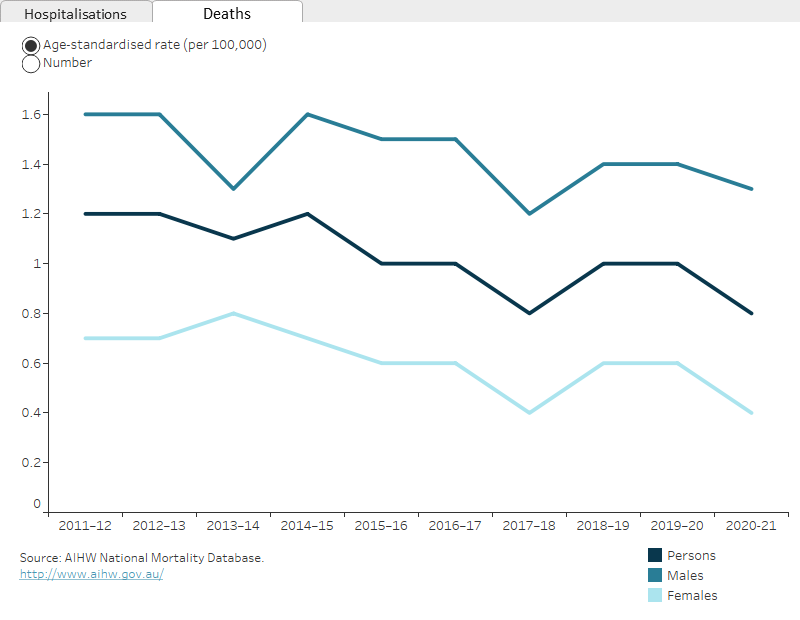

Over the period from 2017–18 to 2021–22, the age-standardised rate of hospitalisations due to assault declined by an annual average of 2.8%.

From 2012–13 to 2016–17 there was an annual average decline of 0.2% per year for the period from 2011–12 to 2016–17.

Figure 1 shows that, when examined by sex, the decreases are mostly accounted for in the rate for males.

There is a break in the time series for hospitalisations between 2016–17 and 2017–18 due to a change in data collection methods (see the technical notes for details).

The homicide rate showed an average annual decrease of 3.7% between 2011–12 and 2020–21. There were notable fluctuations, however, over this period. (Figure 1).