New (and emerging) psychoactive substances

Key findings

View the new (and emerging) psychoactive substances in Australia fact sheet >

New (and emerging) psychoactive substances (NPS) may be defined as substances, whether in a pure form or preparation, where most are not controlled by international drug control conventions, but which may pose a public health threat (UNODC 2022). NPS often mimic the effects of existing illicit substances (UNODC 2022). There are several main types of NPS, including:

- Synthetic cannabinoids – designed to mimic or produce similar effects to cannabis.

- Phenethylamines – a class of drugs with psychoactive and stimulant effects and includes amphetamine, methamphetamine and MDMA (ecstasy). NPS phenethylamines include the ‘2C series’, the NBOMe series, PMMA and benzodifurans.

- Tryptamines – psychoactive hallucinogens found in plants, fungi and animals.

- Piperazines – typically described as ‘failed pharmaceuticals’ and are frequently sold as ecstasy due to their central nervous system stimulant properties.

- Synthetic cathinones – have an amphetamine-type analogue including mephedrone (‘meow meow’) and methylone.

- Novel benzodiazepines – often do not belong to a precise category and are grouped into “other substances”. They have sedative and hypnotic effects, varying dosages of active ingredients and contain contaminants, including highly potent synthetic opioids (UNODC 2022).

- Other names given to this group of drugs include research chemicals, analogues, legal highs, herbal highs, bath salts, novel psychoactive substances and synthetic drugs (NDARC 2016).

Availability

From 2009–2021, NPS have been reported in 134 countries and territories in all regions of the world. Over 1,100 substances have been reported to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) Early Warning Advisory, by Governments, laboratories and partner organisations (UNODC 2022).

The number of NPS found globally has been stabilising in recent years – 548 substances in 2020, with 77 of these newly identified psychoactive substances; a year later the number of NPS identified for the first time fell to 50 (UNODC 2022).

In Australia, the NPS market is highly dynamic with fluctuations in the types of NPS available (Sutherland et al. 2020).

The Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission (ACIC) collects national illicit drug seizure data annually from federal, state and territory police services, including the number and weight of seizures to inform the Illicit Drug Data Report (IDDR). According to the latest IDDR:

- An increase of 113% in the number of NPS border detections, from 609 in 2019–20 to 1,299 in 2020–21.

- By number, tryptamine-type substances, and other NPS each accounted for 40% of analysed NPS seizures, while cathinone-type substances accounted for the remaining 20% of total analysed seizures made and examined by the Australian Federal Police.

- By weight, other NPS accounted for 92% of the weight of analysed NPS seizures in 2020–21 (ACIC 2023).

There were no seizures of synthetic cannabinoids or amphetamine-type substances in 2020–21.

Consumption

Synthetic cannabinoids

The use of synthetic cannabinoids in Australia is low.

- The 2022–2023 National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS) showed that although lifetime use of synthetic cannabinoids doubled between 2013 and 2022–2023 (from 1.3% to 2.6%), recent use dropped dramatically from 1.2% to *0.1% (AIHW 2024, tables 5.2 and 5.6).

- People who regularly use ecstasy and other stimulants interviewed as part of the Ecstasy and Related Drugs Reporting System (EDRS) reported infrequent use of synthetic cannabinoids in 2023, with less than 1% of the sample reporting use in the past 6 months (Sutherland et al. 2023).

- The low reported use of synthetic cannabinoids has been attributed to the fact that these synthetic cannabinoids do not produce the kinds of effects that people are seeking.

- The National Wastewater Drug Monitoring Program (NWDMP) ceased monitoring the synthetic cannabinoids JWH-018 and JWH-073 from October 2017. These NPS had not been detected since monitoring commenced in August 2016 (ACIC 2018).

* Estimate has a relative standard error of 25% to 50% and should be used with caution.

Other NPS

The use of other NPS among the general population in Australia is similarly low, however the use of some NPS has risen in recent years.

- The 2022–2023 NDSHS showed that between 2019 and 2022–2023 the lifetime use of other psychoactive substances remained stable (from 0.7% to 0.8%) (AIHW 2024, Table 5.104; Figure NPS1). In the last 12 months, less than *0.1% of people aged over 14 had used other psychoactive substances.

- Methylone and mephedrone (synthetic stimulants) were previously included in the National Wastewater Drug Monitoring Program (NWDMP) as examples of NPS. However, due to low levels of detection, they were replaced by ketamine from December 2020.

*The estimate for recent use of other psychoactive substances has a relative standard error of 25% to 50% and should be used with caution.

In 2021, the EDRS changed reporting of NPS to allow for comparability across different reporting methods. From 2021, the EDRS will report recent 6 month use of any NPS as ‘including plant based NPS’ and ‘excluding plant based NPS’.

In 2023, EDRS participants reporting recent 6-month use of:

- Any NPS, including plant-based, remained unchanged from 2022 (11%). This is the lowest percentage of participants reported since monitoring started (Sutherland et al. 2023, Table 16).

- Any NPS, excluding plant-based, remained unchanged from 2022 (9%) (Sutherland et al. 2023, Table 17).

Hallucinogens

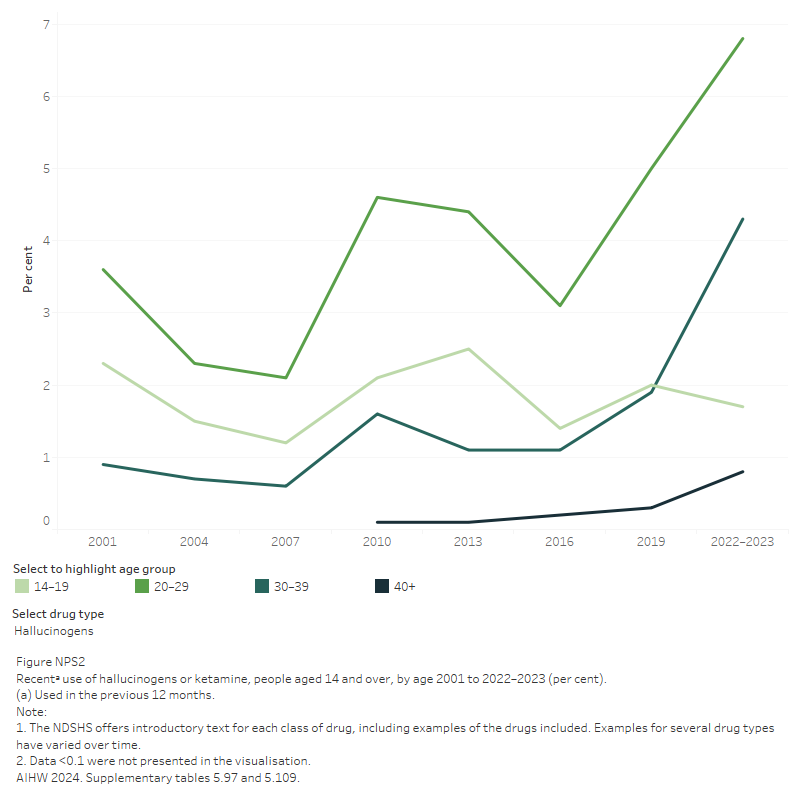

Recent use of hallucinogens among people aged 14 and over has gradually increased since 2007 (AIHW 2024). According to the 2022–2023 NDSHS:

- 2.4% of people aged 14 and over had used hallucinogens in the last 12 months, up from 1.6% in 2019.

- 12.2% reported lifetime use, up from 10.4% in 2019.

- Recent hallucinogen use was most common among people aged 20–29 (6.8%) (Figure NPS 1; AIHW 2024, Table 5.97).

- For people who had recently used hallucinogens, 77% had used mushrooms/psilocybin (1.8% of total population aged 14 and over) and 62% had used LSD/acid/tabs (1.5%) (AIHW 2024, tables 5.98 and 5.99).

Ketamine

Ketamine is a dissociative drug originally used as an anaesthetic for medical purposes (NDARC 2021). In recent years, recreational use of ketamine has increased (AIHW 2024). Data from the 2022–2023 NDSHS showed that

- 1.4% of people aged 14 and over had used ketamine in the last 12 months, up from 0.9% in 2019 and 0.4% in 2016 (AIHW 2024, Table 5.6).

- 4.3% of people aged 14 and over had used ketamine in their lifetime, up from 3.1% in 2019 (Figure NPS 1; AIHW 2024, Table 5.2)

- Ketamine use was highest among people aged 20–29 years (4.2%) (Figure NPS 1; AIHW 2024, Table 5.109).

The 2023 EDRS showed that of people who consumed ecstasy or illicit stimulants, 49% had used ketamine in the previous 6 months. This remained unchanged from 2022 (49%) (Sutherland et al 2023).

Figure NPS 1: Recentᵃ use of hallucinogens or ketamine, people aged 14 and over, by age 2004 to 2022–2023 (per cent)

This line graph shows that between 2019 and 2022-2023, ketamine use has increased across all age groups between 15 and 39 years and the use of hallucinogens has increased among people aged 20 to 39.

The amount of ketamine consumed cannot be determined based on excreted concentrations in wastewater, therefore ketamine is reported in the NWDMP as the amount excreted (in mg) into the sewer network per 1,000 people per day. The amount of ketamine excretion is relatively low, but has fluctuated since its introduction to the NWDMP program in December 2020. According to the 2021 NWDMP, between April and August 2023:

- Ketamine excretion in both capital cities and regional sites decreased.

- Higher levels of excretion were reported in capital city sites than regional sites (ACIC 2024)

Harms

NPS comprises a category of substances that are fast-evolving, often diversified and typically volatile and may pose a threat to public health (UNODC 2022).

The use of NPS has been linked to health problems, including (but not limited to):

- cardiovascular problems

- memory and cognitive impairment

- psychiatric problems

- aggression and acute psychosis

- breathing difficulties

- fatigue

- headaches

- nausea and persistent vomiting

- abnormally fast heartbeat (tachycardia)

- seizures

- tolerance and dependence (ACIC 2019; NSW Ministry of Health 2017; UNODC 2024).

Policy context

The laws surrounding NPS are complex and vary between Australian jurisdictions.

- To deal with the rapid growth of NPS, some Australian jurisdictions such as New South Wales have implemented blanket bans on selling any substance that has a psychoactive effect (exempting alcohol, tobacco and food).

- In other jurisdictions, such as Western Australia, specific NPS are banned with additional substances regularly added to the list.

- Commonwealth legislation also bans any psychoactive substance not covered by legislation elsewhere (NDARC 2016).

ACIC (Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission) (2018) National Wastewater Drug Monitoring Program Report 4. Canberra: ACIC, accessed 30 August 2021.

ACIC (2019) Illicit Drug Data Report 2017–18. Canberra: ACIC, accessed 7 August 2019.

ACIC (2023) Illicit Drug Data Report 2020–2021. Canberra: ACIC, accessed 24 October 2023.

ACIC (2024) National Wastewater Drug Monitoring Program Report 21. Canberra: ACIC, accessed 14 March 2024.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2024) National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2022–2023. AIHW, accessed 22 February 2024.

NDARC (National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre) (2016) New (and emerging) psychoactive substances (NPS) fact sheet, accessed 21 December 2017.

NDARC (2021) Ketamine fact sheet, accessed 4 April 2024.

NSW Ministry of Health (2017). A quick guide to drugs & alcohol, 3rd edn. Sydney: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre.

Sutherland R, Allsop S, and Peacock A (2020) New psychoactive substances in Australia: Patterns and characteristics of use, adverse effects, and interventions to reduce harm. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 33(4):343-351, doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000606

Sutherland R, Karlsson A, King C, Uporova J, Chandrasena U, Jones F, Gibbs D, Price O, Dietze P, Lenton S, Salom C, Bruno R, Wilson J, Grigg J, Daly C, Thomas N, Radke S, Stafford L, Degenhardt L, Farrell M, & Peacock A (2023) Australian Drug Trends 2023: Key Findings from the National Ecstasy and Related Drugs Reporting System (EDRS) Interviews. Sydney: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, UNSW Sydney. Accessed 25 October 2023.

UNODC (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime) (2022) World Drug Report 2022. Vienna: UNODC, accessed 6 July 2022.

UNODC (2024) What are NPS?, UNODC Early Warning Advisory on New Psychoactive Substances, UNODC, accessed 14 June 2024.