People with mental health conditions

Key findings

View the People with mental health conditions fact sheet >

Mental health is fundamental to the wellbeing of individuals, their families, and the population as a whole (ABS 2018). According to the 2022–2023 National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS) estimates, 18.0% of the general population aged 14 and over had been diagnosed or treated for a mental health condition in the previous 12 months. This increased from 16.9% in 2019 (AIHW 2024, Table 10.16). The proportion of people aged 18 and over experiencing high or very high levels of psychological distress also increased, from 14.0% in 2019 to 16.6% in 2022–2023 (AIHW 2024, Table 10.16).

Increasing literacy and awareness around mental illness in Australia may partially explain these reported increases (National Mental Health Commission of NSW 2015), however, there are likely to be other factors involved including changing trends and patterns in alcohol and other drugs use.

There is a complex relationship between mental health and alcohol and other drug use. A mental illness may make a person more likely to use drugs to provide short-term relief from their symptoms, while other people have drug problems that may trigger the first symptoms of mental illness (AIHW 2024). It is often difficult to determine whether mental illness preceded substance use or vice versa. In particular, self-reported survey data (such as that reported in the NDSHS) do not establish a causal link between mental health conditions and drug use (AIHW 2024).

The ABS National study of mental health and wellbeing reports 12-month mental disorders as the number of people who met the diagnostic criteria for a mental disorder at some time in their life and had sufficient symptoms of that disorder in the previous 12 months. The 2020–2022 study found:

- 3.3% of Australians (647,900 people) aged 16–85 years had symptoms of a 12-month Substance Use disorder.

- 4.4% of males reported a 12-month Substance Use disorder, compared with 2.1% of females (ABS 2023).

Tobacco smoking

Tobacco smoking has declined among people with mental health conditions or high or very high psychological distress but remains higher among these groups than people without mental health conditions (AIHW 2024). According to 2022–2023 NDSHS estimates:

- between 2019 and 2022–2023, there were significant decreases in the proportion of people who smoked daily among those with mental health conditions (from 20% to 15.4%) or high or very high levels of psychological distress (from 21% to 15.3%)

- the proportion of people with high or very high psychological distress who had never smoked increased, from 54% in 2019 to 59% in 2022–2023

- however, in 2022–2023, people with mental health conditions were still twice as likely to smoke daily as people who had not been diagnosed or treated for mental health conditions (15.4% compared with 7.4%)

- people who reported high or very high levels of psychological distress were also twice as likely to report daily smoking as those who reported low psychological distress (15.3% compared with 6.7%) (AIHW 2024, Tables 10.18 and 10.20; Figure MENTALHEALTH 1).

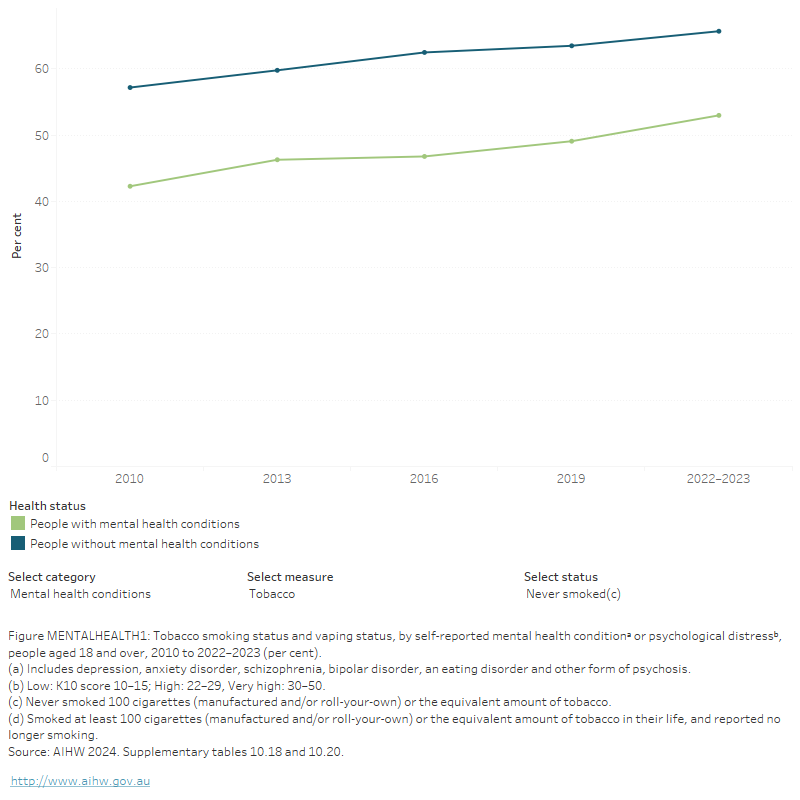

FIGURE MENTALHEATLH 1: Tobacco smoking status and vaping status, by self-reported mental health conditionᵃ or psychological distressᵇ, people aged 18 and over, 2010 to 2022–2023 (per cent)

The figure shows that, between 2010 and 2019, the proportion of daily smokers who reported having a mental health condition steadily decreased from 26.5% in 2010 to 20.2% in 2019. Among people who had never smoked, the proportion of people with a self-reported mental health condition changed from 42.3% in 2010 to 49.1% in 2019.

The 2020–2022 National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing showed that of people aged 16–85 whose smoking status was:

- currently smoked:

- never smoked:

- 1 in 5 (23%) had any 12-month mental health disorder.

- 1.8% of people had substance use disorders.

- Males were more likely to have had substance use disorders than their female counterpart (2.8% compared with 0.9%) (ABS 2023, Table 5.3).

The mechanisms linking tobacco smoking with mental health conditions are complex; however, it is understood that people may perceive smoking to be helpful in relieving or managing the psychiatric symptoms associated with their disorder (Minichino et al. 2013). It has also been shown that people with mental health conditions may find smoking cessation difficult. However, upon quitting, they are likely to experience improvements in their mood, general wellbeing, mental health and quality of life (Greenhalgh et al. 2018).

Alcohol consumption

New Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol were released in December 2020.

People with mental health conditions or high or very high levels of psychological distress are more likely to drink at risky levels than people without these conditions. The 2022–2023 NDSHS findings showed that:

- people with mental health conditions were more likely to drink at risky levels than those without mental health conditions (37% compared with 32%)

- people with high or very high levels of psychological distress were more likely to report drinking at risky levels than those who reported low psychological distress (39% compared with 30%)

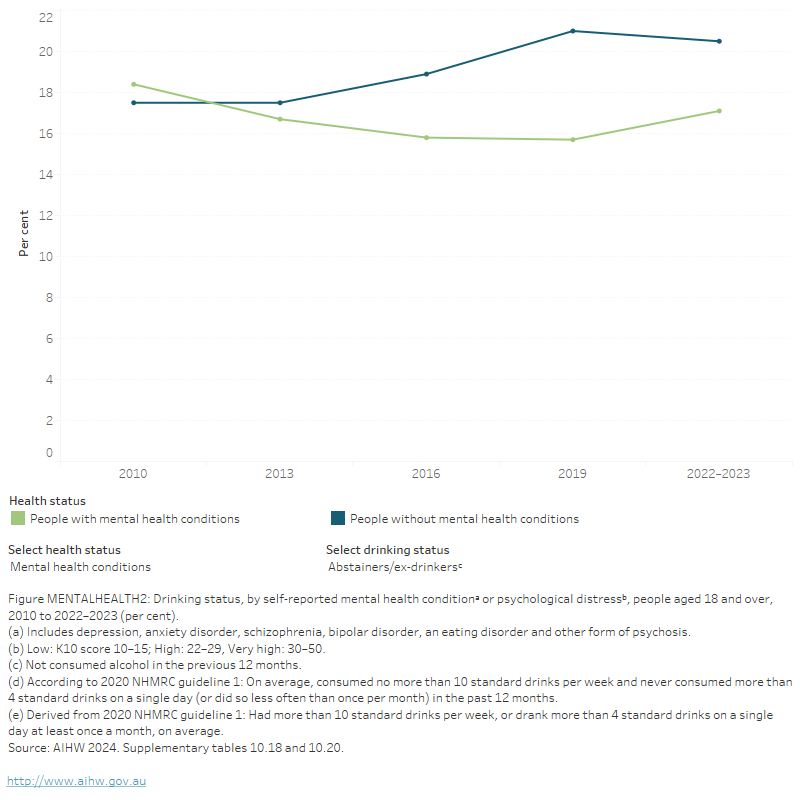

- between 2019 and 2022–2023, the proportion of abstainers/ex-drinkers increased among those with mental health conditions but remained stable among those without mental health conditions (AIHW 2024, Table 10.20; Figure MENTALHEALTH 2).

The 2020–2022 National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing showed that of people aged 16–85 whose alcohol consumption was:

- nearly every day:

- Just over 1 in 5 (23%) of people had any 12-month mental disorder.

- 8.5% of people had substance use disorders.

- Males and females had similar proportions of substance use disorders (8.4% and 8.7%, respectively).

- 1–3 days a month:

- Just over 1 in 4 (23%) of people had any 12-month mental disorders.

- 3.1% of people had substance use disorders.

- Males were more likely to have had substance use disorders than their female counterpart (4.5% compared with 0.8%) (ABS 2023, Table 5.3).

FIGURE MENTALHEALTH 2: Drinking status, by self-reported mental health conditiona or psychological distressb, people aged 18 and over, 2010 to 2022–2023 (per cent)

The figure shows that the proportion of people with a self-reported mental health condition was highest among those who exceeded single occasion risky drinking levels (30.9%) or exceeded lifetime risk (21.3%).

Illicit drugs

The NDSHS found that, in 2022–2023, compared with people without mental health conditions, people with a mental health condition were:

- 1.8 times as likely to have recently used any illicit drug (29% compared with 15.9%)

- 2.0 times as likely to have used cannabis (19.8% compared with 10.0%)

- about 3.9 times as likely to have used methamphetamines or amphetamines (2.7% compared with 0.7%)

- 1.5 times as likely to have used ecstasy (3.0% compared with 2.0%)

- 1.6 times as likely to have used cocaine (6.9% compared with 4.4%)

- 2.5 times as likely to use ketamine (3.0% compared with 1.2%) (Figure MENTALHEALTH 3; AIHW 2024, Table 10.20).

The 2020–2022 National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing showed that of people aged 16–85 whose misuse of drugs was:

- At least once a week:

- 3 in 5 (58%) of people had any 12-month mental disorders.

- Over 1 in 4 (29%) of people had substance use disorders.

- Males were more likely to have had substance use disorders than their female counterparts (29% compared with 26%).

- Less than once a month:

- Over 2 in 5 (44%) of people had any 12-month mental disorders.

- 13% of people had substance use disorders.

Similar proportions of males and females had substance use disorders (13% and 14%, respectively) (ABS 2023, Table 5.3).

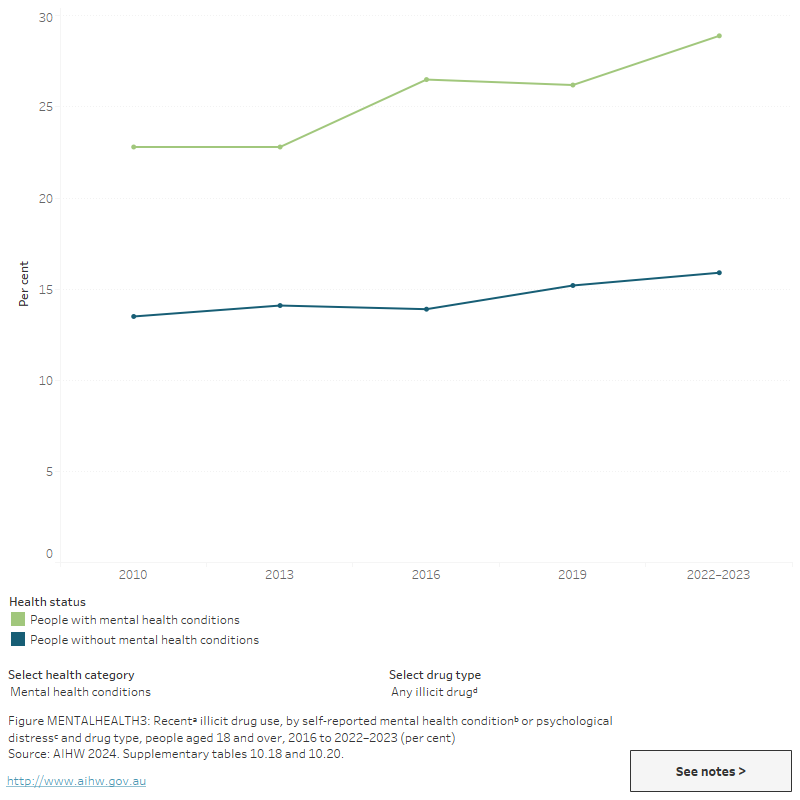

Figure MENTALHEALTH 3: Recentᵃ illicit drug use, by self-reported mental health conditionᵇ or psychological distressᶜ and drug type, people aged 18 and over, 2010 to 2022–2023 (per cent)

Figure MENTALHEALTH3: Recent illicit drug use, by self-reported mental health condition and psychological distress and drug type, people aged 18 and over, 2010 to 2019 (per cent)

The figure shows that the proportion of people who had recently used any illicit drug and experienced psychological distress increased between 2010 and 2016 (from 25.2% to 30.8%). This pattern was true for cannabis, cocaine and ecstasy.

Use of specific illicit drugs among people with mental health conditions and high psychological distress has varied across time and by drug type. Between 2019 and 2022–2023:

- there were significant increases in the proportion of people with mental health conditions that reported recent use of hallucinogens (from 2.4% in 2019 to 4.0% in 2022–2023) and ketamine (from 1.9% in 2019 to 3.0% in 2022–2023) (AIHW 2024, Table 10.20)

- among people with high or very high levels of psychological distress, recent use of ecstasy decreased from 6.1% to 4.6%

- recent use of ecstasy decreased from 6.1% to 4.6% among people with high or very high levels of distress (AIHW 2024, Table 10.18).

Injecting drug use

For related content on injecting drug use, see also:

Results from the 2023 Illicit Drug Reporting System (IDRS) showed that 53%of participants self-reported that they had experienced a mental health problem in the previous 6 months, stable from 2021 (47%). The most commonly reported mental health problems were depression (64%) and anxiety (55%). Fifty-five per cent of these people had seen a mental health professional in the previous 6 months, down from 58% in 2021 (Sutherland et al. 2022).

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2018) Mental health, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 14 June 2024.

ABS (2023) National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing 2020–22. ABS cat no.4326.0. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 28 November 2023.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2024) National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2022–2023. AIHW, accessed 13 February 2024.

Greenhalgh EM, Stillman S, & Ford C (2018) 9A.3 People with substance use and mental disorders. In Scollo, MM and Winstanley, MH [editors]. Tobacco in Australia: Facts and issues. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria. Viewed 30 January 2023.

Minichino A, Bersani FS, Calo WK, Spagnoli F, Francesconi M, et al. (2013) Smoking behaviour and mental health disorders--mutual influences and implications for therapy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 10(10):4790–811.

National Mental Health Commission of NSW (2015) National Surveys of Mental Health Literacy and Stigma and National Survey of Discrimination and Positive Treatment: A report for the Mental Health Commission of NSW (PDF). Sydney: Mental Health Commission of NSW.

Sutherland R, Uporova J, King C, Chandrasena U, Karlsson A, Jones F, Gibbs D, Price O, Dietze P, Lenton S, Salom C, Bruno R, Wilson J, Agramunt S, Daly C, Thomas N, Radke S, Stafford L, Degenhardt L, Farrell M, & Peacock A (2023) Australian Drug Trends 2023: Key Findings from the National Illicit Drug Reporting System (IDRS) Interviews. Sydney: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, UNSW Sydney. Accessed 25 October 2023.