Younger people

Key findings

View the Younger people fact sheet >

Experimentation with alcohol and other drugs is a part of the lives of many young people, though use of tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drugs is less common among young people in 2022–2023 than their same-age peers in 2001 (AIHW 2024b, Table 5.8). Drug use among young people remains concerning as these age groups (particularly adolescents) are susceptible to permanent damage from alcohol and other drug use as their brains are still developing, which makes them a vulnerable population. Refer to Box YOUNGER 1 on how young people are defined in this report.

Box YOUNGER 1: How do we define ‘young’?

In 2022, there were 6.6 million people aged 10–29 in Australia and of these 3.2 million were aged 15–24 years (ABS 2023b).

There is no standard definition of ’young people’. The availability and quality of alcohol, tobacco and other drug use data on younger people varies depending on the data source. For example, data sources in this report provide data for younger people ranging from:

- 15–24 years (such as the Australian Burden of Disease data)

- 12–17 years (such as the Australian Secondary Students’ Alcohol and Drug survey),

- 10–29 years (such as the Alcohol and Other Drug Treatment Services National Minimum Data Set).

The National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS) collects data on younger people between 14–24, with most data presented in this report relating to young adults aged between 18–24. Some data sources can be disaggregated by different age groups, refer to supplementary tables for further information.

Tobacco and e-cigarettes

For related content on younger people and tobacco smoking by state/territory, see also:

Data from multiple sources indicates that the prevalence of tobacco smoking among people in younger age groups is decreasing (AIHW 2024b, Scully et al. 2023a). This appears to be driven by a higher proportion of young adults not taking up smoking. According to the NDSHS estimates, in 2022–2023:

- 98% of people aged 14–17 had never smoked, increasing from 82% in 2001

- About 4 in 5 (83%) people aged 18–24 had never smoked, up from 58% in 2001 (AIHW 2024b, Table 2.4).

The proportion of younger people who smoke appears to rise with increasing age. Estimates from the 2022–2023 NDSHS indicate that 9.4% of people aged 18–24 currently smoke compared with *1.6% of people aged 14–17 (AIHW 2024b, Table 2.4).

* Estimate has a relative standard error of 25% to 50% and should be used with caution.

Additionally, the 2022–2023 Australian Secondary Students Alcohol and Drug (ASSAD) survey of 10,300 secondary students aged 12–17 found that:

- 13.5% of students reported smoking at least part of a tobacco cigarette in their lifetime, down from 17.5% in 2017.

- 3.4% of secondary school students aged 12–17 had smoked in the last month, a decrease from 7.5% in 2017.

- 50% of people who currently smoke stated that their most common source for cigarettes was from friends (Scully et al. 2023a).

Daily smoking

The proportion of young adults who smoke daily has been declining since 2001 (AIHW 2024b). Estimates from the NDSHS showed, in 2022–2023:

- 5.9% people aged 18–24 smoked daily, down from 24% in 2001. This was consistent for both males (from 24.5% in 2001 to 6.9% in 2022–2023) and females (23.5% to 5.0%) (AIHW 2024b, Table 2.4).

- Among people aged 14–17, daily smoking decreased from 11.2% in 2001 to **0.9% in 2022–2023.

** Estimate has a high level of sampling error (relative standard error of 51% to 90%), meaning that it is unsuitable for most uses.

This is supported by the ASSAD survey, that found 1 in 50 (2.1%) students aged 12–17 were currently smoked, that is, smoked on at least 1 of the past 7 days; this is lower than the 4.9% reported in 2017 (Scully et al. 2023a).

This trend was similar for young First Nations people aged 15–24, with the proportion of people who currently smoke daily decreasing from 45% in 2002 to 31% in 2014–15 (AIHW 2018a). More young First Nations females (61% or 41,600) than males (53% or 36,300) had never smoked and more males than females smoked daily (35% or 23,600 and 27% or 18,200, respectively) in 2014–15 (AIHW 2018a).

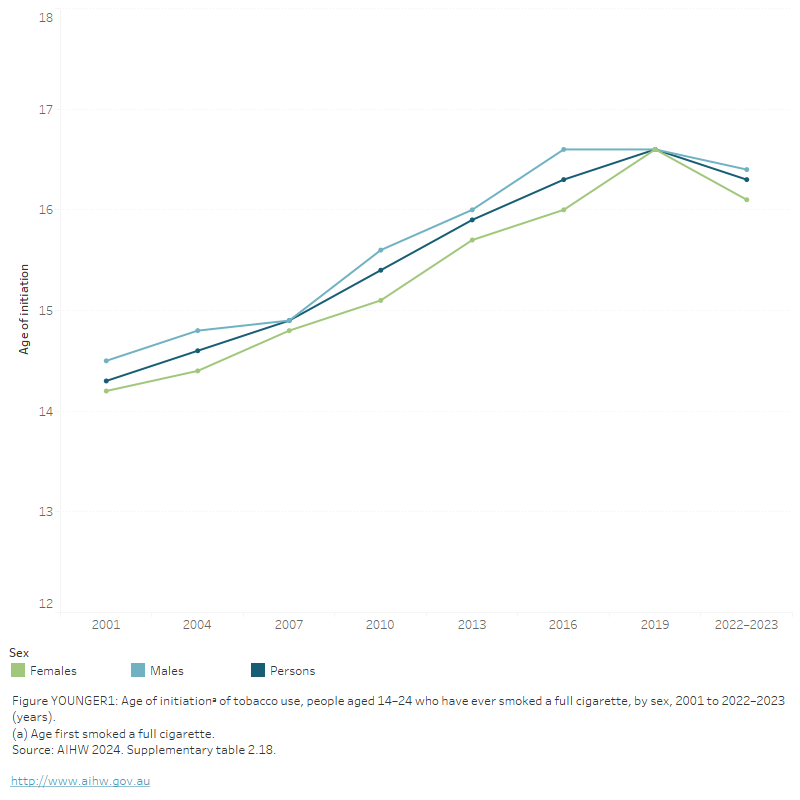

Age of initiation

The average age at which younger people aged 14–24 smoked their first full cigarette has steadily risen since 2001, for both males and females (AIHW 2024b, Table 2.18). According to NDSHS estimates:

- In 2022–2023, the age at which younger people tried smoking their first full cigarette (16.3 years) was 2 years older than in 2001 (14.3 years).

- Between 2019 and 2022–2023, the average age of smoking initiation among females decreased from 16.6% to 16.1%. For males, it remained stable (from 16.6% to 16.4%) (Figure YOUNGER 1).

FIGURE YOUNGER 1: Age of initiationᵃ of tobacco use, people aged 14–24 who have ever smoked a full cigarette, by sex, 2001 to 2022–2023 (years)

The figure shows that the age of initiation for tobacco use among people aged 14–24 has steadily increased from 14.2 years in 1995 to 16.3 years in 2016. This pattern is similar for both males (rising from 14.5 years in 2001 to 16.6 years in 2019) and females (from 14.2 years to 16.6 years).

Number of cigarettes

In 2022–2023, the number of cigarettes smoked per day by those in the 18–24 age group continued to decline. In 2001, people aged 18–24 who smoked used an average of 11.1 cigarettes per day, declining to 8.1 cigarettes per day in 2016 and a further decline to 7.0 cigarettes per day in 2022–2023 (AIHW 2024b, Table 2.8). The proportion of people aged 18–24 who smoked a pack a day remained stable from 2019 (19.4%) to 2022–2023 (*17.9%) (AIHW 2024b, Table 2.7).

* Estimate has a relative standard error of 25% to 50% and should be used with caution.

Types of tobacco products consumed

Use of roll-your-own (RYO) cigarettes had been increasing among younger people since 2001. However, estimates from the 2022–2023 NDSHS showed decreases in use between 2019 and 2022–2023. Specifically:

- People aged 18–24 were the most likely age group to currently use RYO cigarettes or to have used an e-cigarette in their lifetime.

- About 2 in 5 (43%) people aged 18–24 who smoked currently used RYO cigarettes, a decrease from 2019 (63%). This is similar to the findings for people aged 14 and over where there was a decrease from 45% in 2019 to 41% in 2022–2023 (AIHW 2024b, Table 2.23).

Additionally, the 2022–2023 ASSAD survey found that among secondary school students aged 12–17, 52% of people who smoked in the past have used RYO tobacco, down from 55% in 2017 (Scully et al. 2023a).

Use of e-cigarettes/vapes

The use of e-cigarettes is greater among younger people than those in older age groups. Estimates from the 2022–2023 NDSHS showed that among people aged 18–24:

- almost half (49%) had used an e-cigarette in their lifetime, the largest proportion of any age group (AIHW 2024b, Table 3.1).

- 1 in 5 (21%) reported current use (AIHW 2024b, Table 3.3)

- 87% of people who currently smoke in this age group had used an e-cigarette. This has increased significantly since 2019, when 26% of people and 64% of people aged 18–24 who currently smoke had ever used an e-cigarette (AIHW 2024b, Table 3.1).

- over half (58%) of people who had ever used an e-cigarette reported that they had never smoked the first time they tried an e-cigarette (AIHW 2024b, Table 3.28).

- over 3 in 4 (77%) people who currently used e-cigarettes reported that the last e-cigarette used contained nicotine, while 13% were unsure (AIHW 2024b, Table 3.18).

- ho had used e-cigarettes in the last 30 days, 26% had used them daily while 18.7% used them once every couple of weeks (AIHW 2024b, Table 3.22).

The 2022–2023 NDSHS showed that among those aged 14–17:

- 28% had used an e-cigarette in their lifetime, up from 9.6% in 2019 (AIHW 2024b, Table 3.1)

- 1 in 10 (9.7%) reported current use (AIHW 2024b, Table 3.3).

Data from the 2022–2023 ASSAD survey found that:

- Approximately 30% of secondary school students had tried e-cigarettes, 16% had vaped at least once in the past month and 4.8% on at least 20 days in the past month.

- 69% of secondary school students who had ever tried vaping reported that they had not previously smoked a cigarette before their first vape.

- Almost two-thirds (64%) of students who had vaped in the past month believed the vape they used contained nicotine.

- 80% of students who had vaped in the past month used a disposable vaping device (Scully et al. 2023a).

Geographic trends

According to the 2022–2023 NDSHS, 5.9% of young adults aged 18–24 reported daily smoking, a decrease from 9.2% in 2019. Most states and territories reported a decrease in young adults aged 18–24 who reported daily smoking, however, the decrease was only significant in New South Wales (from 7.8% in 2019 to 3.5% in 2022–2023) (AIHW 2024b, Table 9b.7). In Victoria, there was an increase in daily smoking among people 18–24, from 6.4% in 2019 to 7.7% in 2022–2023.

Alcohol consumption

For related content on younger people and alcohol consumption by state/territory, see also:

New Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol were released in December 2020.

The Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol advise that children and people under 18 years of age should not drink alcohol (NHMRC 2020). Drinking alcohol in adolescence can be harmful to young people’s physical and psychosocial development.

Results from the 2022–2023 NDSHS indicate that younger people are increasingly following this advice, with the age at which people first tried alcohol rising over time. Specifically:

- The average age at which young people aged 14–24 first tried alcohol has steadily risen from 14.7 years in 2001 to 16.1 in 2022–2023.

- Among those aged 14–24, the average age of initiation for males increased from 16.1 in 2019 to 16.2 in 2022–2023, while for females it decreased from 16.3 to 16.1 (AIHW 2024b, Table 4.13).

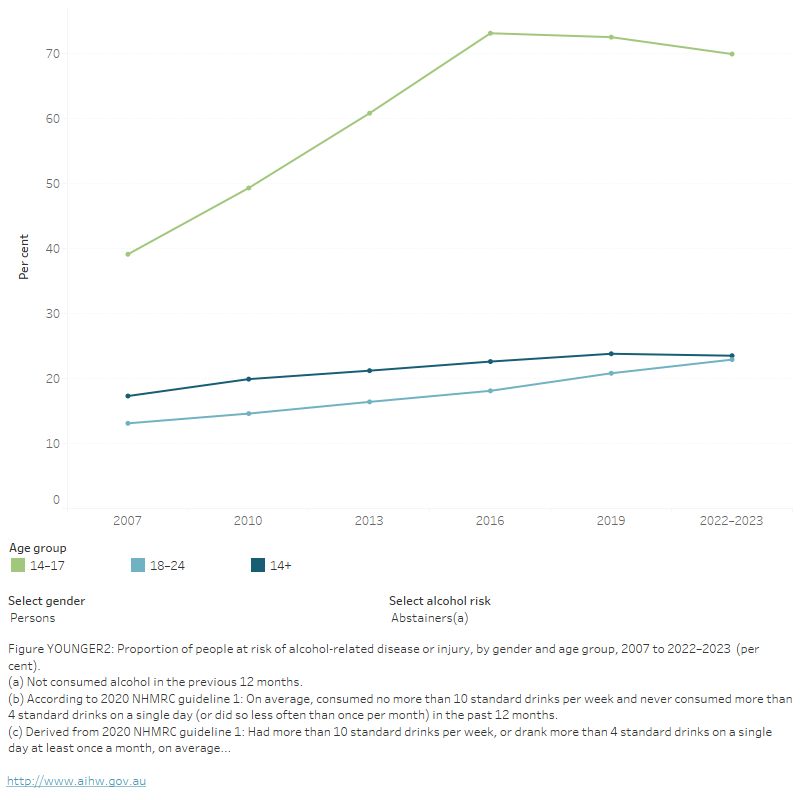

There has also been a long-term increase in the proportion of young people who abstain from alcohol. From 2007 to 2022–2023, the proportion of people aged 14–17 who abstained increased from 39% to 70%, while for people aged 18–24 it rose from 13.1% to 23%. These proportions remained stable from 2019 to 2022–2023 (AIHW 2024b, Table 4.28).

Similarly, findings from the 2022–2023 ASSAD survey showed that:

- Less than 1 in 2 (44%) of those aged 12–17 drank alcohol in the past year, similar to 56% in 2017.

- 22% had drunk alcohol in the past month, a decrease from 27% in 2017.

- 47% of students who were current drinkers obtained alcohol from their parents.

- Nearly half (47%) of current drinkers most commonly drank premixed spirits (Scully et al. 2023b).

Risky drinking

Younger people are more likely than any other age group to consume alcohol that exceeds the risk guidelines by consuming on average more than 4 standard drinks on a single day at least monthly, or more than 10 standard drinks in a week. Estimates from the 2022–2023 NDSHS indicate that:

- Young adults aged 18–24 were the most likely of all age groups to be at risk of alcohol-related disease or injury (42%), compared with 31% of people aged 14 and over (AIHW 2024b, Table 4.27).

- There has been an overall reduction in the proportion of young people aged 18–24 years exceeding risk guidelines, from 56% in 2010 to 42% in 2022–2023 (Figure YOUNGER 2).

- 1 in 5 (21%) young people aged 18–24 reported drinking more than 4 standard drinks in a single day, at least weekly (AIHW 2024b, Table 4.30).

- Almost 1 in 4 (28%) of young people aged 18–24 reported drinking more than 10 standard drinks a week on average in the previous 12 months. This has remained stable since 2019 (25%) (AIHW 2024b, Table 4.29).

- Among females aged 18–24 there was a significant increase in those drinking more than 10 standard drinks per week on average, from 15.9% in 2019 to 25% in 2022–2023. For males of the same age, this proportion remained stable (from 33% in 2019 to 32% in 2022–2023) (AIHW 2024b, Table 4.29).

- The proportion of young people aged 14–17 exceeding the adult risk guidelines showed a significant decrease between 2019 and 2022–2023 (9.5% to 5.5%) (AIHW 2024b, Table 4.28).

Data from the ASSAD survey also showed a decrease in the proportion of risky drinkers aged 16–17 (those who drank 5 or more drinks on any day in the past week), from 10.8% in 2017 to 8.8% in 2022–2023 (Scully et al. 2023b).

Figure YOUNGER 2: Proportion of people at risk of alcohol-related disease or injury, by gender and age group, 2007 to 2022–2023 (per cent)

The figure shows that the proportion of people aged 18–24 who exceeded the lifetime risk guidelines for alcohol decreased from 31.0% in 2010 to 18.8% in 2019 nationally. The proportion of people aged 14–17 exceeding the lifetime risk guidelines also decreased from 8% in 2010 to 2.2% in 2019.

In the 2022–2023 NDSHS, alcohol consumption at high levels was more common among younger people than the general population. Specifically, people aged 18–24 (14.8%) were more likely to consume 11 or more standard drinks at least monthly than people in other age groups (AIHW 2024b, Table 4.32).

These data are supported by findings from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey. Between 2002 and 2021, males and females aged 20–24 were more likely than people in other age groups to drink 5 or more drinks on one occasion (42.0% of males and 27.7% of females who drank alcohol) (Wilkins et al. 2024).

Findings from the ABS’s Alcohol Consumption Financial Year 2020–21 reported that 26% of people aged 18–24 exceeded the 2020 alcohol guideline, consuming either more than 10 drinks in the last week and/or consumed 5 or more drinks on any day at least monthly in the last 12 months (12 occasions per year). These survey data were collected online during the COVID-19 pandemic and is a break in time series. Data should be used for point-in-time analysis only and can’t be compared to previous years (ABS 2022a). See Box ALCOHOL 1: Summary of the Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol.

The 2016–17 Young Australians Alcohol Reporting System (YAARS) examines risky drinking behaviours of the top 25% of drinkers aged 14–19 in more detail. The general trends from the YAARS data are similar to that of the NDSHS, but also show that:

- Risky drinkers started their drinking around 2 years earlier (14 years) than the national average for recent and ex-drinkers aged 14–24 from the 2022–2023 NDSHS (16.1 years).

- Around half were consuming 11 or more standard drinks on one occasion at least once a month, and their average drinking duration was 6.4 hours (Lam et al. 2017).

Geographic trends

Overall, since 2007, the proportion of young adults aged 18–24 consuming more than 10 standard drinks per week on average has decreased in every jurisdiction. Between 2019 and 2022–2023:

- New South Wales was the only state to report an increase in people aged 18-24 drinking more than 4 standard drinks in a single day at least once a month (from 37% in 2019 to 48% in 2022–2023. This was greater than the level reported in 2007 (46%) AIHW 2024b, Table 9b.24).

- Most jurisdictions reported a decrease in the proportion of young adults at risk of alcohol-related harm. The exception to this was New South Wales and South Australia (AIHW 2024b, Table 9b.22).

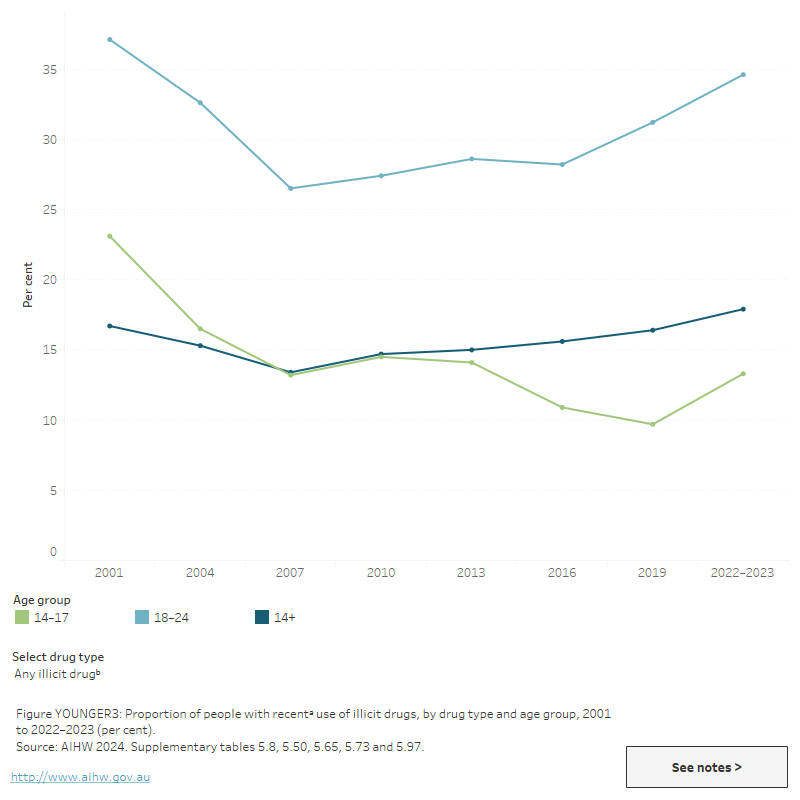

Illicit drugs

For related content on younger people and illicit drug use by state/territory, see also:

Estimates from the 2022–2023 NDSHS showed that over 1 in 3 (35%) people aged 18–24 and just under 1 in 8 (13.3%) aged 14–17 had used illicit drugs in the last 12 months (AIHW 2024b, Table 5.8). People aged 18–24 were more likely to have recently used illicit drugs than people in any other age group, and this proportion has increased from 27% in 2007. Cannabis, cocaine, and ecstasy are the drugs that are most commonly used by people aged 18–24 (AIHW 2024b, Table 5.26 Figure YOUNGER 3).

Figure YOUNGER 3: Proportion of people reporting recenta use of illicit drugs, by drug type and age group, 2001 to 2022–2023 (per cent)

The figure shows that the proportion of people aged 18–24 who have recently used any illicit drug has remained relatively stable from 2010 (27.4%) to 2019 (31.2%), nationally.

Age of initiation

In 2022–2023, the average age at which people first tried any illicit drug was 19.5 years. This was younger than the age of initiation in 2019 (19.9 years) but has increased overall since 2001 (18.6 years). The average age of initiation has increased since 2001 for a range of drugs including cannabis, cocaine, hallucinogens and inhalants (AIHW 2024b, Table 5.17).

The HILDA Survey includes data on people who started using illicit drugs between 2017 and 2021, including people who may have resumed using drugs after previously stopping (Wilkins et al. 2024). These data show that around 1 in 5 people (19.0%) aged 20–24 started (or resumed) illicit drug use between 2017 and 2021, higher than any other age group.

Cannabis

Estimates from the NDSHS show that people aged 18–24 continue to be the most likely age group to use cannabis, and cannabis is the most widely used drug among this age group (AIHW 2024b). In 2022–2023, one-quarter (25.5%) of people in this age group had used cannabis in the past 12 months, compared with 11.5% of people aged 14 and over (AIHW 2024b, Table 5.50). However, recent use of cannabis has declined among this cohort since 2001 (32%) but remained stable between 2019 (25.4%) and 2022–2023 (AIHW 2024b).

In 2022–2023, 9.7% of people aged 14–17 had recently used cannabis. This represents a decrease from 21% in 2001, and a slight increase from 8.2% in 2019 (AIHW 2024b, Table 5.50).

The ASSAD survey reported that:

- In 2022–2023, 6.6% of students aged 12–17 had used cannabis in the month before the survey and 13.4% reported using cannabis in their lifetime, making cannabis the most commonly used drug in this cohort (Scully et al. 2023b, Table 6).

- There was a decrease in the proportion of young people aged 16–17 who had used cannabis both in their lifetime (30% in 2017 compared with 24% in 2022–2023) in the past month (15.7% in 2017 compared with 11.3% in 2022–2023) (Scully et al. 2023b, Figure 14).

Stimulant use

Use of methamphetamines or amphetamines among younger people is similar to that of older people. Estimates from the 2022–2023 NDSHS showed that:

- 3.6% of people aged 18–24 had used methamphetamines or amphetamines in their lifetime while 1.7% had used them in the previous 12 months (AIHW 2024b, Table 5.83). .

- 3 in 5 (68%) people aged 18–24 who had used methamphetamine or amphetamine in the last 12 months had done so only once or twice (AIHW 2024b, Table 5.87).

Recent use of cocaine and ecstasy has changed since 2019. The 2022–2023 NDSHS estimates suggest that among people aged 18–24:

- Recent use of cocaine increased from 2019 (10.8%) to 2022–2023 (11.3%), with a significant increase for females (8.0% to 11.9%) (AIHW 2024b, Table 5.65).

- Recent use of ecstasy has been fluctuating since 2001 (11.7%), but significantly decreased from 2019 (10.8%) to 2022–2023 (6.7%). This was driven by a decrease in recent use among males (from 12.6% in 2019 to 8.3% in 2022–2023) (AIHW 2024b, Table 5.73).

Findings from the 2022–2023 ASSAD survey reveal similar results. Of secondary school students aged 12–17, 1.7% have tried amphetamines, 1.9% have tried cocaine and 3.2% have tried ecstasy (Scully et al. 2023b, Table 7).

Other drugs

Other drugs that are used by young people include inhalants, hallucinogens, ketamine, new and emerging psychoactive substances, and tranquilisers and other pharmaceuticals for non-medical purposes (AIHW 2024b, Scully et al. 2023b). The 2022–2023 ASSAD survey showed that, among students aged 12–17:

- Around 1 in 5 (18.0%) students had ever used tranquilisers for a non-medical reason, 5.6% had used them in the past month (Scully et al. 2023, Table 5). This is higher than 2022–2023 NDSHS estimates (*2.0% for lifetime use among people aged 14–17, and **0.5% for use in the past 12 months) (AIHW 2024b).

- 20% of students had deliberately sniffed inhalants at least once in their lifetime, with 7.4% reporting doing so in the past month (Scully et al. 2023b, Table 7).

- 2% of students reported they had used synthetic cannabis in the last 12 months (Scully et al. 2023b).

* Estimate has a relative standard error of 25% to 50% and should be used with caution.

** Estimate has a high level of sampling error (relative standard error of 51% to 90%), meaning that it is unsuitable for most uses.

Additionally, the NDSHS has showed that use of certain drugs among younger people aged 18–24 has increased over time (AIHW 2024b). Specifically:

- Use of ketamine rose from 1.6% in 2016 to 4.6% in 2022–2023.

- The proportion of people who have recently used hallucinogens has fluctuated over time, with 6.4% of those aged 18–24 reporting recent use in 2022–2023 (AIHW 2024b, Table 5.97).

Geographic trends

Data from the 2022–2023 NDSHS showed that the proportion of 18–24 year olds who reported recent illicit drug use has fluctuated over time and within jurisdictions. In 2022–2023, the Australian Capital Territory had the highest proportion of people aged 18–24 who reported recent drug use (43%) while New South Wales had the lowest (31%) (AIHW 2024b, Table 9b.31).

Health and harms

For related content on health and harms, see also:

Burden of disease

The Australian burden of disease study 2018 found that in young people (aged 15–24):

- Alcohol use and illicit drug use were the leading causes of the total burden of disease in males.

- Alcohol use and illicit drug use were the second and third leading causes (respectively) of disease burden in females (AIHW 2021).

Alcohol-related harm

Younger people are also more likely to be victims of alcohol-related incidents. In 2022–2023, 1 in 3 (33%) people aged 18–24 had been the victim of any alcohol-related incident (including physical and verbal abuse and being put in fear) in the previous 12 months. This was higher than for any other age group (AIHW 2024b, Table 4.56).

Furthermore, 83% of risky drinkers aged 14–19 years reported that they were injured as a result of their drinking in the past 12 months and 7% attended the emergency department for an alcohol related injury (Lam et al. 2017).

Deaths due to harmful alcohol consumption

Alcohol-induced deaths are defined as those that can be directly attributable to alcohol use, as determined by toxicology and pathology reports (for example, chronic conditions such as alcoholic liver cirrhosis or acute conditions such as alcohol poisoning). Alcohol-related deaths include deaths directly attributable to alcohol use and deaths where alcohol was listed as an associated cause of death (for example, a motor vehicle accident where a person recorded a high blood alcohol concentration) (ABS 2018).

See also Health impacts: Deaths due to harmful alcohol consumption.

In 2022, ABS Causes of Death data reported 1,742 alcohol-induced deaths. Of these deaths, 3% (or 53 deaths) were in people aged 15–34, with this age group experiencing the lowest rate of death at (0.8 deaths per 100,000 population) (ABS 2023a, Table 13.12). In addition:

- 72% of these alcohol-induced deaths were from the chronic effects of alcohol (ABS 2023a, Table 13.16).

- Overall, the lowest age-specific rate for both females and males was for those aged 15–34 years (0.5 and 1.0 per 100,000 population, respectively) (ABS 2023a, Table 13.12).

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) analysis of the AIHW National Mortality Database reported 1,742 alcohol-induced deaths and 4,981 alcohol-related deaths in 2022:

- There were 0.3 deaths per 100,000 people for alcohol-induced deaths for people aged 20–24. This compares with the highest rate of 18.1 per 100,000 population for people aged 55–59.

- For alcohol-related deaths, the rate for people aged 15–19 was 2.3 per 100,000 population, a decrease from 3.8 per 100,000 population in 2021.

- For those aged 20–24 the rate of alcohol-related deaths was 7.6 per 100,000 population, an increase from 7.4 per 100,000 population in 2021.

- These rates compare with the highest rate of alcohol-related death in 2022 of 41.9 per 100,000 people for those aged 60–64 (Table S1.5).

Drug-induced deaths

Drug-induced deaths are defined as those that can be directly attributable to drug use and includes both those due to acute toxicity (for example, drug overdose) and chronic use (for example, drug-induced cardiac conditions) as determined by toxicology and pathology reports (ABS 2023a).

In 2022, ABS Causes of Death data reported 1,693 drug-induced deaths. Of these deaths, 6.3% (106 deaths) were in people aged 15–24 years. This age group had the lowest age-specific rate of death, 3.3 deaths per 100,000 population (ABS 2023, Table 13.2).

- Overall, the lowest age-specific rate for both females and males was for those aged 15–24 (2.0 and 4.6 per 100,000 population, respectively) (ABS 2023a, Table 13.2).

The majority of these deaths were accidental (69%) (ABS 2023a, Table 13.3).

Analysis by the National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre indicates that people aged 15–24 have low rates of drug-induced deaths across most drug types, including opioids (2.3 deaths per 100,000 in 2022), amphetamine-type stimulants (1.0 per 100,000 in 2022), and cocaine (0.38 per 100,000) (Chrzanowska et al. 2024).

AIHW analysis of the National Mortality database shows that in 2022, 22% of drug-induced deaths among people aged 15–24 had a personal history of self-harm, making this the most frequently occurring psychosocial risk factor among this group (Table S2.7).

Mental health

Among participants in the 2022–23 Australian Secondary Students’ Alcohol and Drug (ASSAD) survey, 2% of students reported seeking help from a health professional for alcohol and/or drug related problems (Scully et al. 2023b).

Treatment

The Alcohol and Other Drug Treatment Services National Minimum Data Set (AODTS NMDS) provides information on treatment provided to clients by publicly funded AOD treatment services, including government and non-government organisations. Data collected for the AODTS NMDS are released twice each year, via an early insights report in April and a detailed annual report mid-year. For the purposes of the AODTS NMDS, young people are defined as those aged between 10 and 29 years.

The latest Alcohol and other drug treatment services in Australia annual report shows that almost 1 in 3 (32%) clients were aged between 10 and 29 years in 2022–23, down from 41% in 2013–14 (AIHW 2024a, Table SC.3). For clients seeking treatment for their own drug use, almost 1 in 10 (9.3%) were aged 10–19 and almost 1 in 4 (23%) were 20–29 (AIHW 2024a, Table SC.3).

In 2022–23, among clients who received treatment for their own alcohol or other drug use:

- cannabis was the most common principal drug of concern for clients aged 10–19 (64% of clients), followed by alcohol (14%) (AIHW 2024a, Table SC.10)

- cannabis was also the most common principal drug of concern for clients aged 20–29 (30%), followed by alcohol (28%) (AIHW 2024a, Table SC.10)

- counselling was the most common main treatment type for clients aged 10–19 (49% of clients) and those aged 20–29 (43%). For clients aged 10–19, the second most common main treatment type was support and case management (22%); for those aged 20–29 it was assessment only (24%) (AIHW 2024a, Table SC.19).

A study of the overlap between youth justice supervision and alcohol and other drug (AOD) treatment services from 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2016 showed that young people aged 10–17 who received an alcohol and other drug treatment service were 30 times as likely as the Australian population to be under youth justice supervision (21% compared with 0.7%) (AIHW 2018b).

Dual service clients of AOD treatment service and youth justice supervision were more likely than those who only received AOD treatment services to have multiple treatment episodes (47% compared with 19%) and principal drugs of concern (20% compared with 4%) (AIHW 2018b).

ABS (2018) Deaths Due to Harmful Alcohol Consumption in Australia. ABS cat no. 3303.0. Canberra: ABS, accessed 22 November 2022.

ABS (2022) Alcohol Consumption: 2020-21 financial year. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 25 March 2022

ABS (2023a) Causes of Death, Australia, 2022. ABS cat. no. 3303.0. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 19 October 2023.

ABS (2023b) National, state and territory population. ABS Website. Accessed 8 February 2024.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2018a) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adolescent and youth health and wellbeing. Cat. no. IHW 202. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW (2018b) Overlap between youth justice supervision and alcohol and other drug treatment services: 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2016. Cat. no. JUV 126. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 16 October 2018.

AIHW (2021) Australian Burden of Disease Study: Impact and causes of illness and death in Australia 2018, AIHW, Australian Government. doi:10.25816/5ps1-j259

AIHW (2024a) Alcohol and other drug treatment services in Australia annual report. AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 14 June 2024.

AIHW (2024a) Alcohol and other drug treatment services in Australia: early insights. AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 16 April 2024.

AIHW (2024b) National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2022–2023. AIHW, accessed 29 February 2024.

Chrzanowska A, Man N, Sutherland R, Degenhardt L and Peacock A (2024) Trends in overdose and other drug-induced deaths in Australia, 2003–2022, National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, UNSW Sydney, accessed 28 May 2024.

Lam T, Lenton S, Chikritzhs T, Gilmore W, Liang W, Pandzic et al. (2017) Young Australians’ Alcohol Reporting System (YAARS): National Report 2016/17. National Drug Research Institute, Curtin University, Perth, Western Australia.

National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) (2020) Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol. Canberra: NHMRC. Viewed 30 January 2023.

Scully M, Bain E, Koh I, Wakefield M & Durkin S (2023a) ASSAD 2022/2023: Australian secondary school students’ use of tobacco and e-cigarettes. Cancer Council Victoria. Accessed 22 February 2023.

Scully M, Koh I, Bain E, Wakefield M & Durkin S (2023b) ASSAD 2022-2023: Australian secondary school students’ use of alcohol and other substances. Cancer Council Victoria. Accessed 22 February 2024.

Wilkins R, Vera-Toscano E and Botha F (2024) The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey: Selected Findings from Waves 1 to 21, Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic & Social Research, the University of Melbourne. Accessed 16 May 2024.