People in contact with the criminal justice system

Key findings

View the People in contact with criminal justice systems fact sheet >

The criminal justice system comprises 3 parts, the police (investigative element), courts (adjudicative element) and correctional services (corrective element). Information on alcohol and other drug use from each section of the criminal justice system is presented below.

Police

Data from Recorded Crime – Offenders, found that 15% of offenders had a principal offence that was illicit drug related in 2022–23. Additionally:

- Illicit drug offences (52,315 offenders) were the second most common principal offence nationally, behind acts intended to cause injury (83,926 offenders).

- The number of illicit drug offences increased by 2.7% (up 1,395 offenders) between 2021–22 and 2022–23, the first increase since 2015–16 (ABS 2024c, Table 1).

Among those aged 18 and over, the offender rate remained stable between 2022–23 (238.0 per 100,000 persons) and 2021–22 (235.0 per 100,000 persons) (ABS 2024c, Table 4).

In 2022–23, the number of principal youth offender illicit drug offences (3,380) decreased by 3.5% from 2021–22 (3,503 offences). This is the lowest recorded number since 2008-09 and the eighth consecutive decrease (ABS 2024c).

Courts

Data from Criminal Courts, Australia for 2022–2023 showed that, excluding transfers to other court levels, most defendants had their offences finalised in the Magistrates’ Courts (92%, or 491,671).

- Illicit drug offences were the 3rd most common principal offence, accounting for 7.7% (37,786) defendants finalised in the Magistrates’ Courts. Of these:

- over 2 in 3 (69%, or 26,195 defendants) were possession or use offences (ABS 2024a, Table 1).

- almost three-quarters (74%, or 27,951) of defendants were male (ABS 2024a, Table 3).

- Excluding transfers, illicit drug offences remained steady from 2010–11 to 2018–19. The number of illicit drug offences has been variable between 2018–19 and 2022–23 (37,786 in 2022–23, a decrease from 38,959 in 2021–22) (ABS 2024a, Table 1).

- Of defendants proven guilty in the Magistrates’ Courts for a principal offence of illicit drug offences (35,186 defendants), about 3 in 5 (59%, or 20,935) were sentenced to fines. A further 15% were given a good behaviour order and 3.8% were sent to a correctional institution (ABS 2024a, Table 10).

Corrective services

A snapshot of the adult (aged 18 and over) prison population at 30 June 2023 showed there were 41,929 prisoners in Australia. This represents 202 prisoners per 100,000 adult population and is a 3% increase from 2022 (ABS 2024b).

Young people under youth justice supervision

On an average day in 2022–23, 4,542 young people aged 10 and over were under youth justice supervision. A total of 9,157 young people were supervised at some time during the year, up from 9,031 in 2021–22 (AIHW 2024c). On an average day in 2022–23, more than 4 in 5 (82%) of young people under supervision were supervised in the community. However, around 1 in 5 (18%) were in detention. Some young people may have moved between community supervision and detention on the same day.

In 2021–22, the youth justice supervision data from this period coincides with the presence of COVID-19 in Australia and related social restrictions. Further research is required to better understand the impact of COVID-19 on youth justice supervision (AIHW 2024c).

From 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2016, young people aged 10–17 under youth justice supervision were 30 times as likely as the Australian population of the same age to receive alcohol and other drug (AOD) treatment from publicly funded AOD treatment services (AIHW 2018).

Tobacco smoking

The National Tobacco Strategy 2023–2030 recognises that people in prison have higher rates of tobacco use than the general population and recommends enhanced cessation support for people in prison and those recently released from prison (DHAC 2023).

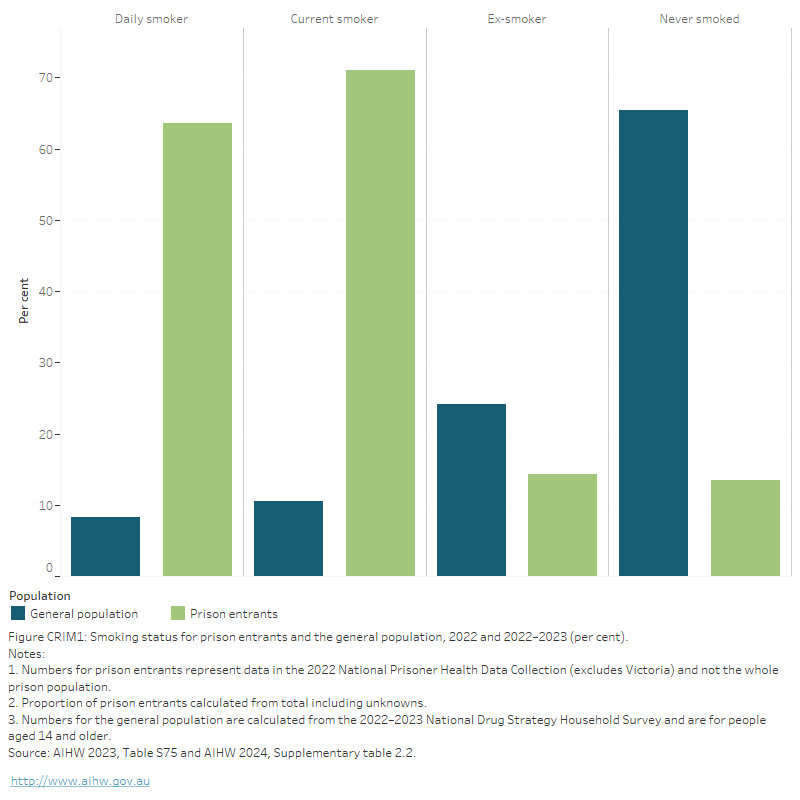

Data from the National Prisoner Health Data Collection (NPHDC) showed that rates of smoking among people in prison are much higher than in the general community. In 2022:

- Almost three-quarters (71%) of prison entrants currently smoked tobacco.

- Nearly two-thirds (64%) of prison entrants smoked tobacco daily (Figure CRIM 1).

- The average age a prison entrant smoked their first full cigarette was 14.2 years (AIHW 2023b).

In the general population, findings from the 2022–2023 National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS) showed that of people aged 14 and over:

- 11% currently smoked.

- 8.3% smoked on a daily basis.

- The average age a person smoked their first full cigarette was 16.6 years (AIHW 2024b, Table 2.17).

Figure CRIM 1: Smoking status for prison entrants and the general population, 2018 and 2022–2023 (per cent)

This figure shows that 71% of prison entrants reported being a current smoker in 2022, and 64% reported being a daily smoker. These are higher proportions than for the general population, where 14.0% of people were current smokers and 11.0% were daily smokers in 2019. Conversely, prison entrants were less likely than the general population to be ex-smokers (14.3% compared with 22.8%) or never smokers (13.5% compared with 63.1%).

View data tables >

Alcohol consumption

The risky consumption of alcohol has been found to be strongly associated with adverse outcomes including criminal offending (Fergusson, Boden & Horwood 2013).

The Drug Use Monitoring in Australia (DUMA) program is an ongoing monitoring program that captures information on illicit drug use among police detainees. Data from the 2021 DUMA indicate that alcohol consumption is common among police detainees.

- Over one in 4 (27%) police detainees reported consuming alcohol in the 24 hours prior to their arrest, with a median of 10 standard drinks consumed.

- Among those who reported drinking alcohol in the 30 days before interview, 3 in 10 (30%) reported that alcohol use contributed to their arrest (Voce & Sullivan 2022).

Prison entrants in 2022 were as likely as the general population to be non-drinkers, however those that did drink were more likely than people in the general community to drink at high risk levels (refer to Box CRIM 1 for information on how alcohol related harm is calculated for prison entrants). Specifically:

- Prison entrants aged 25–34 years were almost 3 times as likely to consume alcohol in greater quantities (7 or more standard drinks on a usual day of drinking) than those in the general community of the same age (39% compared to 13%).

- Almost half (47%) of prison entrants consumed 5 or more standard drinks on a typical day of drinking compared to 18% of people aged 15 and over in the general community.

- During the 12 months prior to prison, 44% of prison entrants consumed alcohol at levels that placed them at high risk of alcohol-related harm (AIHW 2023).

Box CRIM 1: Calculating alcohol-related harm for prison entrants

The proportion of prison entrants who are at risk of alcohol-related harm is determined using questions on alcohol consumption from the WHO’s Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT-C) screening instrument. The AUDIT-C tool alcohol harm risk profile does not align with the alcohol risk guidelines and as such the results may not be directly comparable to the general population (AIHW 2023).

Illicit drugs

It is commonly understood that there is a link between the use of illicit drugs and involvement in the criminal justice system. Illicit drug use has been identified as a primary motivating factor in non-violent property offences such as burglary and theft (Kopak & Hoffman 2014).

The Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission (ACIC) collects national illicit drug arrest data annually from federal, state and territory police services to inform the Illicit Drug Data Report (IDDR). According to the 2020–21 IDDR, there were 140,624 national illicit drug arrests in 2020–21, a decrease from 166,321 arrests in 2019–20. The number of national illicit drug arrests has increased 51% over the last decade (from 93,148 arrests in 2011–12) (ACIC 2023). Most (87%) of the national illicit drug arrests in 2020–21 were for consumer related offences (Figure CRIM 2).

The Prisoners in Australia report contains annual national information on prisoners in custody as at 30 June 2023:

- Prisoners with an illicit drug offence declined between 2022 and 2023 for both males (a decrease of 15%, or 233 prisoners) and females (a decrease of 11%, or 67 prisoners).

- Over the period 30 June 2022 to 30 June 2023, unsentenced prisoners increased by 7% (1,073 offenders) to 15,937. Among unsentenced prisoners, illicit drug offences fell by 2.2% (42 offenders), down to 1,893 offenders (ABS 2024).

Figure CRIM 2: Consumer, provider or total national illicit drug arrests, by drug type, 2010–11 to 2020–21

This figure shows that in 2020–21, most consumer arrests were for cannabis (66,285) followed by amphetamine-type stimulants (35,885).

Information related to criminal activity and contact with the criminal justice system is collected as part of the Ecstasy and Related Drugs Reporting System (EDRS) for people who regularly use ecstasy or other stimulants and the Illicit Drug Reporting System (IDRS) for people who regularly inject drugs.

Of the 2023 EDRS participants:

- 7% had been arrested in the past year.

- The most common self-reported crimes in the last month included drug dealing (24%) and property crime (18%).

- A minor proportion (5%) of the sample reported a lifetime prison history, stable from 2021 (6%) (Sutherland et al. 2023a).

Of the 2023 IDRS participants:

- 24% reported having been arrested in the 12 months preceding interview, stable relative to 2022 (23%).

- 3 in 5 (60%) participants reported a lifetime prison history, remaining stable to 2022 (60%).

- The most common crimes reported in the last month were property crime (24%) and selling drugs for cash profit (21%) (Sutherland et al. 2023b; Figure 40).

Changes due to the impacts of COVID-19 resulted in EDRS and IDRS interviews in 2020–2023 being delivered face-to-face as well as via telephone and videoconference. All interviews prior to 2020 were delivered face-to-face, this change in methodology should be considered when comparing data from the 2020–2023 samples relative to previous years.

Data from the DUMA program indicate that drug use is common among police detainees. In 2021, 45% of police detainees had used cannabis in the past 30 days and 41% had used methamphetamine (Voce & Sullivan 2022).

Among police detainees who provided a urine sample:

- Almost 4 in 5 (77%) tested positive to any drug, and 41% tested positive to more than one drug type.

- The most commonly detected drugs were amphetamine-type stimulants (52% of detainees), cannabis (45%) and opioids (18%) (Voce & Sullivan 2022; Figure CRIM 3).

In 2021, data collection was suspended during quarter 3 and the Sydney collection was relocated from Bankstown to Surry Hills in quarter 4 due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. This should be considered when comparing 2021 data with previous years.

The health of people in Australia’s prisons 2022 reports that overall, three-quarters (73%) of prison entrants reported using illicit drugs in the 12 months before incarceration, with the most common drug being cannabis (53%) followed by methamphetamine (46%) (Figure CRIM 3) (AIHW 2023, Table S86).

In contrast, rates of drug use among the general population were substantially lower, with 1 in 6 (17.9%) people aged 14 and over reporting the use of any illicit drug in the past 12 months (AIHW 2024b, Table 5.6).

Figure CRIM 3: Recent drug use among police detainees (2021) or prison entrants (2022), by drug type (percent)

The figure shows that, in 2021, 77% of police detainees in the Drug Use Monitoring in Australia collection tested positive for any drug via urinalysis. Methamphetamine was the most common drug in positive urine tests (50% of detainees), followed by cannabis (45%), heroin (8%), and cocaine (2%).

View data tables >

Cannabis

Data from the 2020–21 IDDR found that:

- There were 66,285 national cannabis arrests in 2020–21, with the number of arrests increasing 9% over the last decade (61,011 in 2011–12).

- Cannabis (47%) accounted for the greatest proportion of national illicit drug arrests in 2020–21 and most of these arrests (90%) were consumer arrests.

- While cannabis continues to account for the greatest proportion of national illicit drug arrests, this proportion has decreased over the last decade (down from 65% in 2011–12) (ACIC 2023).

Data from the DUMA found that over 2 in 5 (45%) of police detainees reported using cannabis in the past 30 days in 2021 (Voce & Sullivan 2022). In 2021, data were not collected during Quarter 3 and the Sydney collection was relocated from Bankstown to Surry Hills in Quarter 4 due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Amphetamines and other stimulants

Data from the 2020–21 IDDR found that:

- Amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS) accounted for the second largest proportion (26%) of national illicit drug arrests in 2020–21.

- The proportion of arrests attributed to ATS has increased over the last decade (from 18% in 2011–12).

- The number of national cocaine arrests has increased 499% over the last decade, from 995 in 2011–12 to a record 5,958 in 2020–21 (ACIC 2023).

Urinalysis data from the DUMA showed that, in 2021:

- Over half (52%) of police detainees tested positive to amphetamine-type stimulants.

- Almost all (95%) detainees who tested positive to amphetamine-type stimulants tested positive to methamphetamine specifically.

- Small proportions of detainees tested positive to cocaine (2%) and less than 1 percent detections for MDMA (Voce & Sullivan 2022).

Data for 2021 were not collected during Quarter 3 and the Sydney collection was relocated from Bankstown to Surry Hills in Quarter 4 due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. This should be considered when comparing 2021 data with previous years.

Opioids, including heroin

Data from the 2020–21 IDDR found that:

- Heroin and other opioids accounted for 2.0% of national illicit drug arrests in 2020–21.

- The proportion of arrests attributed to heroin and other opioids has decreased over the last decade (from 2.9% in 2011–12) (ACIC 2023).

Urinalysis data from the DUMA found that almost 1 in 5 (18%) police detainees tested positive to opioids in 2021 (Figure CRIM3). This included heroin (4% of detainees), buprenorphine (11%), methadone (2%), and other (unidentified) opioids (4%). Urinalysis screening cannot distinguish non-medical use of pharmaceutical opioids (buprenorphine, methadone).

Data for 2021 were not collected during Quarter 3 and the Sydney collection was relocated from Bankstown to Surry Hills in Quarter 4 due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. This should be considered when comparing 2021 data with previous years.

Health and harms

The NPHDC includes a number of indicators regarding prisoner health and harms. In 2022:

- 51% of prison entrants had ever been told by a health professional that they have a mental health or behavioural condition (including drug and alcohol misuse).

- 11% of prison entrants experienced ‘a lot’ of distress due to alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs, while 31% experienced ‘a little’ distress (AIHW 2023).

Around 1 in 8 (13%) prison dischargees reported using a needle or other injecting, tattooing or piercing equipment that had been used by someone else, while in prison (AIHW 2023). Similarly, earlier data from the National Prison Entrants’ Blood Borne Virus and Risk Behaviour Survey in 2013 found that almost 1 in 5 (18%) prison entrants had shared injecting drug equipment in the previous month, placing them at risk of communicable disease (Kopak & Hoffman 2014 as cited in AIHW 2015).

Treatment

The Alcohol and Other Drug Treatment Services National Minimum Data Set (AODTS NMDS) provides information on treatment provided to clients by publicly funded AOD treatment services, including government and non-government organisations. Data collected for the AODTS NMDS are released twice each year, via an early insights report in April and a detailed annual report mid-year. Information on treatment referral source is not included in the early insights report.

The latest Alcohol and other drug treatment services in Australia annual report shows that diversion referrals into treatment have fallen from 16% in 2013–14 to 8.4% in 2022–23 (AIHW 2024a, Table Trt.11).

The 2022 NPHDC found that opioid substitution treatment (OST) was currently being undertaken by 12% of prison entrants and 7% of prison dischargees. Around 1 in 6 (16%) prison entrants reported ever having been on an OST (AIHW 2023).

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2024a) Criminal Courts, Australia 2022–23 . Canberra: ABS, accessed 15 March 2024.

ABS (2024b) Prisoners in Australia, 2023. Canberra: ABS, accessed 20 March 2023.

ABS (2024c) Recorded Crime – Offenders, 2022-23. Canberra: ABS, accessed 7 March 2024.

ACIC (Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission) (2023) Illicit Drug Data Report 2020–2021 Canberra: ACIC, accessed 24 October 2023.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2015) The health of Australia’s prisoners 2015. Cat. no. PHE 207. Canberra: AIHW, accessed 2 February 2018.

AIHW (2018) Overlap between youth justice supervision and alcohol and other drug treatment services: 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2016, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 14 June 2024.

AIHW (2023) The health of people in Australia’s prisons 2022. AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 15 November 2023.

AIHW (2024a) Alcohol and other drug treatment services in Australia annual report, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 21 June 2024.

AIHW (2024b) National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2022–2023. AIHW, accessed 13 February 2024.

AIHW (2024c) Youth justice in Australia 2022–23, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 04 April 2024.

DHAC (Department of Health and Aged Care) (2023) National Tobacco Strategy 2023-2030. DHAC, accessed 3 May 2023.

Fergusson DM, Boden JM & Horwood LJ (2013) Alcohol misuse and psychosocial outcomes in young adulthood. Result from a longitudinal birth cohort studied to age 30. Drug and alcohol dependence 133:513-9.

Kopak AM & Hoffman NG (2014) Pathways between substance use, dependence, offense type, and offense severity. Criminal Justice Policy Review. 25(6): 743:760.

Sutherland R, Karlsson A, King C, Uporova J, Chandrasena U, Jones F, Gibbs D, Price O, Dietze P, Lenton S, Salom C, Bruno R, Wilson J, Grigg J, Daly C, Thomas N, Radke S, Stafford L, Degenhardt L, Farrell M, & Peacock A (2023a) Australian Drug Trends 2023: Key Findings from the National Ecstasy and Related Drugs Reporting System (EDRS) Interviews. Sydney: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, UNSW Sydney. Accessed 25 October 2023.

Sutherland R, Uporova J, King C, Chandrasena U, Karlsson A, Jones F, Gibbs D, Price O, Dietze P, Lenton S, Salom C, Bruno R, Wilson J, Agramunt S, Daly C, Thomas N, Radke S, Stafford L, Degenhardt L, Farrell M, & Peacock A (2023b) Australian Drug Trends 2023: Key Findings from the National Illicit Drug Reporting System (IDRS) Interviews. Sydney: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, UNSW Sydney. Accessed 25 October 2023.

Voce A & Sullivan T (2022) Drug use monitoring in Australia: Drug use among police detainees, 2021. Statistical Report 40. Australian Institute of Criminology, accessed 6 May 2022.