Early learning: reading to children

Key findings

- In 2017, almost 4 in 5 children aged 0–2 (738,000 or 79%) were regularly read to or told stories by a parent (on 3 or more days in the previous week).

- In 2017, 44% of children age 0–2 had between 25 and under 100 children’s books in the home.

Language is central to human development and is especially important for reading development with long-term consequences for later social and academic functioning (Dickinson et al. 2012). Early home learning experiences in the first 3 years of life are important as for most children, the home is the main influence on child language and cognitive development (Yu & Daraganova 2015).

Reading regularly with children from a young age stimulates patterns of brain development and strengthens parent-child relationships. This, in turn, builds language, literacy, and social-emotional skills (Council on Early Childhood 2014). There is evidence that children begin to benefit from regular reading as early as 8 months (Dickinson et al. 2012). A review of the literature on shared reading found there were increases in the child’s:

- oral language

- vocabulary

- understanding of the conventions of print

- phonological awareness

- alphabet knowledge (Shoghi et al. 2013).

Quality, frequency and length of reading are also important.

Dialogic reading involves elaborating on a story by asking questions throughout the reading activity to create a conversation with the child about the story. This type of reading has stronger effects on children’s oral language skills than traditional shared reading where the child’s engagement in the reading activity is not as explicitly directed (Shoghi et al. 2013).

Frequency of reading to children has been associated with children’s greater vocabulary and higher cognitive ability at 14, 24 and 36 months of age (Raikes et al. 2006). Research using the LSAC found that children whose parents read to them every day when they were 2–3 year olds had higher Year 3 NAPLAN reading scores on average, than children whose parents read to them less frequently. The difference remained significant after accounting for socio-demographic factors (Yu & Daraganova 2015).

Having more than 30 children’s books at home when children were aged 2–3 was positively related to higher NAPLAN scores in reading and numeracy in Year 3. The difference remained significant after adjusting for socio-demographic factors (Yu & Daraganova 2015).

While the effects of shared reading on early literacy are well researched, other activities can also help develop emergent literary skills, including:

- singing

- nursery rhymes

- conversations

- oral storytelling

- environmental print (for example, written printed materials in the general environment such as street signs, food labels, billboards)

- use of digital media (for example mobile devices, smart phones, tablets) (Shoghi et al. 2013).

Box 1: Data sources for reading to children

Data on reading to children are sourced from the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS) Childhood Education and Care Survey (CEaCS) which has been conducted every 3 years since 1969 and up until 2005 was known as the Child Care Survey. The latest data are for 2017.

The survey includes data on learning activities for children aged 0–8, as well as child care and early childhood education (see Early Childhood Education and Care).

In each selected household, detailed information about child care arrangements and early childhood education was collected for a maximum of 2 children aged 0–12. Information was gathered through interviews with an adult who lived permanently in the selected household and was the child’s parent, stepparent or guardian (ABS 2018a).

How many infants are read to by an adult?

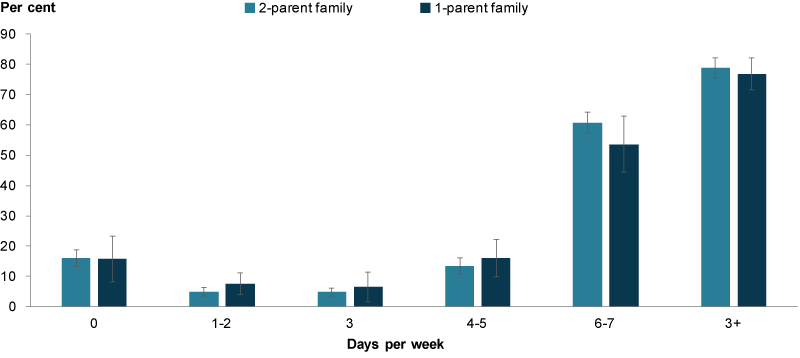

In 2017, almost 4 in 5 children aged 0–2 (738,000 or 79%) were read to or told stories by a parent, on a regular basis in the previous week (that is, on 3 or more days). Around:

- 3 in 5 children (60%) were frequently read to or told stories (that is, on 6–7 days in the previous week)

- 1 in 6 children (16%) were not read to or told stories (Figure 1).

The extent to which parents read to or told stories did not differ depending on type of family:

- 79% of children in 2-parent families and 77% of children in 1-parent families were read to or told stories on a regular basis.

- 17% of children in 2-parent families and 15.7% of children in 1-parent families were not read to or told stories at all

- while children in 2-parent families were more likely to be frequently read to or told stories than children in 1-parent families (61% and 54%, respectively) the difference was not statistically significant.

However, an LSAC study of children aged 2–3 years found a statistically significant result for 2-parent families being more likely to read to their children frequently (61%) than 1-parent families (51%) (Yu & Daraganova 2015).

CEaCS data found that the parent predominantly involved in informal learning at home, which includes reading to children, was female (69%). For around 17% of families, the involvement was shared equally (ABS 2018a).

Figure 1: Number of days where a parent spent time with children aged 0–2 reading or telling stories in previous week, 2017

Note: Relative standard error for 1-parent families for 3 days per week is 39.3% and should be treated with caution.

Chart: AIHW. Source: ABS 2018b.

Have rates changed over time?

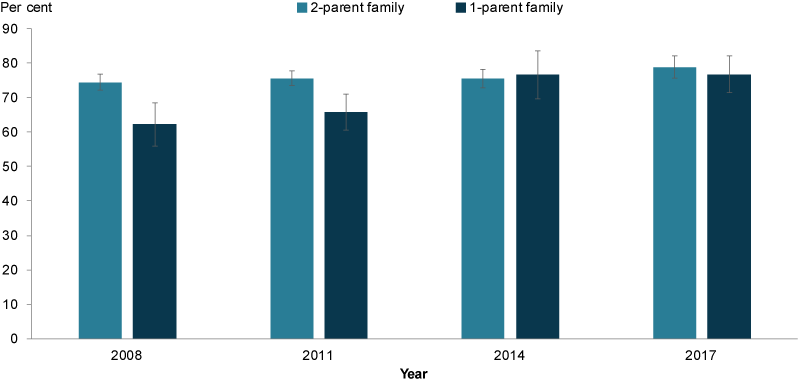

Between 2008 and 2017, the proportion of children read to or told stories regularly in the previous week increased for both children in 2-parent and 1-parent families. The increase for children in 1-parent families was larger (15 percentage points, from 62% to 77%) than for 2-parent families (4 percentage points from 75% to 79%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Children aged 0–2 read to or told stories on 3 or more days in previous week, 2008 to 2017

Chart: AIHW. Source: ABS 2018b.

Are rates of reading to children the same for everyone?

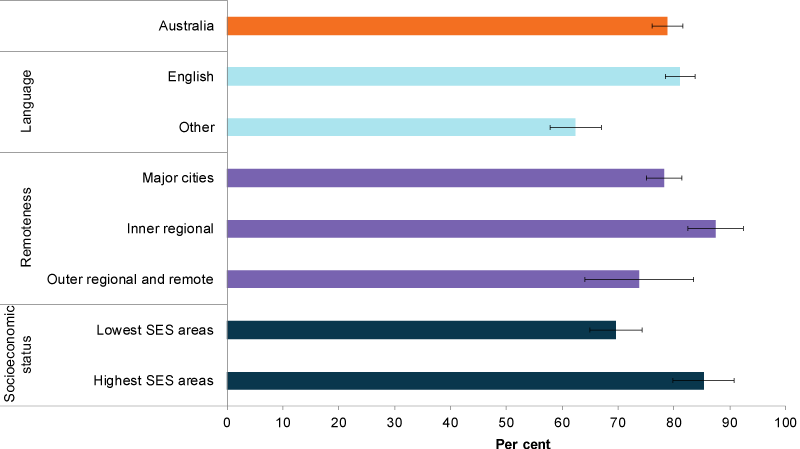

In 2017, the extent to which parents read to or told stories to their children varied by some population groups (Figure 3):

- More parents living in Inner regional (88%) read to children regularly than those in Major cities (78%) and Outer regional and remote combined (74%)

- More parents in the highest socioeconomic areas (85%) read to or told stories on a regular basis than those in the lowest socioeconomic areas (70%).

- The proportion of children in the lowest socioeconomic areas (25%) who were not read to or told stores was more than double that for children in the highest socioeconomic areas (9.8%).

- Fewer children in households where a language other than English was mainly used (62%) were read to or told stories on a regular basis compared to children in households where English was the main language to have been (81%).

Note: In households where English was not the main language spoken at home by the child, the survey does not ask which language was used for reading to child. This means that the language could be English, another language or both. It is possible, however, that respondents have interpreted the question as referring to English.

Figure 3: Children aged 0–2 read to or told stories on 3 or more days in previous week, by population group, 2017

Chart: AIHW. Source: ABS 2018b.

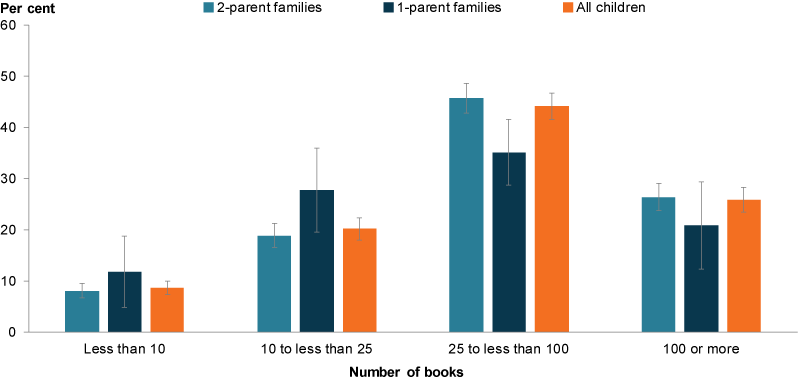

How many books do children have in the home?

In 2017, 44% of children age 0–2 had between 25 and under 100 children’s books in the home. Children from 2-parent families were more likely to have between 25 and under 100 books (46%) than children in 1-parent families (35%).

A higher proportion of children from 1-parent families (28%) had 10 to less than 25 books compared with children from 2-parent families (19%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Number of books in the home for children aged 0–2 by family type, 2017

Chart: AIHW. Source: ABS 2018a.

Data limitations and development opportunities

The current measure of time spent reading or telling stories to children does not account for the time actually spent reading to the child. For example, a parent that spent 2 minutes every day would be classified along with those who spent 2 hours every day. It should also be noted that this measure does not capture children being read to or told stories by adults other than the parent, for example child care workers.

Where do I find more information?

For more information on:

- early learning, see Childhood education and care.

- See also Methods.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2018a. Childhood Education and Care, Australia, June 2017. ABS cat. no. 4402.0. Canberra: ABS.

ABS 2018b. Childhood Education and Care, Australia, June 2017. ABS cat. no. 4402.0. Customised report. Canberra: ABS.

Council on Early Childhood 2014. Policy statement: literacy promotion: an essential component of primary care pediatric practice. Pediatrics 134(2):404–409.

Dickinson D, Griffith J, Golinkoff, R & Hirsh-Pasek K 2012. How reading books fosters language development around the world. Child Development Research. Vol.2012, article ID 602807, 15 pages. doi:10.1155/2012/602807

Raikes H, Pan BA, Luze G, Tamis-LeMonda CS, Brooks-Gunn J, Constantine J et al. 2006. Mother–child book reading in low-income families: correlates and outcomes during the first three years of life. Child Development 77(4):924–53.

Shoghi A, Willersdorf E, Braganza L & McDonald M 2013. Let’s read literature review. Victoria: The Royal Children’s Hospital Centre for Community Child Health, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute.

Yu M & Daraganova G 2015. Children’s early home learning environment and learning outcomes in the early years of school. In The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children Annual statistical report, 63–81. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.