Family economic situation

Key findings

- In 2017–18, there were 489,000 low-income households with children aged 0–14. This represented 24% of all low-income households in Australia.

- In low-income households with children, the average real equivalised disposable income was $558 per week.

- In 2019, around 11% (289,000) of households with children aged 0–14 were jobless families—households with dependent children and no paid employment.

The economic wellbeing of households plays a critical role in the health, education and self-esteem of children. Economic disadvantage in the form of inadequate resources can adversely affect children’s social and educational opportunities, as well as health outcomes in the short and long term (PC 2018; Ryan et al. 2012).

Economic disadvantage encompasses many factors, including low income, material deprivation and social exclusion (PC 2018). These concepts often overlap; however it is possible for a person or family to experience 1 element at a time. Economic disadvantage is also highly dynamic, and most people only experience it for short periods. Only a small proportion of Australians live in ongoing or persistent disadvantage (McLachlan et al. 2013).

For most families, regular adequate income is the single most important determinant of their economic situation. Low income can make a family vulnerable to food insecurity and affect a child’s diet and access to medical care (AIHW 2012; Rosier 2011). Low income can also impact the safety of a child’s environment, the quality and stability of their care, and the provision of appropriate housing, heating and clothing (AIHW 2012; Warren 2017).

This section explores economic disadvantage by focusing on the level and source of household income for households with children aged 0–14.

Box 1: Data source and definitions

Data on household income, sources of income and other characteristics are taken from the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS) Survey of Income and Housing (SIH). The survey collects data about a range of household and personal characteristics such as income levels, income sources, employment status and family composition. These data help provide a richer understanding of the living standards and economic wellbeing of Australians (ABS 2019a).

SIH data can be used to identify and compare households with at least 1 dependent child aged 0–14. Data are collected from residents in private dwellings in Australia (excluding very remote areas) every 2 years, and the latest data are available for 2017–18.

How is income measured?

A household’s access to resources or income can be measured in the form of average weekly equivalised disposable household income. This measure of income is adjusted (or equivalised) according to household size and composition. Equivalising income accounts for larger households needing more resources to achieve the same standard of living as a smaller household. It also allows for comparisons across household types.

To determine the economic wellbeing of children this section focuses on children living in low-income households. These households are defined as those in the 2nd and 3rd income deciles of equivalised household income. Households in the lowest decile are excluded because household income is not always a good measure of the total economic resources available to those with an income close to nil or negative. Some people in the lowest decile may own their homes and have low housing costs, some may be between jobs, or on holiday without pay and some may report negative returns on investments (AIHW 2018).

Data from the SIH are available for Australian households between 2007–08 and 2017–18. Data for all years are expressed in 2017–18 dollars.

How many children live in low-income households?

In 2017–18, according to the SIH, there were 2 million low-income households in Australia. An estimated 24% (or 489,000) of these had dependent children aged 0–14. For these households, the average real equivalised disposable income was $558 per week (ABS 2019a).

Have there been changes over time?

Over the 6 surveys between 2007–08 and 2017–18, the proportion of low-income households with children aged 0–14 decreased from 32% to 24%.

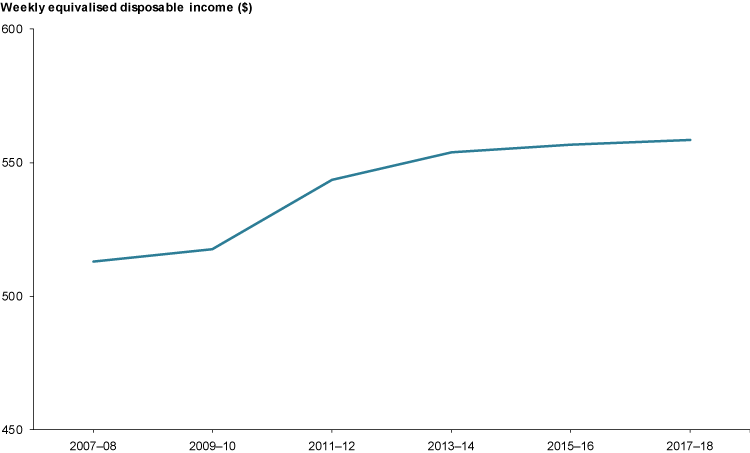

Over the same time, the average weekly real equivalised disposable household income increased from $513 in 2007–08 to $558 in 2017–18 for these households. These increases occurred year-on-year, and are given in real 2017–18 dollars, adjusted for inflation (Figure 1) (ABS 2019a).

Figure 1: Real equivalised household weekly income, households with dependent children aged 0–14 in the 2nd and 3rd income deciles, Australia, 2007–08 to 2017–18

Note: Income is given in 2017–18 dollars, adjusted using changes in the Consumer Price Index.

Chart: AIHW. Source: ABS 2019a.

Does low income vary by population groups?

Among low-income households with children, there were some notable differences in equivalised disposable income according to family types.

In 2017–18, couple-family households had higher average weekly disposable income ($562 per week) compared with multiple family households ($555 per week) and 1-parent family households ($546 per week).

Across remoteness categories, household equivalised disposable income was similar—$560 in Major cities and Inner regional areas and $561 per week in Outer regional and remote areas.

In 2017–18, there was little difference in income between households where the eldest dependent child was aged 0–4 ($565 per week) and those where the eldest dependent child was aged 5–14 ($560 per week) (ABS 2019a).

Overall, disposable household income in low-income households with children aged 0–14 increased for most population groups and household types between 2007–08 and 2017–18. However, in some groups, such as multiple family households and those in Inner regional areas, there was more variation over time (ABS 2019a).

What are the sources of income?

Household income can come from a range of sources, including employment, investments, businesses, government pensions and government allowances.

Government pensions and allowances are administered under the Australian social security system and serve as an important ‘safety net’ to a vast majority of people (Box 2) (Select Committee on Intergenerational Welfare Dependence 2019; Wilkins 2019).

A range of government pensions and allowances are available to support families with their work and family responsibilities. Family Assistance payments (Box 2) are provided to families to assist with the cost of raising children. These payments can provide additional financial assistance to income support recipients (those generally receiving government payments as a primary source of income) and others needing support.

A range of other payments are available recognising the impact that caring for a young child can have on a parent’s capacity to undertake full-time employment, such as:

- Parenting Payment (Single/Partnered)

- Carer Payment

- Carer Allowance

- Carer Supplement.

Box 2: Family Tax Benefit

Family Tax Benefit (FTB) has 2 parts:

- FTB Part A is a per child payment to assist with the cost of raising children (dependent child aged 0–15, or 16–19 in full-time secondary study). A supplement may be paid at the end of the financial year for families with an adjusted taxable income of $80,000 or less. Part A is income tested on family income.

- FTB Part B is a per family payment to single parents, non-parent carers, grandparent carers and families with 1 main income to assist with the cost of raising children. A supplement may be paid at the end of the financial year. Part B is income tested, with single-parent families automatically receiving maximum payment if their income is less than $100,000 (as at 1 July 2015, before that date the income was less than $150,000) (AIHW 2019a).

As at 29 June 2018, 1.4 million Australians were receiving FTB payments, supporting 2.8 million children aged 0–15 (or 16–19 and in full-time secondary study). Of these recipients:

- 77% (1.1 million) received FTB Part A and Part B

- 22% (311,000) FTB Part A only and 1.2% (16,800) Part B only (AIHW 2019a).

Some households with children are also eligible for financial support under the Child Support Scheme. While these payments are not issued by the Australian Government, the Government can facilitate these payments and provide services to assist with child support needs (Box 3).

Box 3: Child support transfers

The Child Support Scheme aims to ensure that children receive an appropriate level of financial support from parents who are separating or are separated. The Department of Human Services provides services to families with children under the age of 18 (or under 19 and in full-time secondary study), such as: child support assessment, registration, collection and disbursement. The department also provides referral services and products to assist with child support needs.

How does child support work?

A person entitled to receive child support payments can elect to transfer child support privately (Private Collect) or ask the department to collect on their behalf (Child Support Collect). In 2017–18, more than half (52%) of cases used Private Collect. Parents are encouraged to manage their child support responsibilities independently; however compliance and enforcement programs to ensure payments are made.

How much child support is transferred between parents?

In 2017–18, $3.6 billion was transferred between parents to support approximately 1.2 million children. Of the $3.6 billion, $1.6 billion was transferred through Child Support Collect, and $2 billion through Private Collect (Department of Human Services 2019).

Reliance on government support

In addition to data on levels of household income, the SIH contains information about sources of income and the proportion contributed by government pensions and allowances. In lower-income households, government pensions and allowances make up a larger proportion of household income than in higher-income households (ABS 2019a). In some households, the proportion of income drawn from government payments is sufficiently high that the household is considered reliant on government support (Box 4).

Box 4: Reliance on government support

Government support refers to pensions, allowances and other payments paid by the government to people under social security and related government programs. These include:

- pensions and allowances that the aged, people with disability, unemployed and sick people receive

- payments for families and children, veterans or their survivors

- study allowances for students (ABS 2019a).

The extent and duration of government support varies across households.

Reliance on government support is defined as having more than 50% of gross household income sourced from government pensions and allowances (AIHW 2019b).

Data from the ABS SIH are available to report on the number of children living in households receiving government support.

Reliance on government support is a cause for policy concern as it is often associated with long-term poverty, social exclusion and other adverse outcomes for recipients and their children (Wilkins 2019). Children living in households receiving a large proportion of income from government pensions and allowances can be vulnerable to long term or entrenched disadvantage. Research has shown that young people aged 18–26 are almost twice as likely to need welfare if their parents have a history of receiving welfare (Cobb-Clark et al. 2017; Select Committee on Intergenerational Welfare Dependence 2019).

How many children live in households reliant on government support?

In 2017–18, 12% (309,000) of households with children aged 0–14 received at least 50% of their gross household income from government pensions and allowances (ABS 2019a).

Does reliance on government support vary by population group?

In 2017–18, the proportion of households reliant on government support payments differed substantially according to family type:

- 47% (181,000) of 1-parent families were reliant on government support

- 5.1% (105,000) of couple families were reliant.

These findings reflect how childrearing responsibilities can limit a person’s ability to gain employment, especially when there are no co-resident parents to share parenting duties (AIHW 2018; McLachlan et al. 2013).

There were also differences in reliance on government support according to remoteness. Households with children in Major cities were less likely reliant on government support than those in Inner regional areas (11% compared with 16%). Further, households in Remote areas were more likely to rely on government support (17%) compared with those in Outer regional (14%) and Inner regional (16%) areas (ABS 2019a).

Have there been changes over time?

Between 2007–08 and 2017–18, the proportion of households with children aged 0–14 reliant on government support remained relatively stable, with small variations over time. This trend was similar among couple families and 1-parent families, and households in Major cities, Inner regional and Outer regional areas (ABS 2019a).

Labour force status

A family’s economic situation is closely related to the labour force status of the individuals within the household.

A person’s labour force status is determined by if they are employed, unemployed or not looking for work (ABS 2016). Parental employment is an important source of income, and often determines the household’s access to resources. Stable employment can also provide financial security, confidence and social contact for parents, with positive effects flowing on to children (PC 2018). In contrast, parental unemployment can have a range of impacts on children’s behaviour, educational attainment and future employment (McLachlan et al. 2013). Children living in jobless families are especially vulnerable across multiple measures of disadvantage (Box 5)

Box 5: What is a jobless family?

Joblessness is a broader categorisation than unemployment and includes those of working age who are not in the labour force for reasons including disability, illness or caring responsibilities (PC 2018). A jobless family is a household with:

- no paid work

- at least 1 dependent child under the age of 15.

Joblessness can increase a family’s risk of disadvantage, reduce social status and constrain engagement in meaningful activities. Australia is reported to have 1 of the highest rates of family joblessness in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (McLachlan et al. 2013).

Data about jobless families in Australia are available from many sources. Estimates vary between sources due to different reporting periods and survey methodologies. Data presented in this section are taken from the ABS Labour Force Status and Other Characteristics of Families publication, produced from the ABS Labour Force, Australia survey. Data may differ from estimates reported using the SIH or HILDA survey.

How many children live in jobless families?

As at June 2019, 11% (289,000 of 2,667,900) of households with children aged 0–14 were jobless households. One-parent families were more likely than couple families to be jobless—37% (194,000) compared with 4.4% (94,800), respectively (ABS 2019c).

These numbers are similar to those at June 2017, when 12% of households with children aged 0–14 were jobless families (5.1% of couple families; 40% of 1-parent families) (ABS 2017).

How does family joblessness affect children?

Family joblessness can affect children by reducing a family’s overall financial security and economic wellbeing. Joblessness denies families an important income stream, and the associated financial constraints can increase financial stress and reduce parental investment in children’s needs such as education, food and housing (Baxter et al. 2011).

Research using the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children has shown that long exposure to family joblessness is associated with poorer cognitive, emotional and physical development outcomes for children (Gray et al. 2011; Gray & Baxter 2012). Further, the negative impacts of joblessness on parenting can be passed onto children who do not learn the skills required to find and retain jobs and may have diminished desire to succeed in education and employment (Baxter et al. 2011). Children in jobless families are significantly more likely living in deprivation across multiple health and wellbeing indicators (Sollis 2019).

For more information on how children in jobless families’ experience deprivation, see Material deprivation.

Data limitations and development opportunities

Income measures assume an equal distribution of resources within households and do not necessarily capture the extent to which economic disadvantage is experienced by children. To overcome these limitations, other measures of disadvantage, such as material deprivation, should be considered in combination. Some data are available, and these are discussed in Material Deprivation.

In addition, disadvantage is highly dynamic and data for this section are taken from a single point. Additional analysis of longitudinal data is required to better understand:

- who is at risk of persistent disadvantage

- how families enter and exit disadvantage

- risk and protective factors.

Longitudinal analysis can also uncover the intergenerational effects of disadvantage, especially how socioeconomic status is passed from parents to children across domains such as wealth, earnings, income, education, health and consumption patterns. Many factors that may be responsible for tying children’s life chances to the family circumstances in which they are born (Cobb Clark et al. 2017).

Where do I find more information?

For more information on:

- the effects of a family’s economic situation on children aged 0–14, see: Children’s Headline Indicators, National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children indicators and Growing up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children.

- government pensions and allowances for families, see: Family assistance payments and Unemployment and parenting income support payments.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2016. Census of Population and Housing: Census Dictionary, 2016. ABS cat. no. 2901.0. Canberra: ABS.

ABS 2017. Labour Force, Australia: Labour force status and other characteristics of families, June 2017. ABS cat. no. 6224.0.55.001. Canberra: ABS.

ABS 2019a. Survey of income and housing, 2017–18. Customised report. Canberra: ABS.

ABS 2019b. Household income and wealth: summary of results, 2017–18. ABS cat. no. 6523.0. Canberra: ABS.

ABS 2019c. Labour Force, Australia: Labour force status and other characteristics of families, June 2019. ABS cat. no. 6224.0.55.001. Canberra: ABS.

AIHW 2012. A picture of Australia’s children 2012. Cat. no. PHE 167. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2018. Children’s Headline Indicators. Cat. no. CWS 64. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2019a. Family assistance payments. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 25 September 2019.

AIHW 2019b. National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children indicators. Cat. no. CWS 62. Canberra: AIHW.

Baxter J 2013. Parents working out work. Australian family trends no. 1. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Viewed 16 July 2019.

Baxter J, Gray M, Hand K & Hayes 2011. Parental joblessness, financial disadvantage and the wellbeing of parents and children. Occasional paper no. 48. Canberra: Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs.

Cobb-Clark DA, Dahmann SC, Salamanca N & Zhu A 2017. Intergenerational disadvantage: learning about equal opportunity from social assistance receipt. IZA (Institute of Labor Economics) discussion paper no. 11070. Bonn: IZA. Viewed 26 September 2019, https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/11070

DHS (Department of Human Services) 2019. 2017–18 Annual report. Canberra: DHS.

Gray M & Baxter J 2012. Family joblessness and child well-being in Australia in Kalil A, Haskins R & Chesters J. Investing in children, work, education, and social policy in two rich countries. Washington D.C: Brookings Institution Press.

Gray M, Taylor M & Edwards B 2011. Unemployment and the wellbeing of children aged 5–10 years. Australian Journal of Labour Economics 14(2):153–72.

McLachlan R, Gilfillan G & Gordon J 2013. Deep and persistent disadvantage in Australia. Productivity Commission staff working paper. Canberra: Productivity Commission.

PC (Productivity Commission) 2018. Rising inequality? A stocktake of the evidence, Commission research paper. Canberra: PC.

Rosier K 2011. Food insecurity in Australia: What is it, who experiences it and how can child and family services support families experiencing it? CAFCA practice paper. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Viewed 16 August 2019.

Ryan RM, Fauth RC & Brooks-Gunn J 2012. Childhood poverty: implications for school readiness and early childhood education. In Saracho ON & Spodek B (Eds.), Handbook of research on the education of young children 3:301–321. New York: Routledge.

Select Committee on Intergenerational Welfare Dependence 2019. Living on the edge. Canberra: Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia.

Sollis K 2019. Measuring child deprivation and opportunity in Australia: applying the NEST framework to develop a measure of deprivation and opportunity for children using the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. Canberra: Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth.

Warren D 2017. Low-income and poverty dynamics: implications for child outcomes. Social policy research paper no. 47. Department of Social Services. Canberra: Department of Social Services. Viewed 1 August 2019.

Wilkins R, Laß I, Butterworth P & Vera-Toscano E 2019. The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey: selected findings, waves 1 to 17. Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research. Melbourne: The University of Melbourne.