Smoking and drinking in pregnancy

Data updates

25/02/22 – In the Data section, updated data related to smoking and drinking in pregnancy are presented in Data tables: Australia’s children 2022 - Health. The web report text was last updated in December 2019.

Key findings

- In 2017 about 1 in 10 (9.5% or about 28,600) women who gave birth reported smoking during the first 20 weeks of their pregnancy.

- The rate of smoking during the first 20 weeks decreased with increasing maternal age up to 35–39 years.

- In 2016, of women who reported they were unaware of being pregnant for a part of their pregnancy, 1 in 2 (49%) drank alcohol before they knew they were pregnant and 1 in 4 (25%) drank after they knew.

Smoking and drinking during pregnancy can increase the risk of poorer outcomes for both mother and baby. These behaviours are known as modifiable risk factors, which means that measures can be made to change them.

Smoking is associated with poorer perinatal outcomes, such as low birthweight, babies who are small for their gestational age at birth, pre-term birth and perinatal death (AIHW 2019a). The risk of SIDS is higher for babies of mothers who smoked during or after pregnancy (WHO 2013). Smoking during pregnancy has also been associated with an increased body mass index (BMI) score among Indigenous children (Thurber et al. 2015).

Mothers who stop smoking during pregnancy reduce the risk of complications during pregnancy and birth, and adverse health outcomes for their baby (AIHW 2019a).

Alcohol use during pregnancy can cause Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder—birth defects and growth and developmental problems—that can persist into adulthood (NHMRC 2009). The risk of harm to the baby is greatest with high, frequent alcohol consumption during the first trimester (12 weeks). The National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) advises that the safest option for women who are pregnant, planning a pregnancy or breastfeeding is to abstain from drinking (NHMRC 2009).

For more information on data used throughout this section, see Box 1.

Box 1: Data sources on smoking and drinking during pregnancy

Data on smoking during pregnancy is sourced from the National Perinatal Data Collection (NPDC). The NPDC is a national population-based, cross-sectional collection of data on pregnancy and childbirth. The data are based on births reported to the perinatal data collection in each state and territory.

Data on drinking during pregnancy are sourced from the National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS) which collects information on alcohol and tobacco consumption, and illicit drug use among the general population in Australia aged 12 or older. It also surveys people's attitudes and perceptions relating to tobacco, alcohol and other drug use. The survey has been conducted every 2 to 3 years since 1985.

How many women smoke during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy?

In 2017, about 1 in 10 (9.5% or about 28,600) women who gave birth reported smoking during the first 20 weeks of their pregnancy, according to data from the AIHW NPDC.

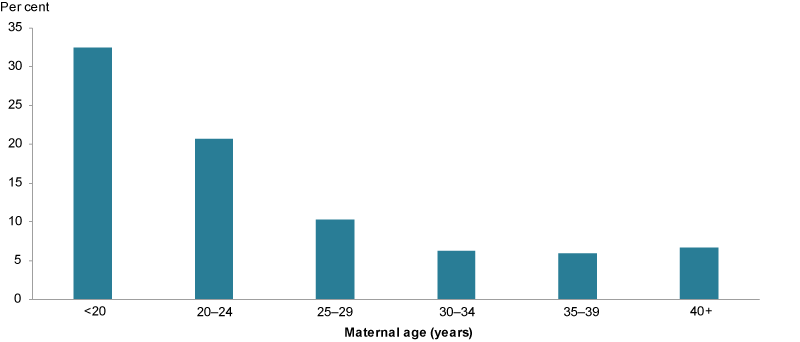

Teenage mothers were the most likely to smoke during the first 20 weeks (1 in 3 or about 32%), and this rate generally decreased with increasing maternal age. Mothers aged 35–39 were the least likely to smoke during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy (1 in 17 or 5.7%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Smoking in pregnancy by age of mother, 2017

Chart: AIHW. Source: AIHW NPDC.

As pregnancy progressed, women were less likely to smoke. In 2017, 7.3% of mothers smoked after the first 20 weeks (AIHW 2019a).

Babies whose mothers smoked at any time during pregnancy were twice as likely to be of low birthweight (less than 2,500 grams) as babies of mothers who did not smoke during pregnancy (13% compared with 6.0%, respectively) (AIHW 2019b).

How many women drink during pregnancy?

In 2016, just over 1 in 3 (about 35%) women aged 14–49 drank during pregnancy. The majority (81%) did so once a month or less frequently—about 1 in 6 (16%) drank 2–4 times a month. The vast majority of women who drank (97%) usually consumed 1–2 standard drinks (AIHW 2017b).

Some women reported they were unaware of being pregnant for a part of their pregnancy. Of these women, 1 in 2 (49%) drank alcohol before they knew they were pregnant and 1 in 4 (25%) drank after they knew.

Have these behaviours changed over time?

Between 2011 and 2017, the proportion of women who smoked during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy fell from 13% to 9.5% (AIHW 2019b).

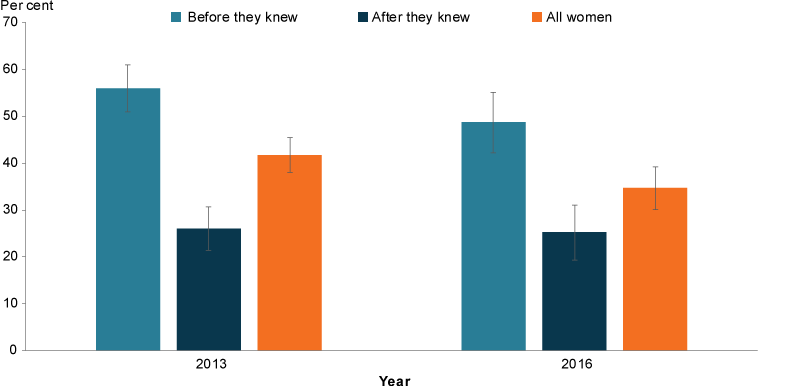

Overall, fewer women aged 14–49 drank during pregnancy in 2016 (35%) than in 2013 (42%). The proportion of women who drank before they knew they were pregnant fell between 2013 (56%) and 2016 (49%), but the result was not statistically significant. The proportion who drank after they knew was similar (26% in 2013 and 25% in 2016) (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Drinking before and after knowing about their pregnancy, women aged 14–49, 2013 and 2016

Chart: AIHW. Source: NDSHS.

How many women use illicit drugs during pregnancy?

In 2016, according to the NDSHS, 2.3% of women used an illicit drug, such as marijuana, ecstasy, cocaine, while pregnant. A slightly lower proportion (1.9%) had used prescription analgesics for non-medical purposes during pregnancy. However, these estimates have high relative standard errors and should be interpreted with caution (AIHW 2017b).

In 2014–15, according to AIHW and Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) analysis of the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey (NATSISS), 4.1% of Indigenous women reported that they used illicit substances during pregnancy. However, this estimate has a high relative standard error and should be interpreted with caution (AIHW 2017a). Note: this rate for Indigenous women is from a different source and so data are not comparable with the NDSHS data cited.

Are these risk factors the same for everyone?

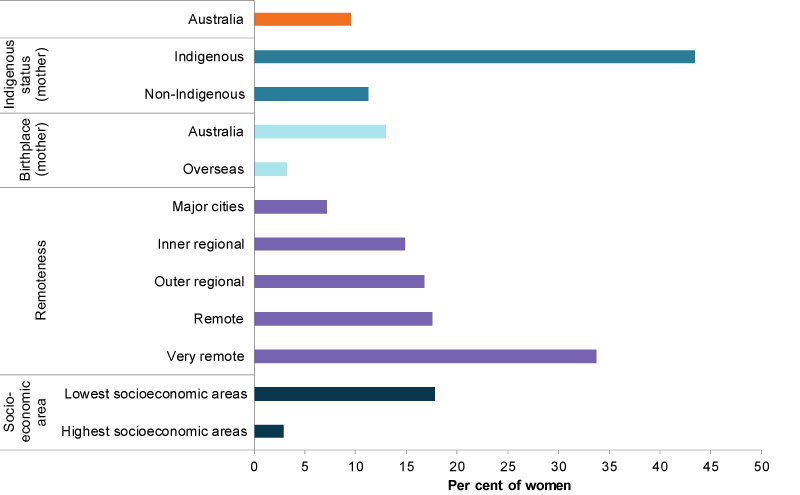

In 2017, the likelihood of a mother smoking during pregnancy differed depending on population group:

- mothers living in Remote (18%) and Very remote (34%) areas had considerably higher rates than mothers living in Major cities (7.2%)

- women living in areas of greater socioeconomic disadvantage were more likely than those living in areas of least disadvantage to smoke (18% and 2.9%, respectively)

- Australian-born mothers had higher rates than mothers born overseas (13% and 3.2%, respectively)

- Indigenous and non-Indigenous mothers varied (age-standardised rates of 43% and 11%, respectively). However, smoking rates during pregnancy among Indigenous women showed a positive change between 2011 and 2016, decreasing by 4 percentage points. See also Indigenous children (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Smoking in pregnancy by selected population groups, 2017

Note: Rates by Indigenous status are age standardised.

Chart: AIHW. Source: AIHW NPDC.

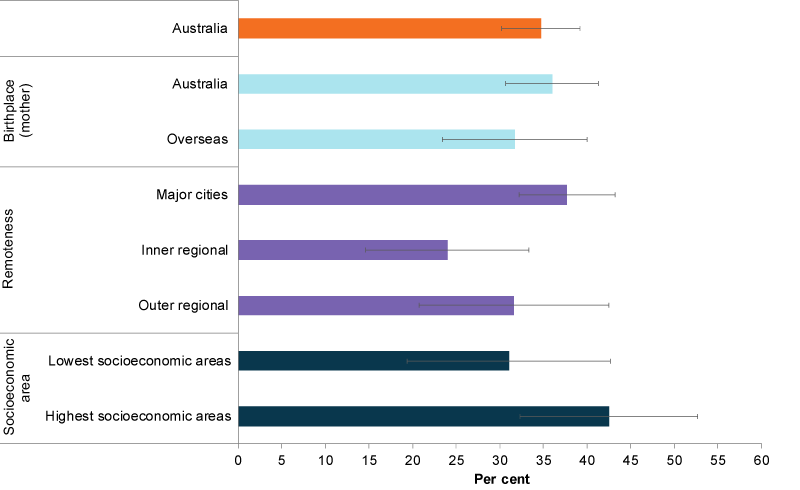

Patterns of drinking were different from those of smoking (Figure 4). Mothers living in Major cities were more likely to drink during pregnancy than those in Inner regional areas (38% compared with 24%, respectively). Note that data are unreliable for Remote and Very remote areas.

There was no statistically significant difference in the likelihood of drinking during pregnancy between mothers living in the highest socioeconomic areas (43%) and those in the lowest (31%).

There was also no statistically significant difference between mothers born in Australia (36%) and mothers born overseas (32%).

Data on Indigenous mothers were available from the NDSHS. However, 2014–15 NATSISS data found that of mothers of children aged 0–3, 10% reported drinking alcohol after finding out they were pregnant (AIHW 2017a). It should be noted that these data are not directly comparable.

Figure 4: Drinking in pregnancy by selected population groups, 2016

Chart: AIHW. Source: NDSHS 2016.

Data limitations and development opportunities

The data on smoking and drinking during pregnancy come from 2 data sources (Box 1) so are not directly comparable. The NPDC is adding alcohol to its collection in 2019–20, with data expected to be available around mid-2022.

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) describes conditions considered to be the result of exposure of an unborn baby to alcohol during pregnancy. These conditions affect the structural and functional development of the brain, structural development of the face, and growth and development generally (AIHW: Bonello et al. 2014). Regular data on FASD are not available for reporting, but surveillance and monitoring have been identified as priorities for determining how many children have FASD, and the rate of new cases occurring.

One option is to enhance the scope of jurisdictional congenital anomalies collections to include FASD, which could then be included in a national congenital anomalies surveillance system, if developed (AIHW: Bonello et al. 2014).

The Royal Commission and Board of Inquiry into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory (Royal Commission) identified FASD as a major problem among young people in the youth justice sector in the Northern Territory (Royal Commission 2017). The Royal Commission also reported a lack of accurate data on the prevalence of FASD in children and young people (Royal Commission 2017).

Some prevalence data are available for Western Australia, where a study of young people in the only youth detention centre in the state identified a high prevalence of FASD (36% of 99 participants) and 88% of participants had at least 1 domain of severe neurodevelopmental impairment (Bower et al. 2018).

Data are available for a range of other antenatal risk and protective factors, as outlined later in this domain. In addition, the AIHW is working with the National Perinatal Data Development Committee to capture family violence in the antenatal period, with the initial focus on recording when screening for family and domestic violence occurred.

Where do I find more information?

For information on:

- smoking during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy for Indigenous mothers, see: Indigenous children

- smoking in pregnancy, see: smoking during pregnancy in Children’s Headline Indicators, Australia’s mothers and babies 2017—in brief Data tables and Healthy community indicators

- drinking and other drug taking during pregnancy, see: Data tables: Chapter 8 specific population groups in National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2016: detailed findings

- antenatal risk and protective factors, such as maternal overweight and obesity, physical activity during pregnancy and antenatal visits, or birth outcomes, see: Australia’s mothers and babies data visualisations, National Core Maternity Indicators data visualisations and Physical activity during pregnancy 2011–12

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2017a. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health performance framework 2017: supplementary online tables. Cat. no. WEB 170. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2017b. National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2016: detailed findings. Drug statistics series no. 31. Cat. no. PHE 214. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2019a. Australia’s mothers and babies 2017—in brief. Perinatal statistics series no. 35. Cat. no. PER 100. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2019b. Australia’s mothers and babies data visualisations. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 25 January 2019.

AIHW: Bonello MR, Hilder L & Sullivan EA 2014. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: strategies to address information gaps. Cat. no. PER 67. Canberra: AIHW.

Bower C, Watkins R, Mutch R, Marriott R, Freeman J, Kippin R et al. 2018. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder and youth justice: a prevalence study among young people sentenced to detention in Western Australia. BMJ Open 2018:8:e019605. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019605.

NHMRC (National Health and Medical Research Council) 2009. Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol. Canberra: NHMRC. Viewed 25 January 2019.

Royal Commission and Board of Inquiry into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory 2017. Volume 1. Viewed 15 August 2019.

Thurber K, Dobbins T, Kirk M, Dance P & Banwell C 2015. Early life predictors of increased body mass index among Indigenous Australian children. PLOS One 10(6):e0130039. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0130039.

WHO (World Health Organization) 2013. WHO recommendations for the prevention and management of tobacco use and second-hand smoke exposure in pregnancy. Geneva: WHO. Viewed 17 May 2019.

National Perinatal Data Collection

- Mother’s tobacco smoking status during pregnancy is self-reported.

- Data includes non-residents, residents of external territories and records where geographic area of usual residence was not stated (with the exception of remoteness and socioeconomic status categories).

- Percentages calculated after excluding records with missing values. Care must be taken when interpreting percentages.

- Indigenous status age-standardised rates are directly age-standardised using the 30 June 2001 Australian female Estimated Resident Population aged 15–44 as the standard population. Five-year age groups are used for age-standardisation, with the exception of the upper age group of 35–44 years. Data presented here are therefore not comparable with data based on different age groups.

- For 2017, Remoteness area derived by applying ABS 2016 Australian Statistical Geography Standard to area of mother’s usual residence.

- For 2017, Socioeconomic status derived by applying ABS 2016 Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas Index of Relative Socio-economic Disadvantage to area of mother's usual residence.

- For more information on data quality, see the National Perinatal Data Collection data quality statement: AIHW METeOR

National Drug Strategy Household Survey, 2016

- The population base is women who, in the previous 12 months, reported a period when they were pregnant but did not know they were pregnant.

- Remoteness categories based on ABS 2011 Australian Statistical Geography Standard.

- Socioeconomic status is based on ABS 2011 Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas Index of Relative Socio-economic Disadvantage.

- For more information on data quality, see the National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2016 data quality statement: AIHW METeOR

For more information, see Methods.