Social and emotional wellbeing

Key findings

- In 2013–14, 1 in 10 children scored in the ‘of concern’ range of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) total difficulties score.

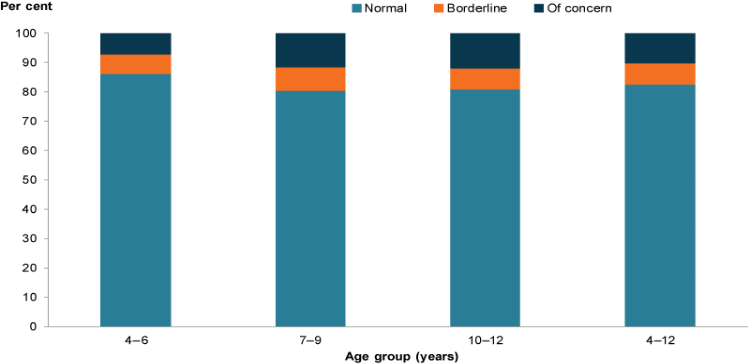

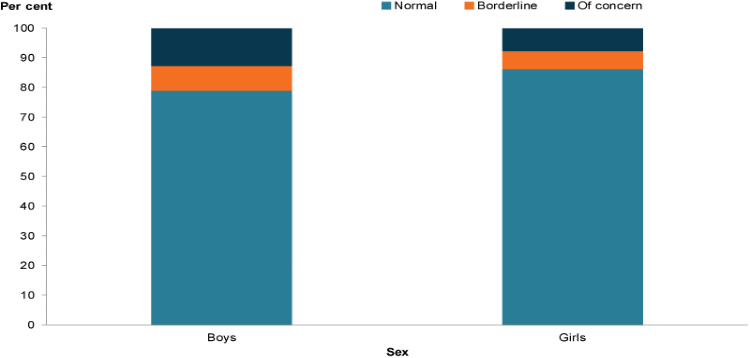

- The proportion of children who scored in the range ‘of concern’ increased with age, from 7.3% for those aged 4–6 to 11.7% for those aged 7–9 and 12% for those aged 10–12.

- Boys were more likely to score in the range ‘of concern’ than girls (12.7% and 7.7%, respectively) (Figure 1).

Good mental health and wellbeing is important to enable children to thrive across the early years and into adolescence and young adulthood. Investing in prevention and early intervention gives children the best opportunity for achieving this (NMHC 2019).

Children’s social and emotional wellbeing (SEWB) is a key component of mental health and wellbeing. It is a complex construct that is sometimes referred to as social and emotional competence, development, learning or literacy.

The emphasis is on behavioural and emotional strengths and ability to adapt and deal with daily challenges (resilience and coping skills) and respond positively to adversity while leading a fulfilling life (AIHW 2012).

An ecological conceptualisation of SEWB recognises that while children’s individual internal characteristics contribute to their social and emotional wellbeing, relationships and interactions with their family, school and community environments have a significant influence (AIHW 2012). A meta-analysis of school-based interventions found that social and emotional skills can be taught at school, and have a positive impact on attitudes, behaviours and academic outcomes (Durlak et al. 2011).

Socially and emotionally competent children:

- are confident

- have good relationships

- communicate well

- do better at school

- take on and persist with challenging tasks

- develop the necessary relationships to succeed in life.

Strong social and emotional competence may also provide resilience against stressors (AIHW 2012).

Cultural background is an important consideration in measurement due to differences in social norms and values between cultural groups (Hamilton & Redmond 2010). For Indigenous children, for example, key elements of SEWB include:

- family and community wellbeing

- connection to ancestry, culture, spirituality and country (Marmor & Harley 2018).

Measuring social and emotional wellbeing

Theories of SEWB development are diverse, and there is little agreement on how best to measure it (Bernard and Stephanou 2017). Positive constructs that measure how well children are thriving in terms of SEWB include the construct of mental health competence, which measures healthy psychosocial functioning (Goldfeld et al. 2014).

How children view their own wellbeing (subjective or self-reported wellbeing), is also important for measuring SEWB. Survey instruments giving children a voice include the South Australian Wellbeing and Engagement collection which measures SEWB for:

- happiness

- optimism

- satisfaction with life

- perseverance

- emotion regulation

- sadness

- worries (SA Department for Education 2018).

Other SEWB instruments include:

- ACER SEW Survey, which includes the domains of feelings and behaviour, internal strengths and values, and external strengths

- Rumble’s Quest, an interactive game allowing primary school children (aged 6–12) to report on their own wellbeing (See Alternate measures for social and emotional wellbeing)

- Behind the News (BtN) which runs 2 large scale Kids’ Happiness surveys for children aged 6–18 and includes data on how often children felt happy, worried and safe (Box 2: How do Australian children rate their own wellbeing? in Introduction).

Currently, these instruments are not being used to collect nationally representative population-level data.

For national reporting in the Children’s Headline Indicators, SEWB is measured as the proportion of children (4–12 years) who scored in the ‘of concern’ range (also referred to as ‘abnormal’) using the SDQ (Box 1).

Box 1: National data on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

Data reported on the SDQ in this section is sourced from the Second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing (2015), also known as the Young Minds Matter survey.

This household survey was conducted in 2013–2014 by the Telethon Kids Institute at the University of Western Australia in partnership with Roy Morgan Research. The survey collected information about the mental health and wellbeing of children and adolescents in Australia, and the extent to which they use health and education services to get help with problems.

The SDQ was originally designed as a screening tool for behavioural problems and mental illness. It incorporates positive and negative attributes through its 5 scales, each of which are relevant to conceptualising SEWB:

- emotional symptoms

- conduct problems

- peer problems

- hyperactivity

- pro-social (AIHW 2012).

While the SDQ has a bias in terms of negative constructs, it has been used extensively as an indicator of SEWB (Hamilton & Redmond 2010). For the purposes of reporting in the Children’s Headline Indicators, it was found to have a sufficiently strong conceptual basis for SEWB, as it assesses individual internal and relational aspects (AIHW 2012).

How many children scored ‘of concern’ on the SDQ?

In 2013–14, 1 in 10 children reported on in the Young Minds Matter survey scored in the ‘of concern’ range of the SDQ total difficulties score. The proportion who scored in the ‘of concern’ range increased with age.

While 7.3% of 4–6 year olds were classified as ‘abnormal’ this increased to 12% of 7–9 year olds and 12% of 10–12 year olds.

Boys (13%) were more likely to score in the range ‘of concern’ than girls (7.7%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Children’s scores on the SDQ, by age, gender, 2013–2014

Chart: AIHW. Source: Second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing 2015.

Is social and emotional wellbeing the same for everyone?

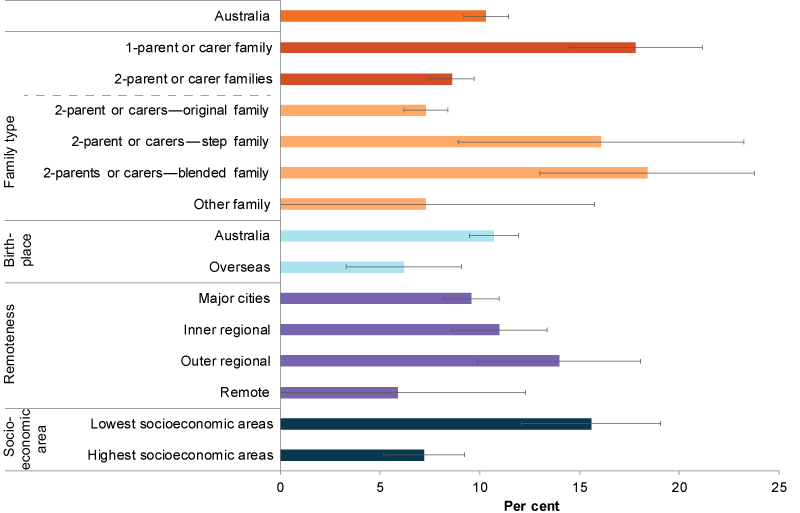

In 2013–14, children living in original 2-parent or 2-carer families were less likely to score ‘of concern’ (8.6%) compared with blended (18%) and 1-parent families (18%). Overseas-born children were also less like to score ‘of concern’ (6.2%) compared to Australian-born children (11%).

Living in the lowest socioeconomic areas was strongly associated with a score ‘of concern’ and double the rate of that for children living in the highest socioeconomic areas (16% and 7.2%, respectively) (Figure 2).

Reliable data are not available on Indigenous children in the Second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. The 2000–2002 Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey found that among children aged 4–17, Indigenous children were 1.6 times as likely than non-Indigenous children to be at risk of social and emotional difficulties based on the SDQ (24% and 15%, respectively) (De Maio et al. 2005).

A comparison of Indigenous and non-Indigenous children aged 6–7 (based on the Longitudinal Survey of Indigenous Children (LSIC), and the Longitudinal Survey of Australian Children (LSAC), respectively) found that Indigenous children tended to have greater levels of social and emotional difficulties using the SDQ (DSS 2015). However, using the SDQ showed that on average Indigenous children in LSIC had higher prosocial scores (a strengths-based measure which includes being considerate, sharing and being helpful and kind) than non-Indigenous children (DSS 2015).

Figure 2: Children scoring ‘of concern’ on the SDQ by selected population groups, 2013–2014

Note: Step family have at least 1 resident stepchild, but no child who is the natural or adopted child of both partners. Blended families have 2 or more children with at least 1 the natural or adopted child of both parents, and at least 1 the stepchild of 1 of them.

Chart: AIHW. Source: Second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing 2015.

Alternate measures for social and emotional wellbeing

Since the SEWB indicator for the Children’s Headline Indicators was developed, there has been growing interest in positive measures of social and emotional wellbeing. Several alternatives have emerged and could potentially inform future national information development and reporting in this area.

An alternative to the SEWB measure using the SDQ is the construct of positive mental health, known as mental health competence. This measures healthy psychosocial functioning. It was developed as a population measure within the framework of the Australian Early Development Census (AEDC) (Goldfeld et al. 2014). The measure is strengths-based and includes 5 positive mental health constructs from the AEDC:

- overall social competence

- responsibility and respect

- approaches to learning

- readiness to explore new things

- prosocial behaviour (Goldfeld et al. 2014).

As the AEDC is conducted every 3 years, there is the opportunity for comparisons over time. One limitation is that it is limited to children age 4–5.

Results from an epidemiological study of positive mental health of children entering school (aged 4–5) and included in the 2012 AEDC cohort, found that mental health competence varied across child population groups (Goldfeld et al. 2017). The study found that:

- Children with good oral communication in the classroom were 19 times as likely to have high mental health competence than children with poor communication skills.

- Children who attended preschool were almost 40% more likely to have high mental health competence than children who had not.

- Boys were more than 50% less likely to have high mental health competence than girls.

- Overall, bilingual children were 16% less likely to have high mental health competence than monolingual children. However, bilingual children with good oral communication were slightly more likely (7%) to have high mental health competence than monolingual children.

- Children living in the highest socioeconomic areas were 60% more likely to have high mental health competence compared with children in the lowest socioeconomic areas (Goldfeld et al. 2017).

For information on the Multiple Strength Indicator, a measure of children’s developmental strengths based on the AEDC, see Box 2 in The transition to primary school.

Another approach to measuring SEWB comes from the Wellbeing and Engagement Collection in South Australia. This collection includes survey data from South Australian middle year students (years 4, 5, 6, 7—aged 9–12) and secondary school (years 8, 9—aged 13–14). Social and emotional wellbeing is defined in terms of 7 constructs:

- happiness

- optimism

- satisfaction with life

- perseverance

- emotion regulation

- sadness

- worries (SA Department for Education 2018).

The 2017 study found that among primary school children:

- Most reported high or medium levels of optimism (86%) and happiness (84%) and low or medium levels of sadness (86%).

- Fewer primary school children reported high or medium levels of perseverance (76%) and low or medium levels of worrying about life (77%) (SA Department for Education 2018).

The ACER SEW Survey is a strengths-based survey based on an ecological conception of social and emotional wellbeing organised into 3 domains:

- feelings and behaviour, both positive and negative

- internal strengths, including social, emotional and learning skills, and values

- external strengths, which includes 3 aspects: community, home and school.

The survey distinguishes between 5 levels of social and emotional wellbeing of young people:

- very highly developed

- highly developed

- developed

- emerging

- low (Bernard & Stephanou 2017).

The survey provides schools with information about their student population (whole school, specific year levels or targeted groups) that can be used to direct planning and problem-solving efforts.

Currently, nationally representative results are not available; however, its feasibility could be explored.

Rumble’s Quest is a recent development in the area of SEWB. It is an interactive game allowing primary school children (aged 6–12) to report on their own wellbeing. Its 4 dimensions of child wellbeing are:

- attachment to school

- self-regulation

- social confidence and positive relationships

- supportive home relationships.

Although there is currently no national data collection based on Rumble’s Quest, its feasibility could be further explored. This would involve looking at:

- expanding uptake

- establishing a nationally representative sample methodology

- developing the required data governance arrangements.

Data limitations and development opportunities?

Currently it is not possible to look at changes over time in Australian children’s SEWB based on the SDQ. The SDQ was not included in the first Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing, and there are currently no plans for it to be repeated.

In recognition that the construct of SEWB has a different meaning for Indigenous children, an additional construct is needed covering relational health of community, culture and country (Marmor & Harley 2018).

Work being undertaken by the National Mental Health Commission on developing the National Children’s Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy will also help inform reporting in this area (NMHC 2019).

Where do I find more information?

For more information on related topics in Australia’s children, see:

- Children’s perspective of wellbeing in Introduction

- Children with mental illness.

For information on:

- social and emotional wellbeing as defined using the SDQ, see: Social & emotional wellbeing in Children’s Headline Indicators and Social and emotional wellbeing: development of a Children’s Headline Indicator.

- SDQ results from the Young Minds Matter survey, see: Young Minds Matter Survey Results Query Tool.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2012. Social and emotional wellbeing: development of a Children’s Headline Indicator. Cat. no. PHE 158. Canberra: AIHW.

Bernard ME & Stephanou A 2017. Ecological levels of social and emotional wellbeing of young people. Child Indicators Research 11(2):661–679. doi: 10.1007/s12187-017-9466-7.

DSS (Department of Social Services) 2015. Footprints in time: the longitudinal study of Indigenous Children—report from Wave 5. Canberra: DHS.

De Maio JA, Zubrick SR, Silburn SR, Lawrence DM, Mitrou FG, Dalby RB et al. 2005. The Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey: measuring the social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal children and intergenerational effects of forced separation. Perth: Curtin University of Technology & Telethon Institute for Child Health Research. Viewed 9 May 2019.

Durlak JA, Weissberg RP, Dymnicki AB, Taylor RD & Schellinger K 2011. The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: a meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development 82(1):405–432.

Goldfeld S, Kvalsvig A, Incledon E & O’Connor M 2017. Epidemiology of positive mental health in a national census of children at school entry. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 71(3):225–231.

Goldfeld S, Kvalsvig A, Incledon E, O’Connor M & Mensah F 2014. Predictors of mental health competence in a population cohort of Australian children. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 68(5):431–437.

Hamilton M & Redmond G 2010. Conceptualisation of social and emotional wellbeing for children and young people, and policy implications. Canberra: ARACY and AIHW.

Marmor A & Harley D 2018. What promotes social and emotional wellbeing in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children? Family Matters no. 100. Melbourne: AIFS. Viewed 20 May 2019.

NMHC (National Mental Health Commission) 2019. National Children’s Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy. Viewed 23 September 2019.

SA (South Australia) Department for Education 2018. Wellbeing and engagement collection: South Australia 2017. Adelaide: SA Department for Education. Viewed 20 May 2019.

Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing, 2015

- Remoteness is based on the 2011 Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS). The survey was not conducted in Very remote areas.

- Socioeconomic status is based on ABS 2011 Socio-Economic Index of Relative Disadvantage.

- The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) is used internationally to measure mental health problems in children and adolescents. It consists of a brief behavioural screening questionnaire comprising five subscales of five items each. Items in four of these subscales, that is emotional problems, conduct problems, hyperactivity and peer problems, are combined to generate a total difficulties score. Scores are assigned a category of 'normal', borderline' and 'abnormal' which are reported here. Scores in the ‘abnormal’ range indicate substantial risk of clinically significant problems. The SDQ was designed so that approximately 10% of children and adolescents will fall into the ‘abnormal’ range on the total difficulties score. The SDQ also includes an impact scale that measures interference in life due to emotional and behavioural problems in the domains of home life, friendships, classroom learning and leisure activities.

- The 'Family composition of household' is classified according to families with two parents or carers and families with one parent of carer. Families with two parents or carers is further split into original, step, blended or other families corresponding to the Australian Bureau of Statistics Family blending classification variable introduced in the 2006 Census. Original families contain at least one child who is the natural, adopted or foster child of both parents in the couple and no step children (the 2006 Census uses the label ‘Intact’ rather than ‘Original’). Step families contain at least one resident step child, but no child who is the natural or adopted child of both parents. Blended families consist of two or more children, where at least one child is the natural or adopted child of both parents, and at least one who is the step child of one of them. Other families consist of no children who are the natural, adopted, foster, or step child of either parent or carer, and include families with children being raised by their grandparents or other relatives.

For more information, see Methods.