Children exposed to family violence

Data updates

25/02/22 – In the Data section, updated data related to children exposed to family violence are presented in Data tables: Australia’s children 2022 – Justice and safety. The web report text was last updated in December 2019.

Key findings

- The 2016 Personal Safety Survey (PSS) estimates that about 1 in 6 women (16% or 1.5 million) and 1 in 9 men (11% or 992,000) experienced physical and/or sexual abuse before the age of 15.

- According to the 2018 ABS Recorded Crime data, more than two-fifths of all sexual assaults recorded against children aged 0–14 (around 3,100) were perpetrated by a family member.

- Sexual assaults perpetrated by family members were almost 4 times more likely perpetrated against girls than boys (107.0 sexual assaults per 100,000 girls compared with 28.3 sexual assaults per 100,000 boys).

- Where the perpetrator was specified, a parent or another family member was the perpetrator in more than half (58%) of assault-related hospitalisations involving children aged 0–14 in 2016–17.

Violence comes in many forms, including:

- family or domestic violence

- sexual and other physical assault

- maltreatment

- bullying

- emotional or psychological abuse (WHO 2016).

A child can be exposed to violence either by:

- directly experiencing the violence (being the target)

- witnessing violence being inflicted upon somebody else (Kulkarni et al. 2011).

When a child is exposed to violence within their family this is considered family violence (AIHW 2019) (Box 1). When children themselves directly experience family violence, the perpetrator is generally the child’s parent/guardian or in a relationship with the child’s parent/guardian, or more broadly speaking a person in a position of trust (AIHW 2018; Campo 2015).

Box 1: Defining family, domestic and sexual violence

Family violence refers to any violence between family members, typically where the perpetrator exercises power and control over another person. This violence can be sexual or non-sexual. Family violence is the preferred term for violence between Indigenous people, as it covers the extended family and kinship relationships in which violence may occur (COAG 2011).

Domestic violence is considered a subset of family violence. It refers to violent behaviour between current or previous intimate partners (AIHW 2019). Sexual violence refers to behaviours of a sexual nature carried out against a person’s will. It can be perpetrated by a current or previous partner, other known people, or strangers.

Being exposed to family violence can have a wide range of detrimental impacts on a child’s development, mental and physical health, housing situation and general wellbeing (AIHW 2019; ANROWS 2018; WHO 2016). More specifically, research has found exposure to family violence is associated with a range of outcomes, including:

- diminished educational attainment

- reduced social participation in early adulthood

- physical and psychological disorders

- suicidal ideation

- behavioural difficulties

- homelessness

- future victimisation and/or violent offending (AIHW 2018; Bland & Shallcross 2015; Campo 2015; De Maio et al. 2013; Holt et al. 2008; Jaffe et al. 2012; Knight 2015).

The impacts of childhood exposure to family violence will be explored as part of the First national study of child abuse and neglect in Australia, being conducted from 2019–2023 (QUT 2019).

When a child is exposed to family violence along with multiple risk factors, such as socioeconomic disadvantage, parental mental ill health, and parental substance abuse, more extreme negative outcomes are likely (Casey et al. 2009; Campo 2015; Fergusson et al. 2006; Fulu et al. 2013).

However, exposure to family violence alone does not mean a child will necessarily experience negative outcomes. With the right support, children exposed to family violence may have increased resilience later in life (Alaggia & Donohue 2018; Campo 2015; Jaffe et al. 2012).

For this section, children who have directly experienced family violence are identified through 2018 Recorded Crime—Victims data and the AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database, where information on the relationship of the perpetrator to the victim are available (Box 1 in Children and crime). These data are a subset of the relevant assault data discussed in Children and crime. Some data from the 2016 ABS PSS on children who witness violence in their home, and adults who experienced family violence as a child, are also included (Box 2).

Often children exposed to family violence may have contact with state and territory child protection systems (see, Child abuse and neglect and Children in non-parental care). While this section focuses on children who have experienced family violence, there are other instances where a child experiences violence, including those described in Children and crime and Bullying.

Box 2: ABS Personal Safety Survey

The ABS 2016 PSS provides national data on the prevalence of violence experienced by women and men. Violence refers to any incident involving the occurrence, attempt or threat of either physical or sexual assault. Where a person has experienced more than 1 type of violence, their experiences are counted separately for each type.

The PSS collected in-depth information from 15,589 women and 5,653 men (21,242 persons in total) aged 18 and over about:

- any violence experienced since the age of 15

- any violence experienced in the 12 months before the survey

- current and previous partner violence and emotional abuse since the age of 15

- stalking since the age of 15

- physical and sexual abuse before the age of 15

- witnessing violence between a parent and partner before the age of 15

- lifetime experience of sexual harassment

- general feelings of safety (ABS 2017).

Children exposed to family violence

The 2016 PSS estimates that about 1 in 6 women (16% or 1.5 million) and 1 in 9 men (11% or 992,000) experienced physical and/or sexual abuse before the age of 15.

Parents were the most common perpetrators of physical abuse before this age. Around 45% of adults experienced physical abuse before the age of 15 by a father or stepfather, and 24% by a mother or stepmother. Where mothers or stepmothers were identified as the perpetrator, victims were more likely their daughters (66%) than their sons (35%) (ABS 2018a).

Of those adults who experienced sexual abuse before the age of 15, nearly 8 in 10 (79%) were abused by a relative, friend, acquaintance or neighbour. A minority were abused by a stranger (11%) (ABS 2018a).

The 2016 PSS also estimated that of those who had experienced violence from a previous partner and had children in their care when the violence occurred, 418,000 women (68%) and 92,200 men (60%) reported that the children had seen or heard the violence.

Police responses

Sexual assault

According to ABS Recorded Crime data, in 2018 around 3,100 sexual assaults against children aged 0–14 were perpetrated by a family member (see Children and crime). This represented more than two-fifths of all sexual assaults recorded against children aged 0–14.

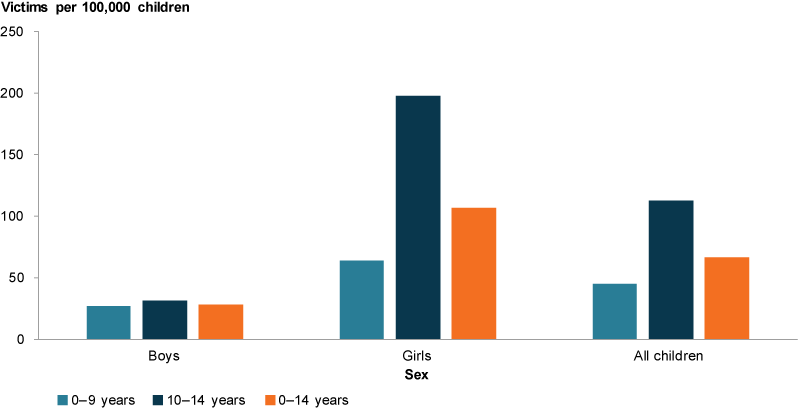

Sexual assaults perpetrated by family members were:

- more likely perpetrated against girls than boys, with a rate of 107.0 sexual assaults per 100,000 girls aged 0–14, compared with 28.3 sexual assaults per 100,000 for boys aged 0–14 (Figure 1)

- highest for girls aged 10–14, with a rate of 197.8 sexual assaults per 100,000.

Rates showed no real variation between 2014 and 2018. This was true for all age and sex groups.

Figure 1: Victims of sexual assault by a family member, by age, 2018

Chart: AIHW. Source: ABS 2019.

Other assault

For the 6 states and territories that had assault data available, around 3,900 assaults against children aged 0–14 in 2018 were considered family violence. More than half of these (55%) were for children aged 10–14. Except for Tasmania, rates of assault for children aged 10–14 were double or more the rates of children aged 0–9 for all states and territories.

The rate of other assaults perpetrated by a family member against children was higher in the Northern Territory than in other states and territories (237.3 assaults per 100,000 children aged 0–14) (Figure 2). Western Australian and Northern Territory had the highest rate of assault perpetrated by a family member against children aged 10–14 years (327.2 assaults per 100,000 children aged 10–14 and 436.8 assaults per 100,000 children, respectively).

Figure 2: Victims of assault by a family member, by jurisdiction and age, 2018

Chart: AIHW. Source: ABS 2019.

Hospitalised cases due to family violence cases

In 2016–17, there were more than 600 hospitalised assault cases of children aged 0–14, including 156 Indigenous children.

For cases where the perpetrator was specified (79%, or 481), nearly:

- 1 in 2 (45%, or 217) children were assaulted by a parent

- 1 in 8 (13%, or 71) by another family member.

For Indigenous children, about 2 in 3 (68%, or 83) assaults were perpetrated by a parent or family member.

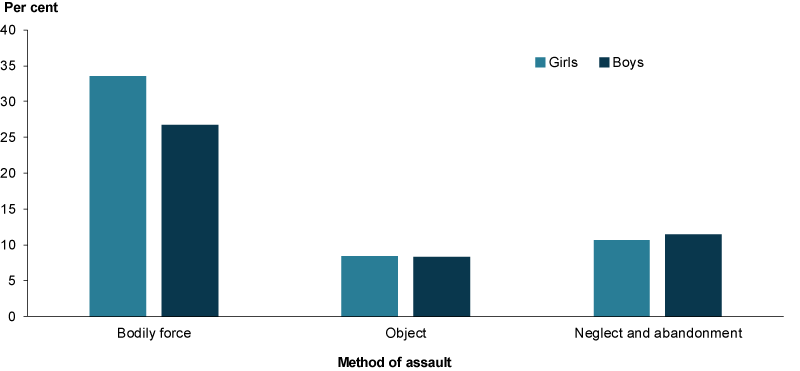

Of the 131 hospitalised assault cases of girls due to family violence:

- 44 (34%) involved assault by bodily force

- 11 (8%) with an object

- 14 (11%) neglect and abandonment by family.

Of the 157 hospitalised assault cases of boys due to family violence:

- 42 (27%) involved assault by bodily force

- 13 (8%) with an object

- 18 (11%) neglect and abandonment by family (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Hospitalised assault cases by a family member, children aged 0–14, by type of assault, by sex, 2016–17

Chart: AIHW. Source: AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database.

Data limitations and development opportunities

It is difficult to obtain complete and robust data on children’s exposure to family violence due to the sensitivity of the subject, with administrative sources only able to identify reported cases and most large-scale population surveys focusing on adult experiences and/or their perceived knowledge of child experiences.

While administrative data collections, such as police and hospital data, can provide some insights, these data sources are likely to underestimate the true extent of children exposed to family violence, with many children (and non-perpetrating parent/guardians) reluctant to report family violence to the police or seek necessary medical attention (ABS 2011; Stoltenborgh et al. 2011, 2013).

To enhance current administrative data on family violence, the identification and collection of data on family violence in other routinely collected administrative data sources is important. Improvements to existing collections, for example child protection, specialist homelessness services, and perinatal, are underway (AIHW 2019).

To supplement administrative data, the First national study of child abuse and neglect in Australia, being conducted from 2019–2023, may provide additional insight into family violence by retrospectively reporting on childhood experiences of family violence for respondents aged 16 and over (QUT 2019). In addition to collecting data on childhood experiences retrospectively, data collected directly from children is also important (see ‘What’s missing’ in Justice and safety).

Where do I find more information?

For more information on:

- children’s exposure to family violence, see: Domestic violence in the National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children

- family, domestic and sexual violence, see: Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia: continuing the national story 2019.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2011. Measuring victims of crime: a guide to using administrative and survey data. ABS cat. no. 4500.0.55.001. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 17 April 2019.

ABS 2017. Personal safety, Australia, 2016 ABS cat. no. 4906.0. Canberra: ABS.

ABS 2018a. Personal Safety Survey, 2016, TableBuilder. ABS cat. no. 4906.0. Findings based on use of ABS TableBuilder data. Canberra: ABS.

ABS 2019. Recorded crime—victims, Australia, 2018. ABS cat. no. 4510.0. Canberra: ABS.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2018. Specialist homelessness services annual report 2017–18. Cat. no. HOU 299. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2019. Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia: continuing the national story. Cat. no. FDV 3. Canberra: AIHW.

Alaggia R & Donohue M 2018. Take these broken wings and learn to fly: applying resilience concepts to practice with children and youth exposed to intimate partner violence. Smith College Studies in Social Work 88(1): 20–38.

ANROWS (Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety) 2018. Research summary: the impacts of domestic and family violence on children. Sydney: ANROWS. Viewed 22 May 2019.

Bland D & Shallcross L 2015. Children who are homeless with their family: a literature review for the Queensland Commissioner for Children and Young People. Brisbane: Queensland University of Technology, Children and Youth Resource Centre. Viewed 22 May 2019.

Campo M 2015. Children’s exposure to domestic and family violence: key issues and responses. Child Family Community Australia (CFCA) paper no. 36. Melbourne: CFCA information exchange, Australian Institute of Family Studies. Viewed 22 May 2019.

Casey E, Beadnell B & Lindhorst T 2009. Predictors of sexually coercive behaviour in a nationally representative sample of adolescent males. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 24(7):1129–1147.

COAG (Council of Australian Governments) 2011. The National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children. Canberra: Department of Social Services.

De Maio J, Kaspiew R, Smart D, Dunstan J & Moore S 2013. Survey of recently separated parents: a study of parents who separated prior to the implementation of the Family Law Amendment (Family Violence and Other Matters) Act 2011. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Viewed 22 May 2019.

Fergusson DM, Boden JM & Horwood LJ 2006. Examining the intergenerational transmission of violence in a New Zealand birth cohort. Child Abuse and Neglect 30(2):89–108.

Fulu E, Warner X, Miedema S, Jewkes R, Roselli T & Lang J 2013. Why do some men use violence against women and how can we prevent it? Quantitative findings from the United Nations Multi-Country Study on Men and Violence in Asia and the Pacific. Bangkok: UNDP, UNFPA, UN Women and UNV. Viewed 22 May 2019.

Holt S, Buckley H & Whelan S 2008. The impact of exposure to domestic violence on children and young people: A review of the literature. Child Abuse and Neglect 32:797–810.

Jaffe P, Wolfe D & Campbell M 2012. Growing up with domestic violence: assessment, intervention, and prevention strategies for children and adolescents. Cambridge: Hogrefe Publishing.

Knight C 2015. Trauma-informed social work practice: Practice considerations and challenges. Clinical Journal of Social Work 43:25–37.

Kulkarni MR, Graham-Bermann S, Rauch SA & Seng J 2011. Witnessing versus experiencing direct violence in childhood as correlates of adulthood PTSD. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 26(6):1264–1281.

QUT (Queensland University of Technology) 2019. First national study of child maltreatment. Brisbane: QUT. Viewed 8 April 2019.

Stoltenborgh M, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van Ijzendoorn MH & Alink LRA 2013. Cultural-geographical differences in the occurrence of child physical abuse? A meta-analysis of global prevalence. International Journal of Psychology 48(2):81–94.

Stoltenborgh M, van Ijzendoorn MH, Euser EM & Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ 2011. A global perspective on child sexual abuse: meta-analysis of prevalence around the world. Child Maltreatment 16(2):79–101.

WHO (World Health Organization) 2016. Violence against children fact sheet. Geneva: WHO. Viewed 1 May 2019.

ABS 2018 Recorded Crime—victims, Australia

- Due to some variability in the interpretation and implementation of the National Crime Recording Standard by jurisdictions in relation to assault, a national rate for victims of assault is not available. For this reason, data are provided for selected jurisdictions only. For more information, see Recorded crime—victims, Australia, 2018.

- Data on victims of recorded crime presented here refers to the age the victim was at the time the crime was recorded by police, and may not reflect the child’s age when the crime occurred.

- ABS Recorded Crime data do not allow for the reporting of Indigenous status for the crimes and age-groups discussed here. This is an important gap, given the over-representation of Indigenous children in the assault hospitalisations.

- Due to changes in police recording of crimes and a revision of offence classification standards, comparisons cannot be made between data presented here and that presented before 2010 in previous publications of A picture of Australia’s children.

AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database

- In admitted patient care data, specific information about a perpetrator may not be available for a number of reasons, including information not being reported by, or on behalf of, victims, or information not being recorded in the patient’s hospital record. The perpetrator of assault was less likely to be specified for male, compared with female victims, and for young or middle-aged adults, compared with child and older victims. Comparisons of the type of perpetrator between sex and age groups, should be made with some caution.

For more information, see Methods.