Introduction

Australia’s children gives a comprehensive overview of the wellbeing of children living in Australia. It brings together the latest available data on a wide range of topics and builds on previous Australian Institute for Health and Welfare (AIHW) reporting about children.

Childhood is an important time for healthy development, learning and establishing the foundation blocks of future wellbeing. It is also a time of vulnerability, during which children have the right to live in safety and be protected from harmful influences and abuse. While a positive start in life helps children to reach their full potential, a poor start increases the chances of adverse outcomes with wide and long-reaching consequences for the individual, society and potentially future generations.

Australia’s children includes information on a range of topics, relevant to each of the 7 domains of the AIHW people-centred data model-health, education, social support, household income and finance, parental employment, housing and justice and safety.

The key national indicators for child health, development and wellbeing, which underpinned the report series, A picture of Australia’s children form the basis of Australia’s children. The Children’s Headline Indicators are a subset of the key national indicators for child health, development and wellbeing. In 2006, the 19 priority areas of the Children’s Headline Indicators were endorsed by 3 ministerial councils. One ministerial council focused on health, another on education, and another on community and disability services. There is scope for a comprehensive review of these areas and the indicators to ensure they reflect contemporary information needs. Established child indicators have been supplemented by emerging topics identified in the course of data gaps analyses.

Each topic area in this report outlines the importance of the subject to child wellbeing, and present data on established measures over time, and for particular priority population groups, wherever possible. International comparisons are given where available. Limitations in current national reporting, and opportunities for development, are discussed, and sources for more information are given. For topics that do not have established measures, available national data sources or sub-national data sources have been used to give some insight on the topic.

A companion PDF report Australia's children: in brief, gives a high-level summary of key statistics and findings from the report.

Data tables were updated on 25 February 2022 for data sources for which more recent data were available. Both updated and the previously released data tables are available in the Data section. Written summaries for the Australia’s children web report remain as published in December 2019, with the exception of amendments summarised on the Notes page.

The importance of national reporting

Reporting on national data informs an understanding of how Australian children are faring over time, supports comparisons across different groups and internationally, and compares to support more local level reporting.

The purpose of Australia’s children is to:

- bring together and contextualise key national statistics on child wellbeing in 1 place

- give updated data on 38 measures, not elsewhere published under other AIHW child reporting frameworks

- support a more comprehensive understanding of related data gaps.

The report’s online format supports regular data updates and could, in future, present data at finer levels of disaggregation; for example, at small geographical area levels, to complement other reporting.

About this report

Children in scope for this report

Definitions for what constitutes the age range for children vary across Australian and international data collections and reporting. Definitions can be based on theories of child development and/or levels of dependency at different stages from birth to youth, or legal definitions.

For this report, children are defined as aged 0–12, covering infancy through to the end of primary school.

The importance of the antenatal period to childhood is acknowledged and included. This age range aligns with the Children’s Headline Indicators, and complements the age range in the National Youth Information Framework of 12–24 year olds (noting an overlap of children and young people aged 12). Where data for 0–12 year olds are not available or the numbers are too small for robust reporting, a different age range (most commonly 0–14 years) is reported. This is especially the case for health-related data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) and for this reason summary demographic information is also given for 0–14 years in Australian children and their families. It is recognised that the age span covered in this report may include early adolescence. For ease of reference the term ‘children’ will be used.

While childhood influences adolescence and young adulthood, specific subjects relating to youth wellbeing are beyond the scope of this report. The AIHW reports separately on youth to enable more thorough reporting on those factors influencing youth development and wellbeing (Figure 1). Data on youth reporting is currently included in Australia's youth (web report released in 2021) and the data portal National Youth Information Framework (last updated in 2015). Regardless of the scope for each measure, AIHW reporting on children and youth also present data by specific 5-year age groups wherever possible.

Figure 1: Relationship between AIHW reporting on children and youth

An ecological approach to reporting about children

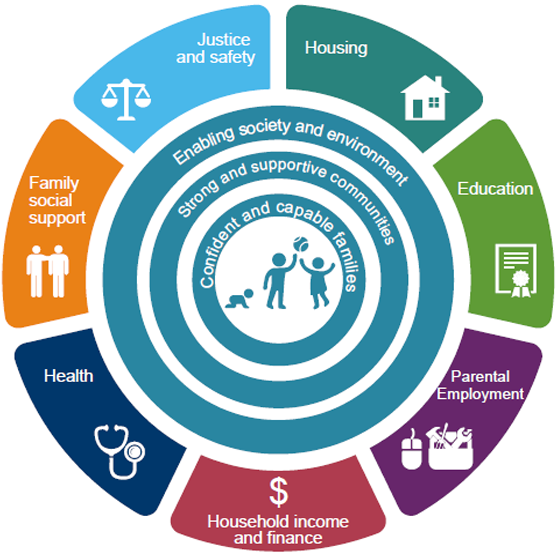

This report takes an ecological approach to child reporting, derived from existing frameworks used in Australia, which place child development at the centre (Victoria Department of Education and Training 2018; Tasmanian DHHS 2018). This approach recognises that positive child development occurs within dynamic concentric circles of influence exerted by different settings:

- immediate influences on the child of a confident and capable family

- direct and indirect influences of strong and supportive communities

- broader influences of the wider society in which the child lives.

The many influences on the child of these spheres can be organised into a information domains. The structure of this report draws on the 7 domains of the AIHW’s people-centred data model. This model is based on social–ecological models of the determinants of health and wellbeing and was developed to measure and report on health and welfare of the general population. It has been modified for child reporting and includes 7 information domains across the health and welfare sectors: individual health, education, family social support, household income and finance, parental employment, housing, and justice and safety. The impact of the interrelationship of the domains in the context of children’s development and wellbeing is highlighted in Figure 2.

Figure 2: AIHW people-centred data model and an ecological approach to child development

Priority population groups

The AIHW’s people-centred data model approach supports reporting on population groups that are especially vulnerable and often in greater need of health and welfare services and support. Many inequities that start early in childhood, persist into adulthood and can be passed on to the next generation (RACGP 2018).

For children, a number of priority population groups have been identified. These include children:

- from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander backgrounds

- from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, including children of refugee and asylum seeker families

- with disability

- who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and gender diverse, or children who have intersex variations

- living in out of home care

- who are incarcerated

- with parents in the youth justice system

- born into poverty

- experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage

- living in rural and remote communities (AHRC 2017; RACGP 2018).

To assist in identifying inequity, the report aims to present data for each domain disaggregated by children described in these priority population groups, wherever possible. However, due to current data availability, reporting has generally been limited to children:

- from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander backgrounds

- from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds or born overseas

- living in different geographical areas (remoteness)

- living in areas with different socioeconomic characteristics.

While some Indigenous Australians experience little or no disadvantage, other Indigenous Australians are highly disadvantaged (SCRGSP 2016). A significant amount of evidence suggests that disadvantage among Indigenous Australians has deeper underlying causes, including ‘intergenerational trauma’ resulting from the effects of:

- colonisation

- loss of land, language and culture

- forced removal of children

- racism

- discrimination (SCRGSP 2016; AIHW 2018).

Members of the Stolen Generations (people forcibly removed from their families as a result of government policies across Australian jurisdictions) are recognised as experiencing worse outcomes in a range of areas, including health, socioeconomic, justice and housing, compared with Indigenous people not removed from their families (AIHW 2018). Indigenous children living in households with members of the Stolen Generations are also more likely to experience adverse outcomes than other Indigenous children (AIHW 2019a). These historical factors are important for interpreting the data given about Indigenous children throughout this report.

While disadvantage among Indigenous children can vary by geography and other socioeconomic factors, reporting on these additional dimensions is beyond the scope of this report.

Data are included on children living in areas of low socioeconomic status for each section, using the Index of Relative Socio-Economic Disadvantage (see Technical notes). It should be noted that children experiencing economic disadvantage may also experience social exclusion.

This report includes some overarching information on children with disability, children living in out-of-home care, and children involved with the justice system; however, additional data on these groups from other sources is limited.

Reporting data for different groups is important for high-level national reporting; however as each sub-group is reported separately, insight on the multiple disadvantage that children may experience is not given. For example, children living in out-of-home care can also experience relatively high social and economic disadvantage (Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse 2017). A wide range of other factors, such as biological, developmental and environmental, can impact a child’s vulnerability and potential need for services and support.

National reporting on child wellbeing

Responsibility at the national level for services and/or policies to support core elements of child wellbeing-health, development, learning and safety-cuts across different sectors. It also cuts across different government departments:

- Health

- Social Services

- Education and Training

- Prime Minister and Cabinet, which since January 2019 includes the National Office for Child Safety.

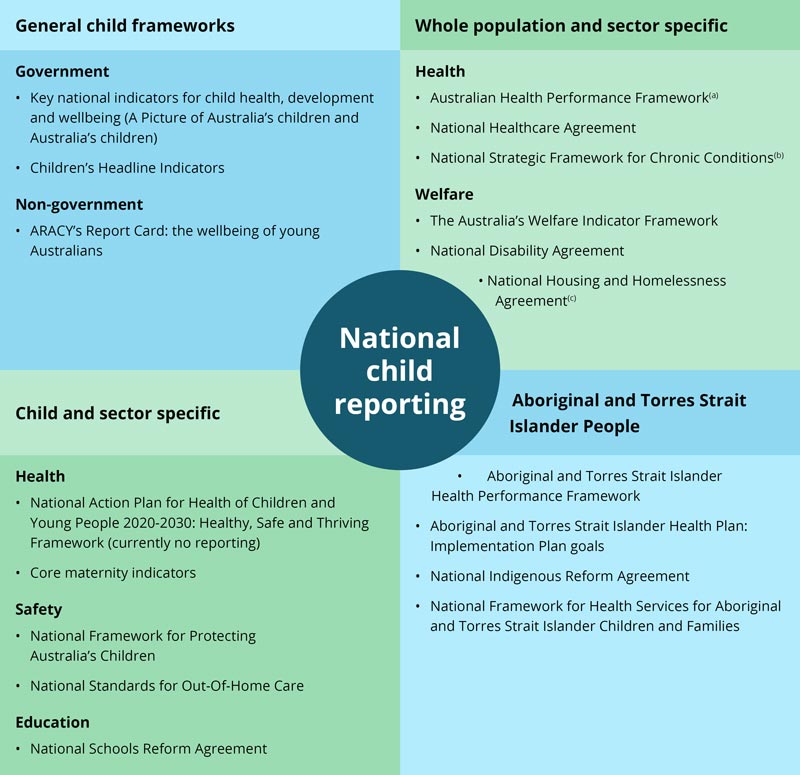

As a result of the shared responsibility for child health and wellbeing, national reporting frameworks have been developed by different government departments as well as non-government agencies to support decision making. Some reporting frameworks are child-specific and broad in scope while others focus on an aspect of child wellbeing (for example, child safety). Others cover whole-of-population, or specific population groups (for example, Indigenous children) and include indicators relevant to children and/or disaggregate for children.

Figure 3 categorises the reporting frameworks as:

- general child frameworks (holistic in nature)

- subject-specific child frameworks

- whole-of-population frameworks

- Indigenous frameworks.

For information on policies and/or strategies, and national royal commissions on specific subject areas, see the introduction of the relevant domain:

Figure 3: National frameworks that report on children

- The Australian Health Performance Framework subsumes The National Health Performance Framework and the Performance and Accountability Framework. A core set of indicators has been agreed.

- Indicators for the National Strategic Framework for Chronic Conditions are being finalised.

- Indicators for the National Housing and Homelessness Agreement and any disaggregation for children are being finalised.

Some variation exists across the frameworks in relation to the:

- breadth and depth of domain subjects covered

- age range reported

- disaggregation of data for specific populations

- frequency of reporting (Table 1).

| Framework | Age in years | Disaggregations | Reporting frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Key national indicators of child health, development and wellbeing (Australia’s children) |

0–12 |

Age, gender, Indigenous, CALD, Remoteness, SES, some international |

4-yearly to 2012 |

|

Children’s Headline Indicators |

0–12 |

State/territory AND age, gender, Indigenous, CALD, Remoteness, SES |

Annual to 2017 |

|

Key national indicators of youth health, and wellbeing (National Youth Information Framework indicators) |

12-24 |

Age, gender, Indigenous status, CALD, Remoteness, SES, some international |

4-yearly to 2015 |

|

ARACY Report Card |

0–24 |

Indigenous, International |

5-yearly |

|

National Framework for Protecting Australia’s children |

0–17 |

Age, gender, Indigenous, CALD (for some indicators) |

Annual |

|

National Standards for Out-of-Home Care |

0–17 |

TBC |

Annual |

|

National core maternity indicators |

Mothers and babies |

Indigenous, CALD, SES, Remoteness |

Annual |

|

Australian Health Performance Framework |

Whole population |

TBA |

2-yearly |

|

Australia's Welfare Indicator Framework |

Whole population |

Varying child ages |

2-yearly |

|

National intergovernmental agreements |

Whole population/students |

Varying child ages |

Annual |

|

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework |

Whole population |

Varying child ages |

2-yearly |

|

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan: Implementation Plan goals |

Whole population |

Varying child ages |

Annual |

Abbreviations: ARACY (Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth); CALD (Culturally and linguistically diverse); SES (Socio-economic status).

Variation also exists in the topics covered in each domain of the frameworks (not included here) which reflects their different purposes.

Of the 7 domains in the AIHW people-centred data model, the Health domain has the highest number of established measures across the various frameworks while the Household income and finance, and Parental employment domains have the fewest (Table 2).

The maturity of indicators available for reporting also impacts the breadth of topics covered in each domain in this report. Well-established indicators are used to describe most existing topics in the domains of Health, Education, and Household income and finance. Relatively less-established indicators are used to describe several topics in Family social support, and Justice and safety, especially for children outside the child protection population.

While there is growing interest in Australia and internationally in developing positive indicators for child wellbeing, some national well-established indicators presented in this report have a deficit, rather than strengths-based focus.

| Framework | Health | Family social support | Justice and safety | Housing | Education and skills | Income and finance | Parental employment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Key national indicators of child health, development and wellbeing (Australia’s children) |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

|

Children’s Headline Indicators |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

|

Key national indicators of youth health, and wellbeing (National Youth Information Framework indicators) |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

ARACY Report Card |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

National Framework for Protecting Australia’s children |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

|

National Standards for Out-of-Home Care |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

||||

|

National core maternity indicators |

✔ |

|

|||||

|

Australian Health Performance Framework |

✔ |

||||||

|

Australia's Welfare Indicator Framework |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

|

National intergovernmental agreements |

NHA NDA NIRA |

NHHA |

NSRA |

||||

|

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

||

|

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan: Implementation Plan goals |

✔ |

Abbreviations: ARACY (Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth); NHHA (National Housing and Homelessness Agreement); NSRA (National Schools Reform Agreement); NYIF (National Youth Information Framework).

Children’s perspective of wellbeing

How children view their own wellbeing (subjective, or self-reported wellbeing) is important (Box 1).

Box 1: Measuring wellbeing

Wellbeing is defined as a state of health, happiness and contentment (AIHW 2018). What this actually includes has been widely contested over the years; however, recent years have seen growing support for a comprehensive view of wellbeing that includes components of both objective and subjective wellbeing (Wallace et al. 2011).

Objective wellbeing includes indicators of how well people are, or are doing, measured by national health statistics (physical and mental) and socio-economic indicators; for example household income or unemployment level (AIHW 2018; Pollard & Lee 2003).

Subjective wellbeing, on the other hand, uses self-report instruments to gather information about how well people think they are doing in all health and socio-economic aspects of their life (AIHW 2018; Deci & Ryan 2008; Pollard & Lee 2003). Subjective wellbeing is usually measured with surveys that can target 1 specific aspect of life (for example, mental health or education) or, more broadly, a person’s overall life satisfaction and/or happiness (Dolan & Metcalfe 2012; Wallace et al. 2011; Stiglitz et al. 2009).

Currently, national data related to the wellbeing of children are primarily administrative and based on service delivery by-product information (that is, not self-reported by the child), or surveys administered only to adults (for example, the National Health Survey). However, several published reports give data on wellbeing from the child’s perspective. These include reports published by the:

- national and jurisdictional children’s commissioners and guardians

- Australian Child Wellbeing project

- AIHW-survey on children’s experiences of out-of-home care experiences (AIHW 2019b)

- Longitudinal Study of Australian Children-data has recently been used to measure child deprivation and opportunity across a number of domains relevant to child wellbeing (Sollis 2019).

In recent years, Behind the News has also run 2 large-scale self-selected Kids’ Happiness surveys looking at the subjective mental health and wellbeing of Australian children aged 6–18 (Box 2).

Box 2: How do Australian children rate their own wellbeing?

Approximately 47,000 Australian children aged 6–18 self-selected and completed the 2nd Behind the News Kids’ Happiness Survey—93% (approximately 43,700) were aged 6–12. Some key findings for children aged 6–12 include:

- 3 out of 5 (63%) felt happy lots of the time. The things most likely to make them happy include friends (64%), family (60%), playing sport (53%) and music (50%).

- 3 out of 4 (76%) felt scared or worried at least some of the time. The things most likely to cause worry, include the future (73%), issues with friends (68%), issues with family (69%) and their health (69%).

- 71% said they talk to their parents if they have a problem and 50% said they talk to their friends.

- 1 in 4 (25%) children reported they did not talk to anyone if they have a problem.

- some children reported they did not feel safe at home (9%), at school (14%) or in their neighbourhood (24%) a lot of the time.

- 1 out of 4 (28%) reported that their device (phone, tablet, computer or video console) was stopping them from getting the right amount of sleep at least some of the time.

Source: University of Melbourne analysis of the second Australian Broadcasting Corporation Behind the News Happiness survey data.

Indigenous people define their personal health and wellbeing beyond physical health and social and emotional aspects to include spiritual and/or cultural aspects and the need for a connection to environment, community and family (Bourke et al. 2018; Boddington & Räisänen 2009; Brady et al. 1997). Culture and cultural identity are crucial components (Box 3). A number of historical factors can also impact the wellbeing of Indigenous children, including intergenerational disadvantage, the impact of the Stolen Generation and Indigenous community functioning (AIHW 2019a; AHMAC 2017).

Limited national data sources are available on the subjective wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in Australia. The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children has collected some data on subjective wellbeing, including their feelings, social supports and the activities they enjoy (DSS 2015).

Box 3: Cultural identity

Children are not born with a sense of cultural identity but rather develop it through exposure to traditional and cultural knowledge, language, practices and activities (Kickett-Tucker et al. 2015; PM&C 2017; DoCA Arts 2019). In most instances, families and broader kinship groups are likely the primary source for providing and supporting these exposures for Indigenous children in Australia (Lohoar et al. 2014).

The 2014–15 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey captured information relevant to aspects of cultural identity for Indigenous children aged 0–14 in selected households by way of a proxy interview with a parent or other adult household member (ABS 2016). The 2014–15 survey results estimated that of the approximately 173,000 Indigenous children aged 4–14 years:

- 50% (approximately 86,900) identified with a clan, tribal or language group. This increased to 71% when only looking at children living remotely.

- Just less than 8% (approximately 13,000) spoke an Australian Indigenous language as their primary language at home. This increased to 31% for children living remotely.

- 34% (approximately 58,400) spoke at least a few Australian Indigenous words. This increased to 66% for children living remotely.

- 75% (approximately 129,800) were involved in selected events, ceremonies or organisations in the last 12 months. This increased to 80% for children living remotely.

- 44% (approximately 75,900) spent at least some time with a leader or elder each week. This increased to 66% for children living remotely.

Data supporting national indicator reporting

As Australia’s children aims to give a national overview of how Australian children are faring at a particular point, which can be regularly updated and progress tracked, the report focuses on data which are nationally representative, collected periodically, and which support population-level comparisons.

The report draws predominantly on:

- cross-sectional administrative datasets held by the AIHW

- national surveys by the ABS

- specific national collections such as the Australian Early Development Census and National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy.

See the Data Sources for a full listing of data sources used. However, for some topics of interest, other national data sources that may not meet the above criteria, or sub-national data-sources, have been used for insight on a topic (also Box 4).

In future, data integration could provide opportunities for improved national indicator reporting; for example, by bringing together data from multiple sources relating to select population groups (such as children in out-of-home care) to better understand their use of services across multiple sectors (such as education, health and justice) and their transitions over time (such as from school to work).

Box 4: Additional studies and data sources on children

The rich national data sources described briefly here can demonstrate how children respond to different situations over time, and assist in identifying pathways for children, or paint a very rich picture of child wellbeing.

Longitudinal Study of Australian Children and Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children

These studies each follow 2 cohorts of children as they grow up. Data from these studies can show why children have taken particular pathways and what factors have made a difference to their outcomes over time, especially when linked to administrative data sources such as Medicare, National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy and Australian Early Development Census:

- The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children collects information on physical and mental health, education, and social, cognitive and emotional development of 2 large cohorts of children (totalling >10,000 children at the outset of the study in 2004). The 2 cohorts are made up of children born March 1999 to February 2000 and March 2003 to February 2004. The data are sourced from parents, child carers, pre-school and school teachers, and the children themselves.

- The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children collects information on physical and mental health, education and social, cognitive and emotional development, as well as families, communities and services of 2 cohorts of Indigenous children (totalling around 1,700 children at the outset of the study in 2008). The 2 cohorts are made up of children born December 2003 to November 2004 and December 2006 to November 2007. The data are sourced from parents, child carers, pre-school and school teachers, and the children themselves.

Australian Child Wellbeing Project

Published in 2016, this project focused on children in the middle years (aged 8–14). It used the perspectives of young people to conceptualise and measure wellbeing. Marginalised groups were a particular focus and included: young people with disability, young carers, materially disadvantaged, CALD, Indigenous, rural and remote, young people in out-of-home care.

Royal Children’s Hospital National Child Health Poll

This poll is a quarterly, national survey of Australian households providing information on important issues in contemporary child and adolescent health, as told by the Australian public (specifically from the point of view of the parent). Each quarter, the poll focuses on a different topic or theme. The process for selecting poll topics responds to and is informed by the national political and social agenda. For more information, see poll survey methods.

International reporting on child wellbeing

Australia is a signatory to the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of the Child which underpins the work of the National Children’s Commissioner, a role established in 2012. The Commissioner produces an annual Statutory Report to Parliament focusing on recurrent child wellbeing themes in contemporary Australia, including safety, social support and health issues (Children’s Rights Report).

Every 5 years, the Children’s Commissioner reports to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child about Australia’s progress in implementing the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. In January 2018, the Australian Government submitted Australia's combined 5th and 6th periodic reports on progress under the Committee on the Rights of the Child and its Optional Protocols to the UN.

In February 2019, the National Children's Commissioner addressed the UN Committee and assisted them in looking at the major issues facing children living in Australia. Following this, the UN Committee gave the Australian Government a list of issues to be addressed in writing and provided Australia with its Concluding observations and recommendations.

Where do I go for more information?

For more information on:

- children’s rights and reporting to the UN, see: Children's rights

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2016. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey, 2014–15. ABS cat. no. 4714.0. Canberra: ABS.

AHMAC (Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council) 2017. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework 2017 report. Canberra: AHMAC.

AHRC (Australian Human Rights Commission) 2017. Children’s Rights Report 2017. National Children’s Commissioner. Sydney: AHRC.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2016. Australia’s health 2016. Australia’s health series no. 15. Cat. no. AUS 199. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2018. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Stolen Generations and descendants: numbers, demographic characteristics and selected outcomes. Cat. no. IHW 195. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2019a. Children living in households with members of the Stolen Generations. Cat. no. IHW 214. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2019b. The views of children and young people in out-of-home care: overview of indicator results from the second national survey 2018. Cat. no. CWS 68. Canberra: AIHW.

Boddington P & Räisänen U 2009. Theoretical and practical issues in the definition of health: insights from Aboriginal Australia. Journal of Medicine and Philosophy 34:49–67.

Bourke S, Wright A, Guthrie J, Russell L, Dunbar T & Lovett R. 2018. Evidence review of Indigenous culture for health and wellbeing. The International Journal of Health, Wellness and Society 8(4):11–27.

Brady M, Kunitz S & Nash D. 1997. Who’s Definition? Australian Aborigines, conceptualisations of health and the World Health Organization. Ethnicity and Health: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives, edited by Michael Worboys and Lara Marks, pp. 272–90. London: Routledge.

Deci EL & Ryan RM 2008. Hedonia, eudaimonia, and well-being: an introduction. Journal of Happiness Studies 9(1):1–11.

DoCA (Department of Communications and the Arts) 2019. Australian Government Action Plan for the 2019 international year of Indigenous languages. Canberra: DoCA. Viewed 19 August 2019.

DSS (Department of Social Services) 2015. Footprints in time: the Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children—report from Wave 5. Canberra: DSS.

Dolan P & Metcalfe R 2012. Measuring subjective wellbeing: recommendations on measures for use by national governments. Journal of Social Policy 41(2):409–427.

Kickett-Tucker CS, Christensen D, Lawrence D, Zubrick SR, Johnson DJ & Stanley F 2015. Development and validation of the Australian Aboriginal racial identity and self-esteem survey for 8–12 year old children (IRISE_C). International Journal for Equity in Health 14:103.

Lohoar S, Butera N & Kennedy E 2014. Strengths of Australian Aboriginal cultural practices in family life and child rearing. Child Family Community Australia Paper No. 25. Melbourne: AIFS.

Pollard EL & Lee PD 2003. Child well-being: a systematic review of the literature. Social Indicators Research 61(1):59–78.

PM&C (Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet) 2017. Closing the Gap Prime Minister’s Report 2017.

RACGP (Royal Australian College of General Practitioners) 2018. Inequities in child health: position statement. Sydney: RACGP.

Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse 2017. Final report: Royal Commission into institutional responses to child sexual abuse, preface and executive summary. Sydney: Government of Australia. Viewed 13 May 2019

SCRGSP (Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision) 2016. Overcoming Indigenous disadvantage: key indicators 2016. Productivity Commission: Canberra.

Sollis K 2019. Measuring child deprivation and opportunity in Australia: applying the nest framework to develop a measure of deprivation and opportunity for children using the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. Canberra: Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth.

Stiglitz JE, Sen AK & Fitoussi JP 2009. Report by the commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress. Paris: Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress.

DHHS (Tasmanian Department of Health and Human Services) 2018. Tasmanian Child and Youth Wellbeing Framework. DHHS.

Usborne E & Taylor D 2010. The role of cultural identity clarity for self-concept clarity, self-esteem, and subjective well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 36(7):883–97.

Victoria Department of Education and Training 2018. Victorian Child and Adolescent Monitoring System Outcomes Framework. Viewed 14 August 2019.

Wallace A, Holloway L, Woods R & Malloy L 2011. Literature review on meeting the psychological and emotional needs of children and young people: models of effective practice in educational settings, Urbis, prepared for the New South Wales Department of Education and Communities.

The Index of Relative Socio-Economic Disadvantage reflects the overall or average level of socioeconomic disadvantage of the population of an area; it does not show how individuals living in the same area differ from each other in these socioeconomic factors (AIHW 2016).